What does “direct” in “direct reference” mean? Determine the difference between “reference” and “checking”

This article uses examples of conversations in Focusing sessions to clarify what the early Gendlin’s representative term direct reference in “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning” (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 91–100) does and does not denote. It is an English translation based on an article I contributed to the Japan Focusing Association newsletter just 20 years ago.

A more complete paper presenting my views on “direct reference” is included in a published book (Senses of Focusing, Vol. 1). The title of the paper is “Tapping ‘it’ lightly and the short silence: applying the concept of ‘direct reference’ to the discussion of verbatim records of Focusing sessions” (Tanaka, 2021).

I have disclosed the older version because it contains much not included in the newer version.

However, the older versions contain arguments that now seem juvenile. For example, I coined the term “indirect reference” at the time, even though Gendlin did not use it. I do not use this term now. This is because I later realized that “conceptualizing and checking,” which is what I wanted to say through the term at the time, was listed under “comprehension” in his book (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 117–27). However, I did not dare change it and included it as it is.

This article also deals with the issue of translating technical terms from English into Japanese. In that sense, it is certainly true that it contains issues that can only be found in the Japanese-speaking world. However, by examining how the polysemous English word “reference” is translated into foreign languages, I am proud to say that it deals with a universal issue that is not limited to the Japanese language, in that it reexamines the meaning of “reference” in the sense used by Gendlin.

Problem and Purpose

Gendlin calls the act of simply paying attention to the felt sense, saying “this,” “this feeling,” and so on, “direct reference.” Even with direct reference alone, a felt shift has been observed to occur. Direct reference is one of the most important acts of the Focuser.

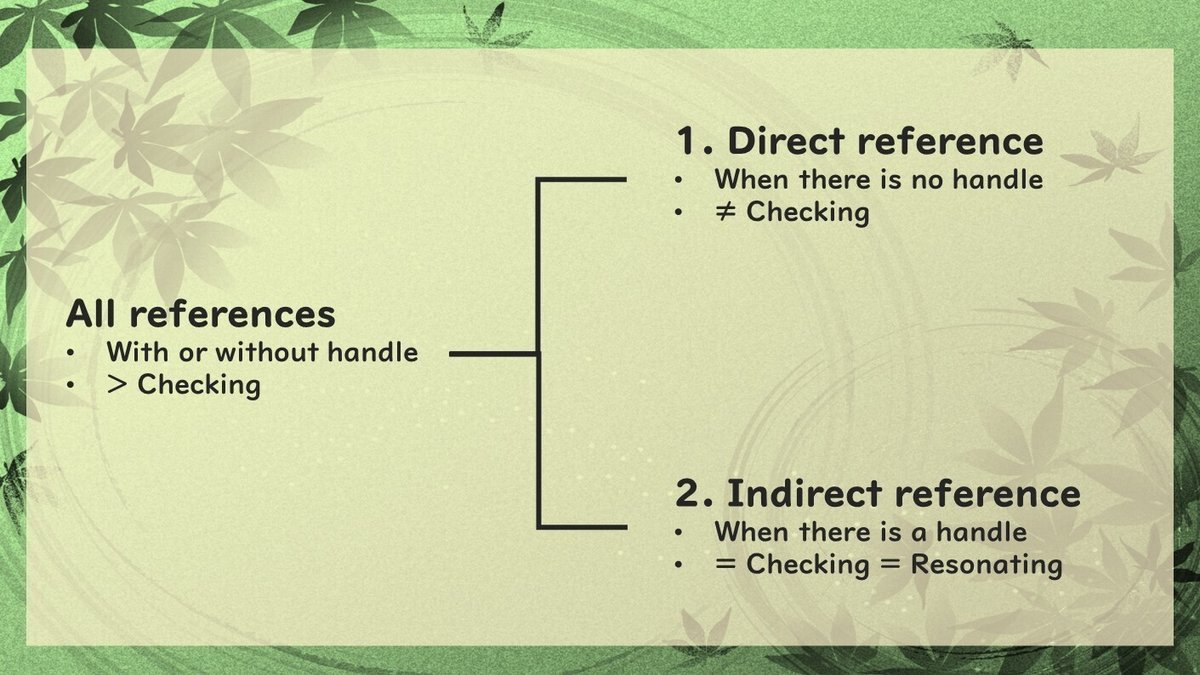

However, despite its importance, it seems that it has not been known what acts “direct reference” denotes and what acts it does not denote. One possible reason for this is that until now, the Japanese counseling literature has generally translated the word “reference” as “checking.” When reading the word “checking,” a reader familiar with Focusing will probably associate it with “resonating.” Resonating, by the way, is an act that can be performed only after the handle has been found. Therefore, “checking” implies that all references can only be performed after finding the handle. In reality, however, references can be made before the handle is found. This is because “reference” denotes all about paying attention to the felt sense.

