イタリア庶民料理のオーラルヒストリー①Nonna Lucia: Altamuraの農民料理(インタビューノート)

卒論「Peasants in the kitchen: Oral History of Italian Peasants' Cooking」

オーラルヒストリーのインタビュー内容のまとめ。

インタビュー①Nonna Lucia, Altamura, Puglia

Basic Information about interview

Date: 23.12.2022 and 28.12.2022

Place: Home (Altamura, BR, Puglia)

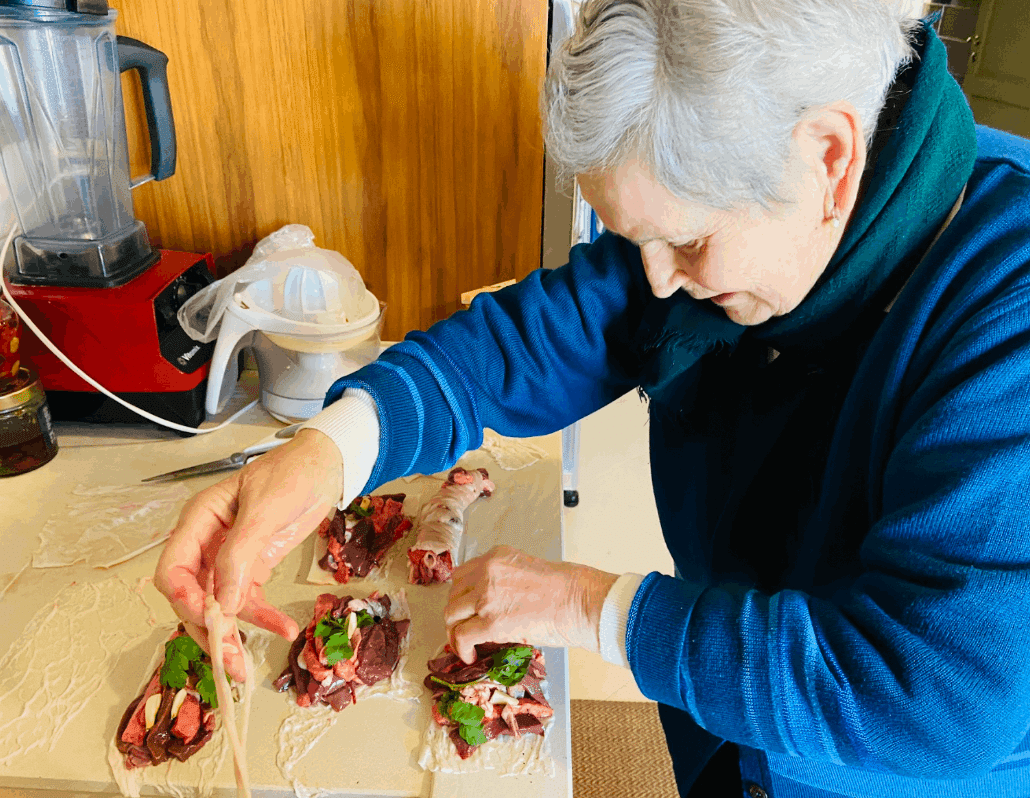

Style: Dialogue on the table with photos and dialogue while cooking and eating

Profile:

Lucia Carone (Nonna Lucia)

Lucia Carone was born on November 19 in 1939 in Altamura as the first child between Laura and Donato Carone. Later, she got a brother called Mattia, three years younger than her and a sister called Marianna, eight years younger than her. The family made a living by agriculture in Murgia, farming wine grapes, olive, grain and oat. Since she was 5 years old, she went to the farm to help her parents. She went to school but quit because she was too busy helping the family farm especially during the summer period.

She got married in 1965 at the age of 26 with Francesco Volse, a son of the peasant family in Gravina. The husband worked in Germany as a construction worker for six years from 1962 to 1968. After he came back, they started to live together at the current house and had three children. They made a living by agriculture in the family field. She helped her husband with farming while she did household chores including raising three children.

Relationship with author:

The author knows Nonna Lucia because she was the mother of her host mother in Altamura. She has known the family since 2018, being taken care of by them like a real daughter.

Oral History of her life

- About life as a peasant

Q. How did you work as a peasant?

I had helped my parents with farming since I was five. I was always in the farmland with my family. My younger sister was two when she started to come to farmland. The busiest season was between Easter (March or April, depending on the year) and Ferragosto (August 15). The day after Easter, we didn’t celebrate Pasquetta but immediately started to work as we didn’t want to waste the time. During this season, we woke up at 4 in the morning and left home in the darkness. We went to our farmland in a small horse cart. It took around 30 minutes from our house to farmland. We children were sleeping in the cart while my father was guiding the horse. Soon after we arrived in the farmland, we started to work.

