江戸の台所を支えた漁師たちの沖飯「飛魚のなめろう/飛魚のさんが焼き」 "Flying fish namero" and "flying fish sangayaki" are okimeshi(dishes on the ship) of fishermen that supported the Edo kitchens.

作って辿る食文化史

Making and tracing the history of food culture

ストーリー

Recipe trivia

鎌倉の飲み客は総じて大人しい。

鎌倉幕府が無くなり久しく寒村だった鎌倉は、明治期に保養地として開かれ、後には東京に通う勤め人のベッドタウンになった。別荘住まいのパトロンを頼って集まった文化人は去ってしまい、大船の松竹撮影所も無くなってしまったけど、風致地区のお陰もあり、落ち着いた保養地の雰囲気が今でも残っている。そんな風土を気に入ってか、ここ十五年くらいは、リモートワークやワーケーションの流行もあって、海辺の街でゆったり過ごそうという比較的若い移住者がどんどん増えていて、世代交代も進んでいる。

そんな街なので、夜の酔客も比較的大人しめの印象がある。それでも、移住者が優勢でなかった頃には、ときどき取っ組み合いの喧嘩があった。その発端には地元の漁師が絡むことが多かった。鎌倉は江戸期を通じてずっと小さな農村漁村で、ほとんどの住民は明治以降の転居でせいぜい三代。元から住んでいた村衆や漁師の方が先住民だ。特に漁師たちは江戸幕府が開かれて以来、天下の台所である日本橋の河岸(当時の魚市場)へ一番乗りで鰹を運び込んだりしていたので、鼻息は荒かった。だから、彼らの末裔にとって、比較的新しい気取った移住者(移住時期が明治であれ令和であれ)が新参者に思えるのは無理もない。漁師と新参者ではそれぞれの生活の背景や文化が違うので、お互い酔っ払っていると、ちょっとした言葉のあやで大喧嘩になる。ここ十年くらいはそういう大立ち回りはないけど、昔はよく仲裁に入った。漁師たちは、同じ鎌倉でも、実は生い立ちが違うのだ。言葉も独特の漁師言葉を使う。

Drinkers in Kamakura are generally quiet.

Kamakura was a deserted village long after the Kamakura Shogunate was abolished, but it opened as a resort town in the Meiji period and later became a commuter town for office workers commuting to Tokyo. The cultural figures who gathered there relying on their patrons who lived in villas have left, and the Shochiku film studio in Ofuna is gone, but thanks to the scenic area, the atmosphere of a calm resort still remains. Perhaps because of the climate, over the past 15 years or so, with the popularity of remote work and workation, the number of relatively young people who want to relax in the seaside town has been increasing, and a generational change is also progressing.

Because it is such a town, the nighttime drunks seem to be relatively quiet. Even so, when immigrants were not dominant, there were occasional fights. Local fishermen were often involved in the beginning of these fights. Kamakura was a small farming and fishing village throughout the Edo period, and most of the residents have been relocated since the Meiji period, at most three generations. The villagers and fishermen who lived there from the beginning are the indigenous people. Fishermen in particular were very active, as they were the first to bring bonito to the Nihonbashi riverside (the fish market at the time), the kitchen of the nation, since the Edo Shogunate was established. So it is not surprising that their descendants would see relatively new and pretentious immigrants (whether they immigrated in the Meiji or Reiwa eras) as newcomers. Fishermen and newcomers have different cultures, so when they are both drunk, they will get into a big fight over a small word. There haven't been any big fights like that in the last ten years or so, but in the past, I often intervened. Even though fishermen are from the same city of Kamakura, they actually have different origins. They also use a unique fisherman's language.