My point is that the translation “checking” should be assigned only to reference where the handle has been found. This is because there is also a reference when the handle has not yet been found, which cannot be called “checking.” This reference that cannot be called “checking” is precisely the “direct reference” mentioned at the beginning of this article.

Therefore, the following explanation aims to understand the clear denotation of “direct reference.” First, I will give a specific example of Focusing; then, I will discuss the denotation of “direct reference” based on this particular example.

Example Conversation: Hypothetical Focusing Session

I will provide a specific example to help examine the denotation of the terminology associated with “direct reference.”

I have included below an example of a hypothetical Focusing session conversation. During the session, the Focuser’s inner act is divided into two types: the act when the handle is found and the act when it is not.

Focuser: Let me work on “this” for a moment. (Just sitting tight and paying attention to the tension in the right shoulder.)

Focuser: I think I’ll call it “sluggish.”

Listener: I see. At any rate, it could be called “sluggish,” as in...

Focuser: Oh, it’s not “sluggish” at all. I don’t know what to call it.

Focuser: Does it mean it’s “burdensome” to me?

Focuser: Yes, yes, it’s “burdensome”!

The above is a sample conversation from a fictitious Focusing session. In summary, the inner acts of the Focuser are roughly as follows:

Forming a felt sense.

Finding a tentative handle and resonating it with the felt sense.

Dropping the handles and touching the felt sense itself again directly.

Finding a more appropriate handle and resonating it with the felt sense.

Feeling a good fit.

These are just a few examples of what a typical session might look like.

Discussion Based on the Session

Based on the conversation examples above, I will discuss the denotations of terms such as “reference,” “direct,” and “checking.”

The following is the outlook of the discussion. First, I will review the denotation of “reference” in “direct reference.” Then, I will review the denotation of “direct” in “direct reference. This procedure will separate the references into “direct reference” and the other reference.

Next, I will approach “checking” as a word related to “reference” and examine its denotation. By examining the word, I will show where “checking” should be assigned to each classified reference.

Finally, I will explore why understanding the term “direct reference” has been hampered. To do so, I follow the history of “direct reference” and point out the problems involved.

1. Dividing “reference” into two cases

In the session above, “reference” is made in Focuser throughout the session, while “direct reference” is made only during part of the session. I will call the reference made during the rest of the session “indirect reference” for the time being.

1.1. What is “reference” in the first place?

The term “reference,” in Gendlin’s terminology, is “to pay attention to a felt sense while pointing to it.” In this meaning, “reference” is what the Focuser does throughout the session above.

The term “direct reference” refers to ... act of referring to a felt meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 93)

Also, in common usage, it can refer to anything. For example, the word “refer” can be used as follows:

The composer of “Just the Way You Are” refers to Billy Joel (or Bruno Mars?).

In Gendlin’s usage, on the other hand, the meaning of “reference” is “to pay attention to something while pointing to it. This is because “reference” is paraphrased as “pointing out,” “attention,” or “concentration” in his writings:

... the only necessary role played by symbols in direct reference is that of referring, that is, of specifying, pointing out, and setting off the felt meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 96; bold added)

By “reference” we mean ... only that attention is given to the feeling as such. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 93; bold added)

If you now try to define the term, you can observe what you do. In attempting to define it, you concentrate on your felt sense of its meaningfulness. Words to define it will arise, as it were, from this act of concentration on the felt meaningfulness. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 91; bold added)

Also, in Gendlin’s usage, referent is limited to what is inside a person since “referent” is limited to felt sense or words of that kind in his writings:

By “direct reference,” then, we shall mean an individual’s reference to a present felt meaning, not a reference to objects, concepts, or anything else that may be related to the felt meaning itself. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 94)

In summary, in Gendlin’s usage, the denotation of “reference” is “to pay attention to a felt sense while pointing to it.

