The Past in the “Here and Now”

I received the incentive award from the Japanese Association for Humanistic Psychology in 2021. The following year, I gave a lecture commemorating the award in Japanese. I have now prepared the additional English title and abstract of the lecture.

Title

Hideo Tanaka (2022, September). The Past in the “Here and Now”. (The incentive award commemorative lecture is in Japanese.) Presented at the 41st Conference of the Japanese Association for Humanistic Psychology.

Abstract

The “here and now” is one of humanistic psychology’s traditional and central themes. However, there is currently no consensus among researchers and practitioners of humanistic psychology as to what is meant by the term “here and now.” In this presentation, based on the results of a research study by Eugene Gendlin and others (Gendlin et al., 1960) and his philosophical term “retroactive past” (Gendlin, 1991), I will examine the past as it is reinterpreted in terms of the “here and now.” Based on this examination, the relationship between the present and the past in the writings of Carl Rogers and Fritz Perls (Rogers, 1970; Perls, 1973) will be considered. I hope this consideration will provide an opportunity to discuss the importance of the “here and now” in humanistic psychology.

Some quotes & slides

Current Status and Issues

When I participated in a basic encounter group, I had the experience of being urged by a relatively directive facilitator not to "talk about the past" but to “talk about the ‘here and now.’” (Morotomi, 2009, p. 39)

Early Research Study: How the Clients Talk

6. To what extent does the client express his feelings, and to what extent does he rather talk about them? (This scale differentiates direct expression from report about one's feelings, regardless of whether the feeling is past or present).

Example:

“It comes to me now how scared I really was last night.”

“I was scared last night.”

(Gendlin et al., 1960, p. 211; Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 249; bold added)

... as to content it might well be about a past event, for example, intensely experiencing sadness now, about events of long ago. (Gendlin et al., 1968, pp. 222-3)

Later Philosophical Discussion: Two Pasts

There are two pasts, two ways the word “was” can work: One is the retroactive past, made from the carrying-forward occurrence of what was implied. The other is the remembered past behind us on the linear track. Certainly, sometimes we do confuse these two. And, that is just because they are not the same. (Gendlin, 1991, p. 65)

Previous Study on “Retroactive Past”

“Oh, now I know what it was. I was afraid of her all this time.” (Ikemi, 2017, p. 167; bold added)

It is not because you were able to say what you wanted to say that you got it off your chest, but because you got it off your chest that you know it was what you wanted to say. (Chikada, 2002, p. 59; bold added)

The present ... gives the past a new function, a new role to play. ... Not only is it interpreted differently, rather, it functions differently in a new present.... (Gendlin, 1996, pp. 14-5)

...for that past must be set over against the present within which the emergent appears, and the past, which must then be looked at from the standpoint of the emergent, becomes a different past. (Mead, 1932, p. 2)