江戸時代より前は、関東にはまとまって大きな漁をするような集落はなかったが、江戸幕府が今の東京に置かれて人口が増えると、その様相は激変した。徳川家康は戦略だけではなく、ロジスティックにも長けていて、江戸の地を埋め立てて河川の付け替えをし、百万人の人口を支えられるだけの水源の確保や、運河による流通網を築き上げた。郊外農地からの野菜は神田河岸、魚介類は付近の漁村から日本橋河岸に集積されて、江戸城に運び込まれた。河岸の運営者たちは、江戸城に運び込んで余った荷を捌く権利をもらい、河岸は江戸庶民の台所にもなった。日本橋の河岸はその後築地に移転して栄え、その後豊洲に移転し、今に続いている。百万近い人口を支えるだけの需要があったわけで、江戸湾内だけでなく、房総沖や相模湾の漁獲物も江戸に運び込まれた。

当初は、相模湾の漁師が獲った魚を鎌倉から馬で峠を越えて金沢八景に運び、船で日本橋まで運んでいた。それでは鮮度が落ちるので、後には、小田原や鎌倉から特別仕立ての「押送船」で直接日本橋に搬送するようになった。押送船というのは、流線型の船体で尖った船首を持った小型の船で、脱着可能なマストと艪を併用する高速船だ。通常の帆船が風待ちで運行するところを、風の有無に関わらず人力の艪を使ってむりやり高速で目的地に向かう。小田原を夕方に出て、朝一番には日本橋に入ることが出来たそうだ。ただ、速度重視のため積載量が少なく、人件費もかかるので、魚の卸値も相応に跳ね上がる。それでも裕福な江戸っ子は新鮮な魚を欲しがった。鎌倉から刺身鮮度の鰹を運ぶのに、艪を七つも備えた押送船が使われた。屈強の漕ぎ手が昼夜を問わず漕ぎ続ける海の早飛脚というわけだ。

家康は、漁業の振興をするために、地元の三河や紀州などから漁業技術や魚介加工技術の専門家集団を関東に呼び寄せた。佃島が有名だが、房総や相模湾の漁村にも、そういった熟練の専門集団が送り込まれた。最新の漁船や釣具、魚網などの技術が、彼らによって飛躍的に発展した。押送船も紀州に起源を持つそんな技術の一つだったようだ。

Before the Edo period, there were no large fishing settlements in the Kanto area, but when the Edo Shogunate was established in what is now Tokyo and the population increased, the situation changed dramatically. Tokugawa Ieyasu was skilled not only in strategy but also in logistics, reclaiming land in Edo and redirecting rivers, securing a water source that could support a population of one million, and building a distribution network through canals. Vegetables from suburban farmland were collected at Kanda Riverbank, and seafood from nearby fishing villages were collected at Nihonbashi Riverbank, and then brought to Edo Castle. The operators of the riverbanks were given the right to sell any excess goods that were brought to Edo Castle, and the riverbanks also became the kitchens of the Edo common people. The Nihonbashi riverbank later moved to Tsukiji and flourished, and then moved to Toyosu, where it remains today. There was enough demand to support a population of nearly one million, so catches were brought to Edo not only from within Edo Bay, but also from the Boso coast and Sagami Bay.

At first, fish caught by fishermen in Sagami Bay were transported from Kamakura to Kanazawa-Hakkei by horseback over the mountain pass, and then to Nihonbashi by boat. Since the fish lost their freshness, later, they started to transport them directly to Nihonbashi from Odawara or Kamakura in specially made "oshisosen" boats. An oshisosen is a small, streamlined boat with a pointed bow, and is a high-speed boat that uses a detachable mast and oar. Whereas a normal sailing ship waits for the wind, this boat uses a human-powered oar to travel at high speed to its destination, regardless of whether there is wind or not. It was possible to leave Odawara in the evening and arrive at Nihonbashi first thing in the morning. However, because speed was emphasized, the loading capacity was small and labor costs were high, so the wholesale price of fish rose accordingly. Nevertheless, wealthy Edokko wanted fresh fish. An oshisosen with seven oars was used to transport fresh bonito for sashimi from Kamakura. They are fast couriers of the sea, with strong rowers rowing day and night.

To promote the fishing industry, Ieyasu summoned a group of local experts in fishing and seafood processing techniques from Mikawa and Kishu to Kanto. Tsukudajima is famous for this, but such skilled specialists were also sent to fishing villages in Boso and Sagami Bay. They dramatically developed the latest fishing boats, fishing gear, fishing nets, and other technologies. rapid ships seem to have been one such technology that originated in Kishu.

