Self-consciousness emerging from gestural communication (Symbolic process beginning with “animal gestures”—Gendlin and Mead: 6)

The “self” accounted for in terms of the social process

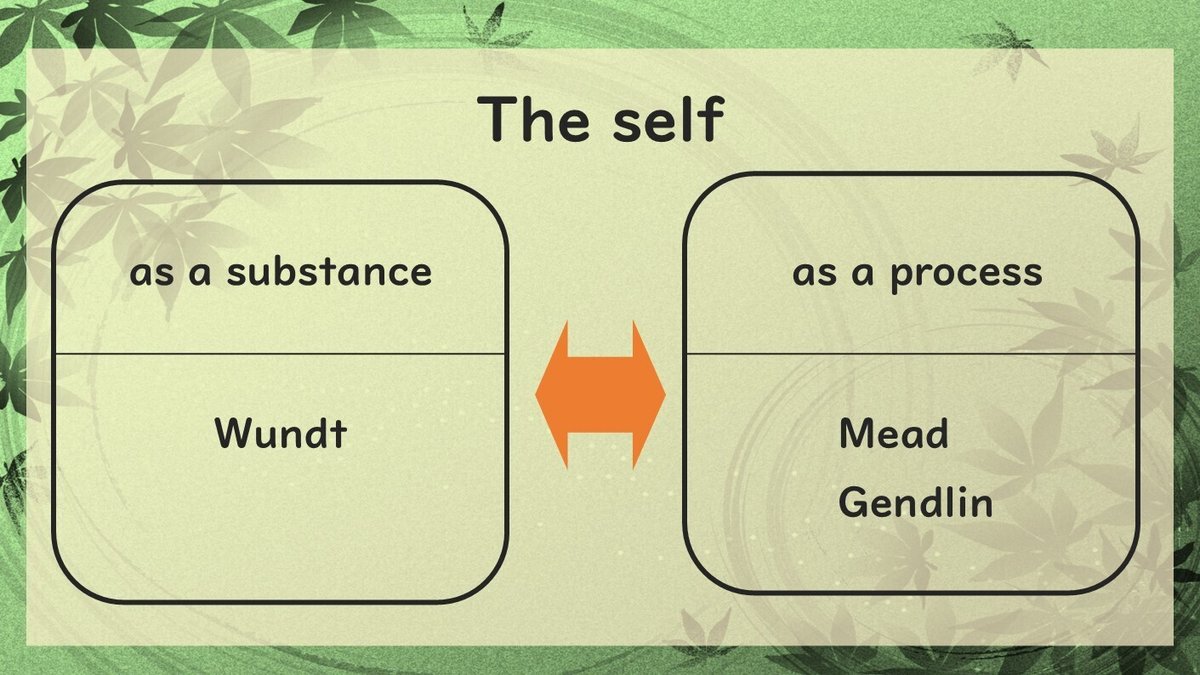

Mead (1934) had the following high opinion of Wundt (1900):

... Wundt isolated a very valuable conception of the gesture as that which becomes later a symbol, but which is to be found in its earlier stages as a part of a social act. (Mead, 1934, p. 42)

Meanwhile, Mead (1934) criticized Wundt (1900)’s view of the self as a substance or entity that exists independently of communication with other individuals:

The difficulty is that Wundt presupposes selves as antecedent to the social process in order to explain communication within that process, whereas, on the contrary, selves must be accounted for in terms of the social process, and in terms of communication... (Mead, 1934, pp. 49–50)

The self is not so much a substance as a process in which the conversation of gestures has been internalized within an organic form. This process does not exist for itself, but is simply a phase of the whole social organization of which the individual is a part. (Mead, 1934, p. 178)

This critical position was taken over by “A Process Model” (Gendlin, 1997/2018):

There are special further developments in which we can perhaps employ the word “self,” in a more usual way, but it will turn out to be very important to see that there is self-consciousness and a sense of self without there being an entity, a content, separate from other contents, that is said to be the self. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 125)

The evolution of gestures and the emergence of self-consciousness

In “Chapter VII-A: Symbolic Process” of “A Process Model,” there is a difference between the “animal gesture” in the section “a) Bodylooks” and the gesture in the true sense in the section “f) The new kind of CF.”

In the section f), “self-consciousness” is discussed for the first time. For example, the following passage can be mentioned:

So far our humans are human and self-conscious only in an interaction between at least two of them. The capacity to supply one’s own body-look cfing comes later. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 125)

However, such a discussion is abrupt, and it may be difficult for the reader to immediately connect the discussion of gestures and the discussion of self-consciousness just by reading this section.

If we go back to the discussion by Mead that Gendlin seems to have referred to, it seems to me that it is easier to understand that the evolution of gestures and the emergence of self-consciousness are related.

First, let's check the description of the gestures in “f) The new kind of CF”:

The new sequence can be called a gesture sequence in the true sense (whereas animal “gesture” is in quotation marks, not really a gesture). ... Once such a sequence is implied, a body-evev implies the other’s look and sound and moves, which, if it occurs on the other body, carries this one forward. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 122)

Next, I think that the above, “a body-evev implies the other's look and sound and moves” corresponds to the following quote from Mead, “to scream with an image of another individual”:

The fundamental importance of gesture lies in the development of the consciousness of meaning—in reflective consciousness. As long as one individual responds simply to the gesture of another by the appropriate response, there is no necessary consciousness of meaning. The situation is still on a level of that of two growling dogs walking around each other, with tense limbs, bristly hair, and uncovered teeth. It is not until an image arises of the response, which the gesture of one [life] form will bring out in another, that a consciousness of meaning can attach to his own gesture. The meaning can appear only in imaging the consequences of the gesture. To cry out in fear is an immediate instinctive act, but to scream with an image of another individual turning an attentive ear, taking on sympathetic expression and an attitude of coming to help, is at least a favorable condition for the development of a consciousness of meaning. (Mead, 1910, p. 178 [SW, 110–1])

Gestures may be either conscious (significant) or unconscious (non-significant). The conversation of gestures is not significant below the human level, because it is not conscious, that is, not self-conscious (though it is conscious in the sense of involving feelings or sensations). (Mead, 1934, p. 81)

Further developments alone on the grounds of our interactional human nature

We humans can think and reflect on things alone because we have had many experiences interacting with other individuals in our evolutionary history:

What we feel is interactional has to do with our living—in situations—with others. (Even the hermit is in a situation away from others. Further developments alone are of course possible, but on the grounds of our interactional human nature.) (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 193)

After a self has arisen, it in a certain sense provides for itself its social experiences, and so we can conceive of an absolutely solitary self. But it is impossible to conceive of a self arising outside of social experience. When it has arisen we can think of a person in solitary confinement for the rest of his life, but who still has himself as a companion, and is able to think and to converse with himself as he had communicated with others. (Mead, 1934, p. 140)

References

Gendlin, E. T. (1997/2018). A process model. Northwestern University Press.

Mead, G.H. (1910). What social objects must psychology presuppose? The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, 7(7), 174–80.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. (edited by C.W. Morris). University of Chicago Press.

Mead, G.H. (1964/1981). Selected writings [Abbreviated as SW] (edited by A.J. Reck). University of Chicago Press.

Mead, G.H. (1982). 1914 class lectures in social psychology. In The individual and the social self: unpublished work of George Herbert Mead (edited by D.L. Miller) (pp. 27–105). University of Chicago Press.

Wundt, W. (1900). Die Sprache (Völkerpsychologie : eine Untersuchung der Entwicklungsgesetze von Sprache, Mythus und Sitte, vol. 3). W. Engelmann.