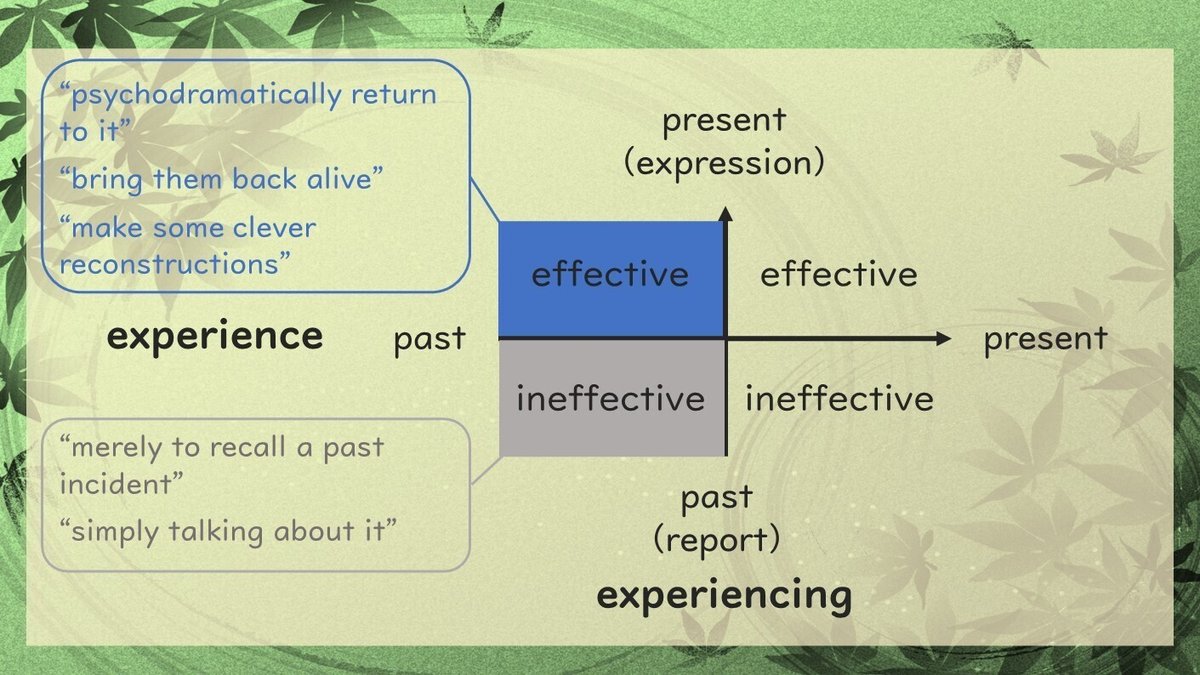

Experience vs. Experiencing

Because of the lack of precise terms, Rogers' emphasis on present experience has been widely misinterpreted to mean that a client need not deal with his past experience. In such a reading of his view, Rogers' reference to the present is taken to refer to conceptual content. Rogers is misunderstood to mean that a client need only deal with the content of his present life, not with his early experience. However, Rogers means that whatever the client deals with (past or present conceptual content), it is optimally dealt with only through present experiencing. (Gendlin, 1958, p. 13; 1962/1997, pp. 247-8; bold added)

Matrix

Reinterpretation of Rogers

I respond more to present feelings than to statements about past experiences but am willing for both to be present in the communication. I do not like the rule: “We will only talk about the here and now.” (Rogers, 1970, p. 50; bold added)

Reinterpretation of Perls

It is insufficient merely to recall a past incident, one has to psychodramatically return to it. … the memory of an experience—simply talking about it—leaves it isolated as a deposit of the past-as lacking in life as the ruins of Pompei. You are left with the opportunity to make some clever reconstructions, but you don’t bring them back alive. (Perls, 1966, pp. 65-6; bold added)

Reorienting the “Here and Now”

References

Chikada, T. (2002). Counseling basics with Focusing: to make client-centered therapy really useful [in Japanese]. Cosmos Library.

Gendlin, E.T. (1958). The function of experiencing II. two issues: interpretation in therapy; focus on the present. Counseling Center Discussion Paper (University of Chicago), 4(3), 11-5.

Gendlin, E.T. (1962/1997). Experiencing and the creation of meaning: a philosophical and psychological approach to the subjective. Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1991). Thinking beyond patterns: body, language and situations. In B. den Ouden, & M. Moen (Eds.), The Presence of Feeling in Thought (pp. 21-151). Peter Lang.

Gendlin, E.T. (1996). Focusing-oriented psychotherapy: a manual of the experiential method. Guilford Press.

Gendlin, E.T., Jenney, R.H. & Shlien, J.M. (1960). Counselor ratings of process and outcome in client-centered therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(2), 210-3.

Gendlin, E.T., J. Beebe, J. Cassens, M. Klein & M. Oberlander (1968). Focusing ability in psychotherapy, personality and creativity. In J.M. Shlien (Ed.), Research in psychotherapy. Vol. III (pp. 217-41). APA.

Ikemi, A. (2017). The radical impact of experiencing on psychotherapy theory: an examination of two kinds of crossings. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 16(2), 159-72.

Mead, G. H. (1932). The philosophy of the present (edited by A. E. Murphy). Open Court.

Morotomi, Y. (2009). The origin of Focusing: basic characteristics of its philosophy and its relationship with Rogers [in Japanese]. In Morotomi, Y. (ed.) The origins and clinical development of Focusing (pp. 3-41) [in Japanese]. Iwasaki Gakujutu Shuppansha.

Perls, F. (1973). The Gestalt approach & eye witness to therapy. Science & Behavior Books.

Rogers, C.R. (1970). Carl Rogers on encounter groups. Harper & Row.

Tanaka, H. (2016). Process variables in Gendlin’s psychotherapy research [in Japanese]. Kandai Psychological Reports (Graduate School of Psychology, Kansai University), 16, 105-11.