こういった漁師の交流によって、関東の漁村には互いに似た漁師言葉や漁師飯が伝わっている。叩いた魚に味噌を混ぜた、いわゆる沖飯だ。揺れる船上で、漁の合間に食べる早食いのための料理だ。生き餌にする鰯や鯵を使ったもの、沖で獲れる飛魚や鰹、イナダ、イカなどを使ったものがある。ざっと捌いた魚をまな板の上で包丁で叩いて味噌などの調味料を混ぜ、まな板から直接掬って食べたのだろう。揺れる船上でいちいち皿に盛る手間を省く工夫だ。叩いた魚は、直接ご飯に乗せても、汁に落としたり、茶漬けにしても良い。貝殻などに詰めて炙って食べても良い。土佐や紀州、沼津や伊豆にも類型の料理があるが、相模湾や房総の漁師に伝えられているのが、「なめろう」と「さんが焼き」だ。生のまま叩いて味噌で味付けしたものをなめろう、それをさらに焼いたものをさんが焼きと言う。お茶漬けにしたものは「まご茶」とか「まぐ茶」と呼ばれている。千葉の郷土料理として広く紹介されている。なめろうの語源については諸説があるが、その一つに「嘗(なめ)味噌」が語源という説がある。

嘗味噌は、調味料として使われる味噌ではなく、そのままおかずになる味噌のことだ。味噌や醤油の原型になった醤(ひしお)は、古代の中国を中心とした東アジアの食文化で、細く切った肉や魚、あるいは穀物や野菜に塩をまぶして発酵した副食の呼び名だ。中国では、その後生食自体の習慣は失われてしまったが、ひしおは広く東アジアで行われていた生食の文化の直系の遺産と言えるかもしれない。これは僕の推理だけど、この醤の原型に近い副食文化が嘗味噌として中国の辺境部に残ったのではないかと思う。漁師や船乗りが獲物を生食した後、塩や香草を混ぜて壺に保存し、発酵したものも食べるのは、ごく自然な流れだからだ。ヨーロッパでも、ローマ時代までは、魚介を塩蔵して、そのままあるいは調味料として使うことは広く行われていた。アンチョビーはその遺産の一つだ。生食の遺産は、実はアメリカ大陸にも伝わっているのではないかという僕の推理は、前のペルー料理に関する記事にも書いたので、ご興味のある方はご参照いただきたい。

さんが焼きの語源は、山仕事の時に持って行く弁当だったので、「山家焼き」という説があるが、やはり諸説ある。当時の漁師は海での漁だけで無く、山にも入って竹や木材を調達したり、猟もしたので、海仕事あるいは山仕事と呼び分けていた。

Through these exchanges between fishermen, similar fisherman's words and fisherman's meals have been passed down in fishing villages in the Kanto region. This is so-called okimeshi, which is pounded fish mixed with miso. It is a quick meal eaten on a rocking boat between fishing trips. There are dishes using live bait such as sardines and horse mackerel, and others using flying fish, bonito, Spanish mackerel, and squid caught offshore. The fish that were roughly filleted were pounded with a knife on a chopping board, mixed with miso and other seasonings, and then scooped directly from the chopping board and eaten. This was a way to save the trouble of having to serve the fish on a plate on a rocking boat. The pounded fish can be placed directly on rice, dropped into soup, or made into chazuke. It can also be stuffed into shells and grilled. Similar dishes exist in Tosa, Kishu, Numazu, and Izu, but the dishes that have been passed down to fishermen in Sagami Bay and Boso are "namero" and "sangayaki." When it is pounded raw and seasoned with miso, it is called namero, and when it is grilled it is called sangayaki. When it is cooked in ochazuke, it is called "magocha" or "magucha." It is widely known as a local dish of Chiba. There are various theories about the origin of the word namero, one of which is that it comes from "name miso."

