The Dream of Toshiko Akiyoshi's Craziest Fan

I looked up, the whole ceiling was covered in concert posters.

“They are all of the same person, Toshiko Akiyoshi,” said Terui-san, the owner of Cafe Johnny in Kaiunbashi.

Twilight (1976), Terui-san played Spiritual Nature (1975).

On the wall, I saw a CD with The Heart Sutra and techno written on the cover,

I felt an affinity as my name was taken from The Heart Sutra.

I came across the cafe of “the world’s craziest fan” of the 92-year-old legendary jazz pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi, which she acknowledges. Terui-san, a dedicated listener of Akiyoshi-san’s music since 1974, his dream to establish a jazz museum for Toshiko Akiyoshi will soon come true. The jazz museum will be located on the third floor of Hotel Mazarium at the Morioka bus terminal. People passing by can discover her lifelong journey, which conveys a message – with hard work, anybody can blossom. On November 11th, Akiyoshi-san will perform with her daughter, Monday Michiru, and her grandchild Nikita Sipiagin – the world’s first three-generation trio.

“If you improve a little bit more, there are still things left to do. I got here as an extension of that. It continues from here”.

Terui-san’s doorway to Akiyoshi-san’s music dates back to the Monthly Record Concert held for seven years. In 1980, during the last session, Terui-san’s sempai (senior) asked him to put on the Kogun (1974), which made his body shiver. The more he listened to her records, the more impressive they were. In the beginning, Terui-san intended to delve a little bit into the history of her music, and that “little bit” has turned out to be nearly half a century.

“For jazz, the rhythm comes from black people, and the melody on top comes from Europe. Where’s the Japanese element? There’s nothing in it. I thought it was my job to include something unknown, and Kogun was born. It’s a milestone.”

Born in 1929, when Japanese colonialism ruled Manchuria, present-day Liaoning, China, Akiyoshi-san began learning classical piano when she was seven. After the end of World War II, she was repatriated to her father’s hometown in Beppu, Oita Prefecture. Soon after, at 16, she yearned to play the piano, which led to an opportunity to work at the dance hall. In the summer of 1948, she moved to Tokyo and became fully absorbed in jazz.

In November 1953, Oscar Peterson's Trio performance for Jazz At The Philharmonic (JATP), held at Nichigeki Theatre, was a profoundly impactful experience for Akiyoshi-san. The following night, Peterson ran into her concert in Nishi Ginza and was highly impressed. Soon after, he recommended Akiyoshi-san to the influential producer of JATP, Norman Granz, which led to an immediate recording at the broadcast station. Akiyoshi-san’s 10-inch album was released in the U.S. the following year, which has garnered attention. Consequently, in 1956, Akiyoshi-san was invited to attend the Berklee School of Music on a full scholarship as its first Japanese student. Years later, she wrote the iconic Long Yellow Road (1975) as a Japanese woman in jazz, “There is still a long way to go.”

*In 1970, Berklee School of Music celebrated its 25th anniversary by changing its name to Berklee College of Music.