Around 9 in the morning, depending on the day and how much we proceeded, we took a small break, eating bread and salami for breakfast. Around noon to one, we ate lunch and also around 5, we took a small break again with bread and salami. We worked until around 8 when it got dark and came back home in the horse cart. We were really tired. It was the most intensive moment of the year of harvesting.

Around Ferragosto, we harvested oats using our horse. We brought oats downstairs of the house while we put horse’s straw upstairs. From September to November, we seeded grain with the horse. I remembered that my father moved forward with the horse on the farmland to make a line, and we children and my mother followed it and threw the seeds on the line on the line. Also we needed to harvest olive and wine grapes during this period. We harvested around 5000 kg of olives and 20000 kg of wine grapes every year.

In December, we didn’t have many things on the farm so we took a little rest. During this period, we worked on the house, clothes and so on. Also in January and February too, we mostly did work at home while male family members sometimes went to farmland to maintain it.

Q. How did you live in the house?

We lived in a very small house, which had only one room where parents slept on one side and children slept on the other. Downstairs, there was a space for horse to sleep and harvested products to be conserved. Also there was a little space as a kitchen where my mother was making pasta with me and my sister. There was an instrument for squeezing grapes too. My father was doing this work in the season of harvesting grapes.

As for the animals, we had horses, which was used for bringing us and tools between home and farmland and for farming the land as I mentioned above. We also had hens and rabbits. For a special occasion, we ate those animals.

We also had a house in the farmland, which was made of stone. It was mainly for storing the farming tools. It also served as a shelter when it rained heavily.

- About cooking

Q. How did the family cook and eat?

My mother cooked everyday in the evening. She made fresh pasta everyday. The pasta was always made from our durum wheat without egg but only with water. She made it everyday because we didn’t have a fridge at that time so we couldn’t store the pasta for more than two days. She made just for what we needed without any leftovers everyday. For condiment, we used what we had and found everyday. We found wild vegetables and herbs in Murgia, so we used them a lot. Today we will cook ‘cavatelli con cardoncelli e finocchietto all’olio fritto,’ which we were mostly eating as an everyday dish.

In our daily life during the summer period, we brought bread and salami when we left home. At 9 in the morning, we ate bread and salami in the farmland. For lunch, sometimes my father made fire with wood and my mom cooked lunch on the fire with the pan he brought from home. In this case, she cooked pasta al sugo (simple tomato sauce pasta) with dry pasta bought at the shop. The tomato sauce was made every summer and stored so that we could use one for the whole year. We put the cloth on the ground and ate lunch. Then around 5, we ate bread and salami again as we were hungry and still needed to work. Working as a peasant needs a lot of energy. When we got home from the farmland around 9 at night, my mother made the pasta and we ate it all. Soon after we finished eating, we went to bed. Why did she make pasta everyday though dry pasta could have been bought? Because fresh pasta is more delicious. Also because we can use our durum wheat we harvested.

We didn’t have individual plates as we have today. So we used a big plate where my mother put the food she cooked and everyone ate from that plate. Our family’s plate was like this, but for example, my husband’s family used a bigger one.

My mother baked bread once a week. The bread, now famous as ‘Pane di Altamura,’ was 5 kg for each. She made three for our family every week. The number of the bread depended on the size of the family. We were five so three breads were enough for us for one week. It was hard work to knead a dough for such a big quantity. It was like this, it needs power because obviously we didn’t have a machine so did everything by hand. We used the public oven to bake it. We could use the oven only once a week for each family, so we needed to bake that much at one time. Usually they put the stamp of the family mark on the bread so that they could recognize which one is their family, but in my mother’s case, she didn’t use it because she was too good at kneading the dough, so she could recognize hers without the stamp. She was great at baking bread. Not only baking, but she was very good at cooking overall, sewing, praying and so on.

I improved my cooking from my mother. When she was making the fresh pasta downstairs, my sister and I were making it together. Even though she didn’t have any recipe, my mother was very precise. While I was forming the pasta next to her, if I made it a little bigger or smaller, or in a form a bit different from hers, she almost hit me and made me redo it. Cavatelli and cavatellini should be this size each and tagliatelle should have this length and width.

Usually we had enough food thanks to god and hard work, but sometimes we lacked food. When we didn’t have enough bread we used the grain that my father had hidden between grape trees. We grinded the grain by hand and used it for dishes.