Hishio is not miso used as a seasoning, but miso that can be eaten as a side dish. Hishio, the prototype of miso and soy sauce, was a side dish made by sprinkling salt on thinly sliced meat or fish, or grains or vegetables, and fermenting them in ancient China and other parts of East Asia. The practice of eating raw food was later lost in China, but it may be said to be a direct legacy of the culture of eating raw food that was widespread in East Asia. This is just my speculation, but I think that a side dish culture similar to the prototype of hishio remained in the outskirts of China. This is because it was quite natural for fishermen and sailors to mix their catch with salt and herbs, store it in a jar, and then eat the fermented version. In Europe, too, salting seafood and using it as it was or as a seasoning was widely practiced until the Roman era. Anchovies are one of those legacies. I have also written about my theory in a previous article about Peruvian cuisine that the heritage of eating raw food may have actually been transmitted to the Americas, so please refer to it if you are interested.

The origin of the name sangyaki is said to be "sanga-yaki" (grilled food for mountain house), as it was a lunch box brought to work in the mountains, but there are also various theories. At that time, fishermen did not only fish in the sea, but also went into the mountains to obtain bamboo and wood, and also hunted, so they called their work sea work or mountain work.

鎌倉では夏から秋口にかけ三浦沖で獲れた飛魚が出回るので、なめろうとさんが焼きを作った。

飛魚は、ヒレが発達した羽を自由に広げて、グライダーのように滑空することができる。100メートルくらいの距離を平気で飛ぶ。身体もそのために進化していて、流線型のボディーを持っている。また、大きなヒレを開いて揚力を得る必要があるので、それをささえるために発達した骨と固い身質を持っている。だから、身がねっとりと締まって非常に旨味が強い。幅のある刺身は取れないが、細切りの刺身にしても、たたきのように細かく切っても非常に美味い。特になめろうにすると絶品となる。アジアの沿岸部や南米でも常食されている。凝縮した旨味を持っているので、九州などでは、乾燥して出汁に使う。アゴ出汁の名前でラーメンなどにも使われている。

In Kamakura, flying fish caught off the coast of Miura are available from summer to early autumn, so I made namero and sangayaki.

Flying fish can freely spread their wings, which are made up of developed fins, and glide like gliders. They can easily fly distances of about 100 meters. Their bodies have also evolved for this purpose, and have a streamlined body. In addition, since they need to spread their large fins to gain lift, they have developed bones and hard flesh to support them. Therefore, the flesh is sticky and firm, and has a strong umami flavor. It is not possible to make wide sashimi, but it is very delicious whether it is sliced thin or cut into small pieces like tataki. It is especially delicious when made into namero. It is commonly eaten in coastal areas of Asia and South America. Because it has a concentrated umami flavor, it is dried and used as a soup stock in Kyushu and other places. It is also used in ramen and other dishes under the name of ago dashi.

Ingredients:

材料:

飛魚

味噌(好みの味噌で良い)

長ネギ(無くても良い)

紫蘇の葉(器になる葉ならなんでも良い。貝殻や竹皮、竹筒を割ったものでも良い)

Flying fish

Miso (any miso you like)

Leek (optional)

Shiso leaves (any leaves that can be used as a container are fine. Seashells, bamboo skins, or broken bamboo tubes are also fine.)

procedure:

手順:

飛魚の羽のようなヒレの脇から包丁を入れ、頭を落とす。三枚におろして、固い骨を外し、脇骨を削ぎ取る。

フィレの真ん中に骨があるので、骨に沿って包丁を入れ、身の部分を切り離して、皮を引く。

長ネギを刻んでおく。

(なめろう)