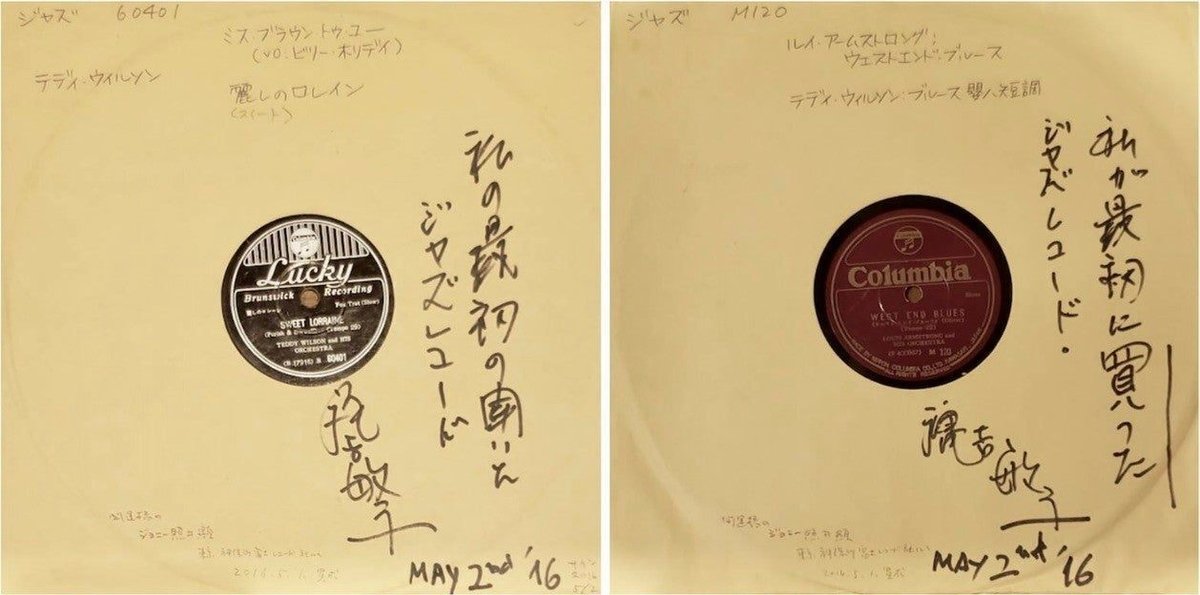

Terui-san crossed out the wrong date on the record and wrote the

correct date because he knows everything about her.

“The most important thing is when, where, who, and what.”

“Yes!” I responded, while engraving it into my notebook.

“For example, today, in Morioka and Me.”

“Toshiko-san’s study session!”

“That’s right!”

Akiyoshi-san’s jazz is deeply rooted in the Japanese way of thinking and culture; she reads avidly, such as The Book of Five Rings (1645) by Japanese swordsman Miyamoto Musashi and The Flowering Spirit, a 15th-century classic text by Zeami, founder of the Noh theatre. It is her way of shinken shōbu (serious competition and give it your all). Her prominent albums imbue Japanese elements are Oirantan (Tales of a Courtesan), based on the story of the Yoshiwara red-light district in the Edo period; Minamata from Insights (1976), drawn from the Minamata Disease caused by industrial wastewater from a chemical factory in the 1950s. Akiyoshi-san’s music taught Terui-san a certain way of life and became a source of energy for him.

“To do something that other people are not doing, I don’t think it would have happened if I didn’t listen to Akiyoshi-san’s music,” said Terui-san. Through his search in Japan, he discovered an absence of jazz kissas that specialise in Japanese jazz. As he turned 30, he was determined to make “Long Yellow Road” the theme of Cafe Johnny, hoping that talented Japanese musicians rise to the frontline of the music world.

“I have to do something about Japanese jazz that does not get any sunlight, the passion is boiling.”

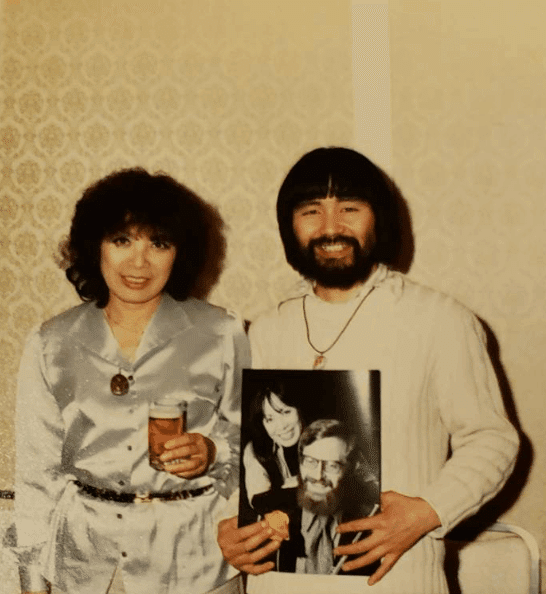

The year 1980 marked a turning point. Terui-san heard that Akiyoshi-san was performing at Akita and Aomori, and he took the one-day chance available. With his friends at the Sanriku jazz club, they invited her to perform at Rikuzentakada, Fukushima, where they met for the first time. Since then, every time she returns to Japan, she stops at Iwate. Terui-san moved to Morioka before the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake. However, tragically, the records he had accumulated from age 16 to 50, were all washed away by the tsunami. His past was obliterated. At that time, Akiyoshi-san gifted him with a live performance. Their magical relationship of 90% fan and 10% friendship was formed through music. Several times, he organised “Go to New York with Johnny” trips to attend Akiyoshi-san’s concerts, where he gathered almost 20 people to accompany him. Everyone was invited to Akiyoshi-san’s house in Central Park West and were treated to home-cooked meals.