In this meaning, “reference” is done through the abovementioned sessions. This is because the Focuser’s attention is directed to the felt sense in some way throughout the session above.

1.2. What is “direct reference” then?

Direct reference,” in Gendlin’s terminology, is “simply paying attention to a felt sense while pointing directly to it. By this meaning, “direct reference” is only one part of what the Focuser is doing in the session above.

In Gendlin’s writings, “direct reference” is often used more than just “reference.” So what is “direct”? How does “direct” limit the denotation of reference?

In his writings, Gendlin explains the meaning of “direct reference” as “saying something like “this feeling.” This explanation is the meaning of the qualifier “direct”:

... symbols are necessary for direct reference. The words “this feeling” or “this act” or “what I was going to do today”—these are symbols. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 95)

In direct reference, symbols (such as “this feeling”) refer without conceptualizing or representing the felt meaning to which they refer. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 95)

In this meaning, “direct reference” is only a part of the session above. This is because in the session, Focuser’s attention to the felt sense as he says “this” or “this feeling” is intermittent.

1.3. Divide “references” clearly into two cases

During the session, I divided references into two cases: “direct reference” and “indirect reference.” The standard for dividing cases is “no handle/handle.” The divided parts are then compared with each other. The difference is the words’ role in the felt sense (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 98). In either case, the role of words has advantages and disadvantages.

Subtracting the “direct reference” portion from all of the sessions above leaves the “other reference” portion. The left portion is not specifically named. So, for the time being, I will assign the term “indirect reference” to this kind of reference. I will explain why I called it “indirect” in the future.

The difference between “direct reference” and “indirect reference” is shown below as it applies to the session above:

The Focuser directly attends to the felt sense without finding the handle, just saying “this” or “this feeling.” At these points, the act of the Focuser is a “direct reference.”

The Focuser is paying attention to the felt sense by mediating handles such as “sluggish” or “burdensome.” At these points, the act of the Focuser is an “indirect reference.”

There is a difference between “direct reference” and “indirect reference” regarding the role that words play for the felt sense. In addition, when the role of the word is different, the scope of the referent to which the word refers is also different. These differences are described in detail below.

Case 1: Direct reference

“Direct reference” is an act in which words only refer directly to the felt sense.

... the only necessary role played by symbols in direct reference is that of referring, that is, of specifying, pointing out, setting off the felt meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 96; bold added)

“Direct reference” ... actually occurs only to the extent that the symbols depend for meaning entirely on felt meaning, and only point or refer to it. However, if we wish to, we may refer directly to our felt meaning even in cases where symbols do themselves mean the meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 99; bold added)

In this act, words such as “this” or “this feeling” have no specific meaning.

Apart from direct reference to felt meaning, the symbols mean nothing. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 100; bold added)

The role of these words is to point to a small point in an elusive stream of feeling.

Symbols ... Cannot attend to a feeling without reference with pointing symbols. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 112; bold added)

Symbols function as markers, pointers, or referring tools that create “a,” “this,” or “one” feeling by referring to “it.” (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 100; bold added)

These words also serve to make a point stand out from its surroundings.

“This feeling” or “a feeling” can occur only if something functions to refer to it, or specify it, or set it off, or mark it off. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 96–7; bold added)