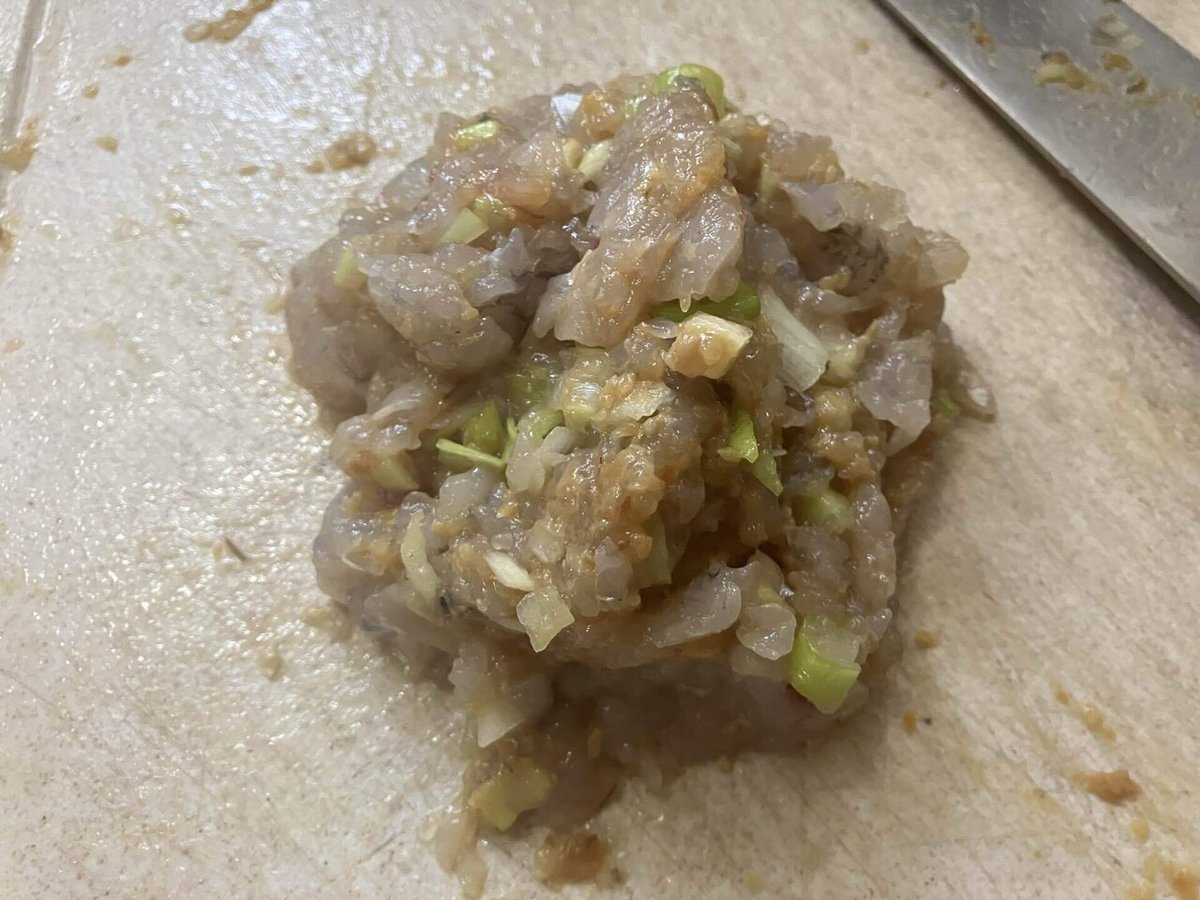

まな板の上で、味噌とネギを飛魚の身と一緒に包丁で、粘り気が出るまでたたく。

そのまま皿に盛ってサービスする。

(さんが焼き)