“You go to New York quite often, who looks after your shop when

you’re gone?”, I asked.

“It’s closed. No income.”

On my second visit, Terui-san had just returned from New York. The vital mission was to bring back Akiyoshi-san’s precious Steinway piano from 1907, which she is gifting to the museum. The grand piano has a historical significance; she obtained it from the respected British pianist and music journalist Leonard Feather, and it has been played by prominent jazz musicians throughout the years. Five people from Japan went to bring back the piano from her basement, but it remains an arduous task. When Terui-san was talking about the failure with great laughter, the piano team leader, who has refurbished the pianos of the Japanese royal family, called. “I’m swallowed up by despair”, he said. Laughter erupted in the cafe again. Terui-san swiftly decided to change the strategy and try again. He firmly believes that “this piano will not only be a treasure for Iwate, but for Japan”, and he shows no signs of giving up.

The music hunt carries on in New York’s second-hand book shops. Although Terui-san cannot read English, he is highly conscious of dates. While flipping through an American music magazine devoted to “Jazz, Blues and Beyond”, Downbeat 1954, he instinctively looked for the text “Toshiko”, and the moment he discovered the tiny text, his heart almost stopped.

“Look, look, she wrote it!” Terui-san read the part underlined with a pencil out loud. Then, he started sniffing the air.

From Akiyoshi-san’s book Living with Jazz, he obtained the first record that she listened to and the first record she bought. He took out the records from his most vital folder and played Teddy Wilson’s 78rmp Sweet Lorraine (1935) and Louis Armstrong’s West End Blues (1928) from his gramophone. After relentless searches, he finally discovered them in Jimbocho, just a day before her performance in 2016. He was so proud and got it signed by Akiyoshi-san. When he found them, he pranced through the streets like he had won the lottery. Terui-san’s wife, Koharu-san, said, “I was drinking coffee and waiting for him at a kissaten (coffee shop), and he forgot completely about me. I could see him through the windows holding two records. He just walked past me!”

Terui-san is blessed by other fans. When Akiyoshi-san made a TV appearance, “Akiyoshi-san is on NHK!” he received a phone call from Kawamura-san, followed by another call from Sakamoto-san. They knew he would be thrilled to hear the news. When Tomita-san found the Asahi Sonorama Record Book (1961) and Akiyoshi Recital written on the Flexi disc, he gave it to Terui-san and said, “You deserve it more!”

Toward the end, Koharu-san became more enthusiastic than Terui-san. The most touching moment was when the Akiyoshi Orchestra played the critically acclaimed Hiroshima Rising composition at their farewell concert at Carnegie Hall on October 17th, 2003. It was so courageous of her, and Koharu-san cried and watched it with complex emotions. After that, every concert ended with the song Hope, according to Akiyoshi-san, “human beings cannot lose hope at any time.”

“It’s impossible to keep track of every single line of her past, but I am trying to pile up all of the information and spread it to the next generation.”

You cannot enjoy jazz without a formidable study from the performer and the listener. When you have a spectacular musician, there comes an extraordinary listener. Akiyoshi-san has broken the “glass ceiling” in jazz, and Terui-san poured his soul into her music. He feels that to know one thing, you need to know everything, such as the background of the music and what was happening in the country then. If you like something from your bones, you will persist through all difficulties. Terui-san sniffs out the clues and finds the connections between the dots, solving the mystery. When I walked out of Cafe Johnny that day, I had a strong feeling that I had discovered the key to what I was doing.

Terui-san still struggles to bring the piano back from New York. What amazed me is that he is creating a space for people to study jazz freely; however, he carries an enormous financial burden on his shoulders. Although the clock is ticking, I hope through writing this, I can spread the word to one more person – to think about how to bring the Steinway piano back.

“The darkness is deepest just before the dawn.”

Later on, I received an envelope from him. There was Akiyoshi-san's book and a few newspapers along with the square piece of paper I had asked him to ‘draw sound’ on. I was shocked to see my name in the Morioka Times newspaper. I had interviewed him, but he had interviewed me back without me realising, the astonishment that he had published the article before I did is still resonating in my mind.