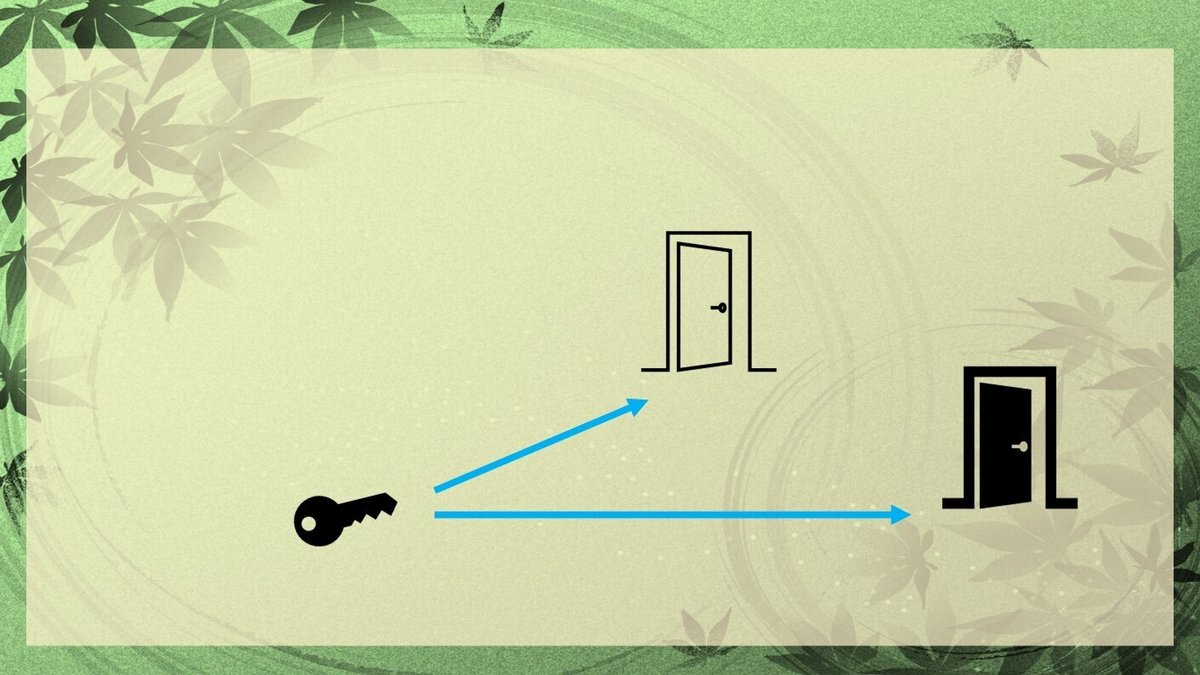

When the inner act of the Focuser is “direct reference,” words have their advantages. Words like “this” and “this feeling” can refer to any felt sense since they have no specific meaning. For example, in extreme cases, the same words “this feeling” can refer to the felt sense of chalk and the felt sense of cheese.

Or, if the quality of a felt sense changes as one continues to pay attention to it, one can continue to refer to it by the same word, “this feeling. The fact that these words can point to any felt sense is similar to the fact that a master key can open any door in any room.

However, when the inner act of the Focuser is “direct reference,” words have their disadvantages. Words such as “this” or “this feeling” have no specific meaning and thus cannot individually describe the quality of each felt sense. Because they do not describe the quality, these words are not very good at serving as handles when you want to recall a felt sense that you have let go of. For example,

“That feeling” at that time.

This phrase is not good at bringing back the felt sense.

The symbols, “this feeling,” mean a felt meaning only while they are employed in direct reference to that feeling. If that feeling disappears, the symbols have no power to bring it back. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 102; bold added)

Even while a person says “this feeling,” he is in danger of losing the specificity of the feeling and if he does, he has nothing with which to call it forth again and may never able to do so. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 105; bold added)

This is like the master key, which makes it impossible to tell which room you opened the door to the other day.

The pros and cons can be summarized as follows: When the reference only uses words such as “this” or “this feeling,” there is no “fit/unfit” with the felt sense.

Case 2: Indirect reference

“Indirect reference” is an act in which words refer indirectly to a felt sense. In this act, words such as “sluggish” or “burdensome” have specific meanings. The role of these words is to refer to the felt sense by using the word’s specific meaning as an intermediary. I have called this reference an “indirect reference.” It cannot be called “direct” because it involves an intermediary.

When the inner act of the Focuser is an ‘indirect reference,’ words have advantages. Words such as “sluggish” or “burdensome” have their specific meanings and thus can somewhat describe the quality of the felt sense.

The symbols function to express, delineate, explicate, represent, conceptualize (other words are equally descriptive) the felt meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 108; bold added)

Because they can describe the quality, these words are good at serving as handles when one wants to bring back a felt sense that you have almost let go of. For example,

I think I ended up with the handle “burdensome” the other day ... Oh, now I remember. Oh yes, that is it!

These words that serve as handles also bring back the felt sense.

... the symbols have the power to mean, that is, to call forth recognition feeling. The symbols have this power even apart from the presence of felt meaning. Close the book and open it tomorrow; the symbols will then do their work again. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 102; bold added)

Symbols, when presented to us, call out felt meanings in us (provided we “know” the symbols). (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 103; bold added)

However, when the inner act of the Focuser is “indirect reference,” words have their disadvantages. Words such as “sluggish” or “burdensome” have their specific meanings, which limits the felt sense to which they can refer. For example, you cannot use the word “sluggish” to refer to a relaxed or energetic sense. (Even though “sluggish” can refer to all kinds of sluggishness, it cannot refer to any felt sense.)