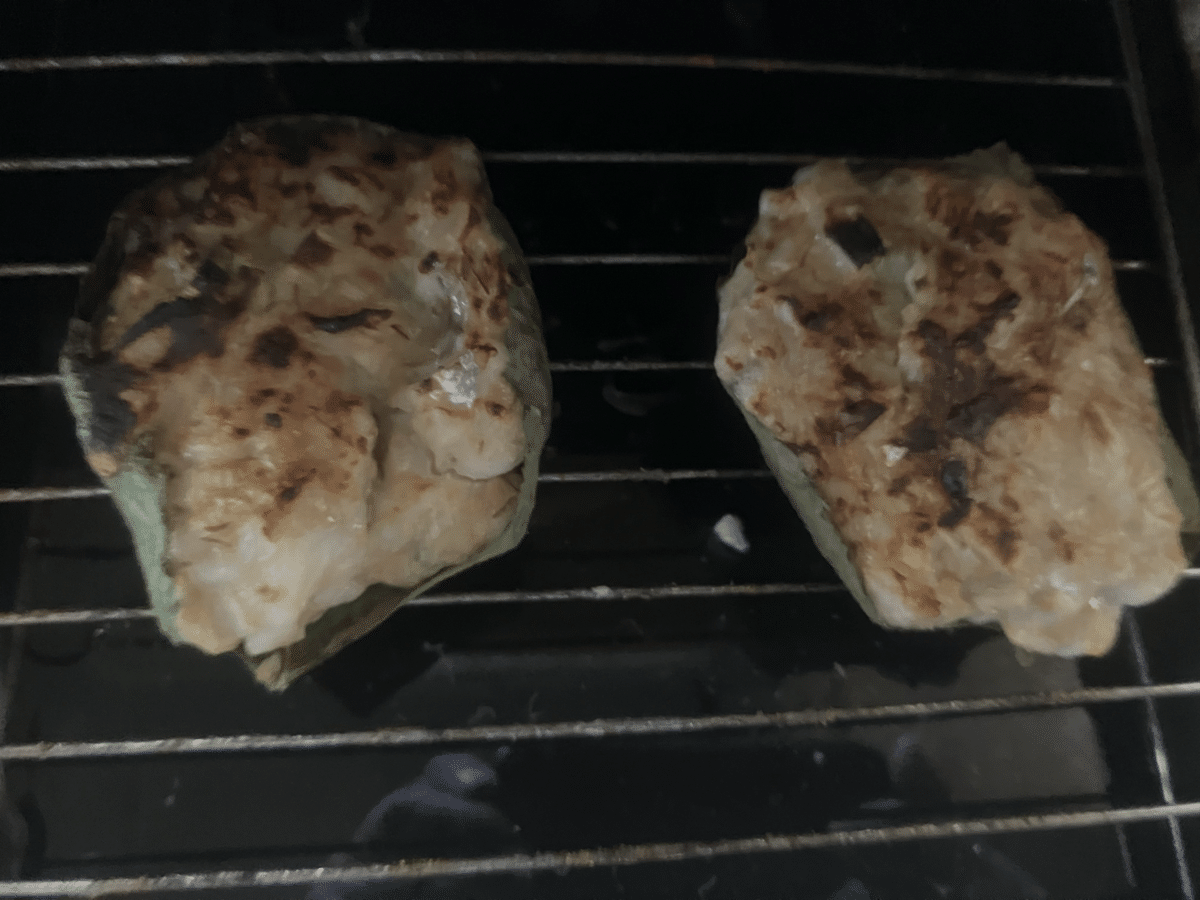

なめろうを、紫蘇の葉に乗せてグリルする。網で焼いたり油を敷いてフライパンで焼いても良い。

Insert a knife into the side of the flying fish's wing-like fin and cut off the head. Fillet the fish, remove the tough bones, and scrape off the side bones.

There is a bone in the middle of the fillet, so insert the knife along the bone, separate the flesh, and remove the skin.

Chop the green onions.

(Namero)

On a cutting board, beat the miso and green onions with the flying fish flesh with a knife until it becomes sticky.

Serve as is on a plate.

(Sangayaki)

Place the namero on shiso leaves and grill. You can also grill it on a wire rack or in a frying pan with oil.