Apart from the everyday cooking, for special occasions we cooked some different dishes. For example, we usually didn’t have meat but ate it for Christmas. It was really rare. We made brodo with the meat and on the 26th we ate ‘verza in brodo di carne (meat-stock soup with cabbage)’ sprinkling the crumbled meat used to make a soup stock. Also in this case, we didn’t throw away anything, making use of all the ingredients we had. For the 24th, we prepared vegetable dishes, sometimes with baccalà, which was the least expensive fish, depending on the year. Another example of food for special occasions is ‘gnummareddi.’ They are rolls of intestines of lambs. They were eaten in the occasion of wedding, First Communione day, Christmas and Easter.

Thanks to Gesus, I don’t have a food preference. I can eat anything. I am very grateful for this .Since we lived in a time when food was not abundant, I know how to make use of what we have and I don’t throw away anything. I even make aprons using the cloth of old shirts.

- Later period

Even after I got married, I didn’t change my way of cooking. Of course, my husband had eaten different things that his mother prepared but not too different. I didn’t adapt to his food but continued to cook how my mother had cooked.

However as for the lifestyle, it changed a lot. After I got married, I helped my husband’s farm but mostly only for harvesting olives. I had to do many things at home including raising three children.

Then in the 1960’s and 70’s, we experienced rapid economic growth and since then, it changed a lot because we’ve got electric devices such as a fridge. And we came to buy more ingredients at the supermarkets including pasta. For example, now I make fresh pasta only once a week for Sunday.

- Others

Q. Did you have any chance to see other people’s cooking like eating at your friends’ house?

No. We played a lot together, we talked almost everyday when we saw each other, but I never ate lunch nor dinner at my friend’s place. The only home I went to to eat was my aunt’s. She was a sister of my mother and lived nearby. Sometimes, we ate there but never at our place since their house was bigger and our house didn’t have enough capacity.

—-

Dish description

Cavatelli con cardoncelli e finocchietto all’olio fritto

1 Make pasta with semola & semola rimacinata

2 Wash cardoncelli*1 e finocchietto and boild them for around 40 minuti

3 Remove the verdure and in the same water boil pasta

4 In the pan, stir-fry garlic with olive oil per fare ‘Olio fritto*2

5 Sbriciolare old bread in the oil*3

6 Put pasta, vegetables and oil on the plate and mix them well on the plate

*1 It’s a local vegetable, spontaneously growing in Murgia. The name is the same as funghi cardoncelli but different

*2 She uses ‘olio fritto’ for olive oil with garlic, ‘olio crudo’ is olive oil without garlic

*3 Substitution for cheese

My comments and question

<About the case of Nonna Lucia>

・‘Because it is delicious.’ is culture?

I was impressed when I asked her ‘Why did her mother make fresh pasta everyday?’ she answered immediately as if it were too obvious ‘Perchè è buona (Because it’s delicious)’. This simplest answer makes me think the essence of culture is. Even though she came home very tired after the long day in the farmland, she still made pasta for her family in spite that she could have bought dry pasta at a shop. This motivation of eating good food in the family might be something deeply rooted in the culture. For example, if it were in another culture, she might not have made it but might have bought it.

・How has economic growth in the 1960’s and 70’s impacted on peasants’ cuisine?

What changed the cooking of Nonna Lucia seems to be the economic growth in the 1960’s and 70’s. In many cases including my grandmother’s case, the biggest turning point of her cooking was marriage with my grandfather. She needed to learn new cooking from the mother of her husband to make it more preferable for her husband. My mother too. I was interested in this point as elements of change of home cooking.

<About methodology>

・Many want to talk about their personal cooking history

This is good news for the research of oral culinary history. I didn’t expect this, but so far, they were very happy to talk about their personal cooking no matter how poor and difficult it was. Nonna Lucia remembered her childhood days very well and continuously talked though usually she is not talkative. Also other women with whom I made an appointment were happy/looking forward to talking about her life.

・Language problem

Nonna Lucia is more comfortable talking in her dialect, which I don’t understand at all. Maybe it’s better if we could use the language that the interviewee is most comfortable with..?

・The number of the cases

In the original proposal, I was supposed to do the interview for three peasants’ women in different regions. Should I conduct more interviews? If so, is it better in the same regions or in various regions? Could you help me find interviewees..?

イタリア庶民料理の研究プロジェクトについて

歴史上「声なき」庶民の料理を研究するプロジェクト、サポーターを募集しています。

研究会にて伴走型で研究を深めたり、応援頂ける方、ぜひ宜しくお願い致します!

ここから先は

ボローニャ大学修士、料理史学徒の研究ノート

ボローニャ大学修士、歴史文化学「Global Cultures: Food History」専攻の学生が、研究内容を共有するマガジン ・…

Amazonギフトカード5,000円分が当たる

この記事が気に入ったらチップで応援してみませんか?