Also, if one keeps paying attention to a certain felt sense, one may find that the felt sense has a different quality, and then it often happens that you can no longer continue to point with the same words. Its typical example is the change from “sluggish” to “burdensome.”

The pros and cons can be summarized as follows: It is only when the referent uses words such as “sluggish” or “burdensome” that the dimension of “fit/unfit” with the felt sense becomes an issue.

2. Reconsider “Reference” in Relation to “Checking”

This section discusses how to assign a translation to “reference” to avoid confusing the case divisions of “reference.” Therefore, I will use “checking” as a term related to “reference.” Until now, “checking” has been used in Japanese literature as a translation corresponding to “reference.” However, “checking” is inappropriate when applied to all references.

2.1. Questioning the Denotation of “Checking”

Let us examine the meaning of the word “checking.” It turns out that “checking” corresponds to “resonating” in today’s Focusing terminology.

If you look up “check” in the dictionary, you will find the usage “check A against B” or “check A toward B.” In Japanese and English, to check means to put two things together and examine what is the same and different. The word “check” cannot be used when there are no two things or when there is no way to check them, even if they exist.

In common usage, it is used to check fingerprints left at a crime scene against a criminal’s fingerprints found in another case.

On the other hand, if we use the term in the context of Focusing, we would use it to mean “checking the handle against the felt sense. Then “checking” would have the same meaning as “resonating” in today’s Focusing terminology.

In this sense, in the session above, “checking” would only apply to reference using a handle. This is because, without a handle, there is no way to check (or resonate) with the felt sense in the first place.

2.2. Reassigning the Translation “Checking”

Based on the above, I conclude and suggest the following as to where the word “checking” should be assigned in the case-specific references:

I consider that “checking” should be assigned only to “indirect reference” and not all references. In other words, it should not be assigned to “direct reference.”

This conclusion can be graphically illustrated as follows:

In Gendlin’s writings, reference is much more often used in the sense of “direct reference.” Conversely, it is used much less frequently in the sense of “indirect reference” (i.e., resonating). Thus, the ironic result of translating all references as “checking” is that the most frequently used meaning is dropped, and the rarely used meaning is given prominence. To avoid such an ironic result, I thought it would be better to translate only “indirect reference” as “checking.”

3. The History and Problems of “Direct Reference” and “Checking”

My proposal itself is above. In what follows, I will highlight the problems with the term “direct reference” by tracing its history. I consider that there is a good historical reason why the meaning of “direct” in “direct reference” has never been questioned.

There are two possible reasons for this. First, Gendlin himself wrote in a way that made the division of reference ambiguous. Second, even before Gendlin’s writings were introduced to Japan, “reference” was commonly translated as “checking.”

3.1. History of “Direct Reference” in Gendlin’s Writings

The term “direct reference” was first clearly defined in “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning” (Gendlin, 1962/1997). However, in his later paper, “A Theory of Personality Change” (Gendlin, 1964), the term was used with a somewhat ambiguous meaning. This may be one of the reasons why the meaning of “direct” in “direct reference” has received less attention.

“Direct reference” was first mentioned in his book “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning” (ECM). In this work, direct reference was clearly distinguished from the others in terms of the role of words. Primarily in Chapter 3 (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 91–137) of ECM, the distinction of the role of words is examined in detail. For example, the following passage is mentioned:

In direct reference, symbols (such as “this feeling”) refer without conceptualizing or representing the felt meaning to which they refer. Thus the role of symbols in direct reference is distinguishable from other roles symbols can have, because in direct reference there need no conceptualization at all. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 95)

Thus, in terms of the role of words, it distinguishes the act performed when the handle has not yet been found from when the handle has been found. ECM is groundbreaking in theoretically elucidating the role of words for the felt sense in “direct reference.”

“Direct reference” was second mentioned in his paper “A Theory of Personality Change.” In this paper, “direct reference” was, in some ways, more fully explained, and in others, it was more vaguely explained.