Tips and tricks:

コツと応用のヒント:

飛魚のヒレは羽を支えるためにしっかり身に食い込んでいるので、その骨を先に外してから作業をすると、やり易い。飛魚の中骨は細かく粘りのある身に埋め込まれているので、骨抜きで抜くと身が崩れてしまう。だから、包丁を中骨の脇に入れて、五枚におろすと良い。

飛魚にはアニサキスなどの寄生虫がいる。ただ、鮮度が高い時は寄生虫は内臓にいて、身にはいないので、内臓を取れば安心して使える。鮮度が落ちると寄生虫は内臓から身に移動する。生食の前は、念のため光をあてて目視し、脇腹に米粒のような寄生虫がいないか調べると良い。見つけたら、包丁の先で取り除く。心配な場合は、焼き魚にするか、なめろうは諦めてさんが焼きだけ作ると良い。

ネギ以外に、三つ葉や山椒の葉など他の香草を使っても良い。チャービル、ディル、フェンネル、ミントなど、洋風やエスニック風のハーブを使ってもそれぞれ美味しい。

さんが焼きは紫蘇や荏胡麻を使えば、丸ごと食べられるけど、器と考えるなら、笹や葉蘭など好きな葉を使えば良い。鮑や蛤の殻に詰めて焼くと海鮮の鮮度を演出できる。また半分に割った竹筒などに詰めて焼くと青竹の香りが加わって一興。竹串に付けて、つみれ串に仕立てても良い。

なめろうは、沸騰した汁に落とせばツミレ汁として食べられる。

ご飯に乗せれば海鮮丼、ご飯に乗せた上から、お湯や出し汁、ほうじ茶などを注いでお茶漬けにしても、揚げても良い。応用範囲は広い。

ピーマンなどの野菜に詰めてドルマ風(トルコや中東の野菜詰め物料理。以前の記事で紹介してます)にして焼いたり煮込んだりしても良い、

飛魚の他、アジやイワシ、タイなどの白身魚、鰹やマグロの切り落とし、烏賊や海老などで作っても美味しい。

骨など、アラからは非常に上品な出汁が取れるので、焼いて干すか冷凍しておくと良い。

The fins of flying fish are firmly embedded in the flesh to support the wings, so it is easier to work with them if you remove the bones first. The backbone of flying fish is embedded in the fine, sticky flesh, so if you use a bone pick to remove it, the flesh will fall apart. Therefore, it is best to insert the knife next to the backbone and cut the fish into five pieces.

Flying fish contain parasites such as anisakis. However, when the fish is fresh, the parasites are in the internal organs and not in the flesh, so you can use it safely by removing the internal organs. When the fish loses freshness, the parasites move from the internal organs to the flesh. Before eating it raw, it is a good idea to hold it up to a light and visually check for rice-like parasites in the flank just to be sure. If you find any, remove them with the tip of a knife. If you are worried, you can grill the fish, or give up on the namero and just make sangayaki.

In addition to green onions, you can also use other herbs such as mitsuba and Japanese pepper leaves. Chervil, dill, fennel, mint, and other western or ethnic herbs are all delicious.

For san-yaki, if you use shiso or perilla, you can eat the whole thing, but if you want to use it as a container, you can use any leaf you like, such as bamboo or orchid. Stuffing it into abalone or clam shells and baking it will bring out the freshness of the seafood. Stuffing it into halved bamboo tubes and baking it adds the aroma of green bamboo, which is fun. You can also put it on a bamboo skewer to make a fishball skewer.

If you drop namero into boiling soup, you can eat it as fishballs soup.

If you put it on rice, it becomes a seafood bowl, or you can pour hot water, broth, or roasted green tea over the rice to make ochazuke, or you can fry it. It has a wide range of applications.

You can simmer peppers and other vegetables in a dolma-style sauce (a Turkish and Middle Eastern vegetable stuffing dish, which I introduced in a previous article) and then bake or stew them.

In addition to flying fish, it is also delicious with white fish such as horse mackerel, sardines, and sea bream, as well as off-cuts of bonito and tuna, squid, and shrimp.

A very refined broth can be extracted from the bones and other parts of the fish, so it is best to grill and dry or freeze them.

Guide to where to get ingredients and equipment 材料と機材の入手先ガイド

※Amazonのアフェリエイトに参加しています。もしご購入の際はここからクリックしてご購入いただけると、コーヒー代の足しになるので、嬉しいです。ちなみに僕はコーヒー依存症です。

*I participate in Amazon affiliate programs. If you purchase this product by clicking here, it will help pay for my coffee, so I would be verhy happy. By the way, I am addicted to coffee.