What I really wanted to tell in the @GlobalVoices 'introductory' #MeToo story on Japan (1/4)

Last updated: 2019/2/11 | Original Japanese

INTRODUCTION

This is the article I wrote about "#MeToo in Japan" for the first time as contributing Citizen Writer to Global Voices in February 2018. The article didn't really capture in full what I wanted to tell that it disheartened me.

As I wrote in my post-production notes on Twitter in Japanese, The three critical points I wanted to make in my first #MeToo publication was:

1. Deficiency in Japan's legal system;

2. Lack of awareness and training in law enforcement about treatment of victims of sexual violence; and

3. Lack of enactment of policy to examine the excess and/or deficiency to support social safety nets on the ground.

However, it was almost impossible to incorporate all of these in the published article given the limitations in its volume and its complexity. The editors wanted a more 'introductory' article to #MeToo in Japan. But this was hard for me to take when I have just encountered a 'third' #MeToo . An 'introduction'? Now? But for the publication I went along with the editing policy and realigned my original text accordingly.

A few days ago before I wrote the Japanese version of this Introduction last year, UK's BBC aired a documentary program entitled, "Japan's Secret Shame". It featured Shiori Ito, a freelance journalist and activist who has been advocating for sociopolitical reform surrounding sexual violence victims. She herself was a victim of sexual violence.

The BBC program endeavored to cover Shiori's engagement over the nine month since she went public on her rape case. The program somewhat captured the three critical points that I wrote earlier, but it really wasn't enough. So I asked the Regional Editor if I can revive the rejected portion of the article - which I already obtained consent from the interviewees for publication. His answer was quick and simple:

"Sure. It's YOURS. You own the copyright."

It turns out that may be I didn't even have to ask for consent in the first place.

So here it is. The full English translated version of the article including the rejected portion of the published article. It includes additional text that were not perfected as result of the initial edit of the original text.

#MeToo in #Japan (Part 1) - Third "MeToo" names the alleged assailant from the theaters

In December 2017, the #MeToo movement finally reached Japan after three women decided to speak out against their abusers.

The experiences of these three women provide insights into the challenges Japanese women face when speaking out about their experiences of sexual assault.

Shiori Ito - Freelance Journalist

While the #MeToo movement is generally regarded to have started in October 2017, when multiple women spoke out about their experiences of being allegedly sexually assaulted by Hollywood movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, the movement got its start in Japan in May 2017 when the hashtag #FightTogetherWithShiori started to trend on Japanese Twitter. The hashtag was created in support of a woman, known simply at the time as “Shiori”, who appeared on television to allege she was sexually assaulted by a well-known journalist in 2015.

In October 2017, thanks to support across Japan and around the world, Shiori Ito decided to reveal her full name and published a book, “Black Box.”

Shiori Ito, who is best known simply as ‘Shiori’, also frequently appears in numerous interviews both seeking justice and to highlight the problem of sexual assault in Japan.

After Shiori’s debut in the public spotlight, and as the #MeToo movement in the United States and other countries gained momentum, other women started making their voices heard on social media.

Hachu - Blogger, Writer

In December 2017, a blogger known simply as Hachu helped bring the #MeToo hashtag to Japan after her story was published by Buzzfeed Japan.

Hachu, a popular writer and blogger, revealed that she had been sexually harassed by one of her managers, a well-known creative director in Japan’s advertising industry, while she was working at the advertising giant Dentsu.

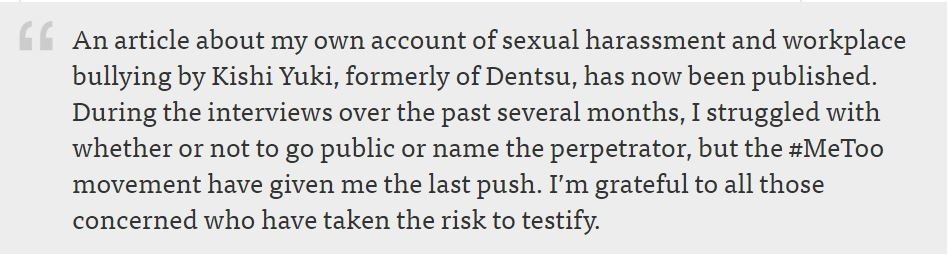

Hachu’s tweet about the Buzzfeed story was shared on Twitter 17,000 times:

Hachu’s story, which was first published in mid-December, prompted others to share their stories. In late January 2018, a third “#MeToo” story generated conversation on social media in Japan.

Shimizu Meili - Stage actress

Web magazine wezzy reported that stage actress Shimizu Meili, who goes by ‘Meili’ on social media and in interviews ? disclosed on Twitter that she had been sexually assaulted by her stage producer Takeuchi Tadayoshi.

Tadayoshi produces the stage genre of ‘2.5D’ anime theater which features dramatizations of Japanese manga set to music.

Meili met him for the first time on that fateful day.

2.5D theater enjoys a large fanbase so Meili went public with the allegation first by tweeting about her sexual assault but without naming the perpetrator.

Meili compiled her own Tweets into a Twitter Moment entitled “The Reason I Cried at the February Performance”.

After her December Twitter posts went viral, they were picked up by web magazine wezzy. Later that month, when Hachu’s #MeToo story was reported by Buzzfeed, Meili felt prompted to name her own accuser.

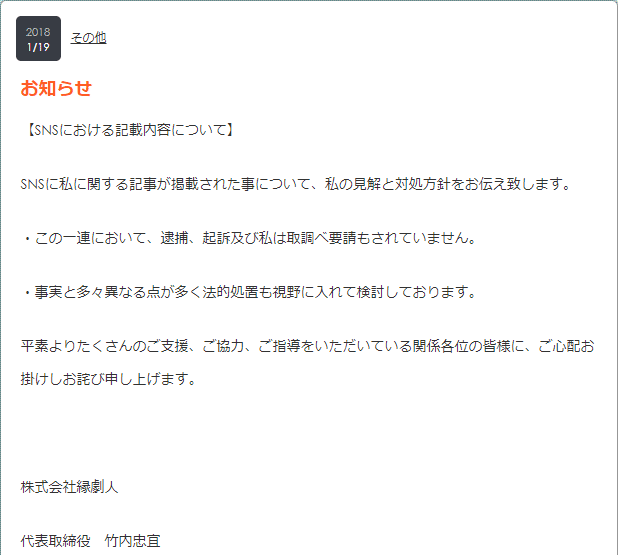

The alleged producer, Takeuchi issued a formal statement on his company website, on the same day.

"I was neither arrested or asked to be interrogated [by the police]. Many of her allegations are not factual and I am considering to take legal measures if necessary."

Unfortunately, some of his assertions are true.

What happened over the next month provides insights into the struggle faced by victims of sexual assault in Japan.

いいなと思ったら応援しよう!