“A Theory of Personality Change” contains a more detailed “direct reference” explanation. The paper includes the results of an empirical study of direct reference. The study was based on physiological measurements of the inner experiencing mode of subjects in a laboratory setting. In current Focusing terminology, this measurement results can be summarized as follows: A shift (relief or tension reduction) can occur simply by maintaining direct attention to the felt sense (Gendlin et al., 1961). The study’s results were first incorporated into “A Theory of Personality Change. “The paper was groundbreaking in providing a theoretical explanation for the “effects” of direct reference in psychotherapy.

At the same time, however, “A Theory of Personality Change” contains a more ambiguous explanation of “direct reference. In this paper, there is a section entitled “8. Direct Reference in Psychotherapy. Here, despite the title “Direct Reference,” the section contains some references to “indirect reference” (i.e., checking or resonance). For example,

He [the individual] forms concepts and “checks them against” his directly felt meaning and, on this basis, decides their correctness. (Gendlin, 1964, p.117)

Thus, although the section intends to explain the act to be performed when the handle has not yet been found, it also describes the act of finding the handle and making the handle resonate with the felt sense. Therefore, compared to ECM, I cannot help but feel that the reference division has become somewhat blurred. I consider this to be one of the reasons why the meaning of “direct” in “direct reference” has not received much attention.

3.2 History of the Translation “Checking”

The custom of translating “reference” as “checking” existed before Gendlin was introduced to Japan, which may explain why the translation “checking” is still used today.

The first translator of Gendlin’s term “reference” was probably Takao Murase. He has intentionally changed the translation of the word reference since the middle of his work.

When Murase first translated one of Gendlin’s papers (Gendlin, 1961), he used “checking” as the translation for reference. The editors of the volume in which this translation was included have unified the translation “checking” for all volumes in the series (e.g., Internal frame of checking). Thus, it is likely that Murase followed the policy of the entire collection when he used the word “checking” in his first translation of Gendlin’s text.

However, when Murase reprinted the same paper two years later in another collection, he changed the translation of the word “reference” from checking to “refarensu”. In other words, it was transliterated. In one of the notes to the volume, he wrote that he did not translate the word “reference” as “checking” because it did not include all the connotations of “reference. In other words, he thought that Gendlin’s reference was “reference > checking” in terms of the breadth of its meaning. Thus, it is likely that he dropped the word “checking” in the second translation to make Gendlin’s intent more straightforward.

However, there are still instances where Gendlin’s reference is translated as “checking.” The translation has not been unified. As described above, the translation of Gendlin’s reference has fluctuated historically, which continues to this day.

4 Conclusion and Future Issues

The boundary of reference and the much greater prominence given to the act of “direct reference” is one of Gendlin’s significant achievements in psychotherapy. Therefore, I consider that we should assign a spic and span translation to this distinction so as not to mix up the two kinds of references. For example, the translation “checking” should be assigned only to “indirect reference.” Examining how translations are assigned this way will help us understand what Gendlin intended to say more easily.

One of my future tasks is to develop a more coherent and precise translation of Gendlin’s term “reference.” This time, I suggested where to assign the translation “checking,” but I could not develop a translation that would apply to all references. It may be acceptable to leave the transliteration as it is now, but it would be better if a more suitable Japanese word could be found. As a Focuser, I would be happy if someone could use my writing as a starting point and suggest a more “fitting” translation.

I want to revisit this issue in the future, including Gendlin’s recent writings, because my reference is limited to Gendlin’s earlier writings.

References

Gendlin, E.T. (1961). Experiencing: A variable in the process of therapeutic change. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 15(2), 233–245.

Gendlin, E. T. (1962/1997). Experiencing and the creation of meaning: a philosophical and psychological approach to the subjective (Paper ed.). Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1964). A theory of personality change. In P. Worchel & D. Byrne (eds.), Personality change (pp. 100–148). John Wiley & Sons.

Gendlin, E.T. & J.I. Berlin (1961). Galvanic skin response correlates of different modes of experiencing. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 73-77.

Tanaka, H. (2004). What does “direct” in “direct reference” mean? Determine the difference between “reference” and “checking.” [in Japanese] The Focuser’s Focus: Japan Focusing Association Newsletter, 7(2), 1–6.

Tanaka, H. (2021). Tapping ‘it’ lightly and the short silence: applying the concept of ‘direct reference’ to the discussion of verbatim records of Focusing sessions (with the English language supervision of Akira Ikemi). In Nikolaos Kypriotakis & Judy Moore (Eds.), Senses of Focusing, Vol. 1 (pp. 125–38). Eurasia Publications.