Anthology: Dilthey as a Precursor of Gendlin

Perhaps the most radical impact of my philosophy today stems from Wilhelm Dilthey. It is something Heidegger approached but lacked. This vital part of Dilthey’s works (vol. 7) was published later, when Heidegger was no longer reading Dilthey. (Gendlin, 1997a, p. 41)

I often quoted from the German Dilthey Collected Works, Volume 7, in my paper “A bibliographical survey of E.T. Gendlin’s early theory of experiencing: influences of W. Dilthey’s philosophy on his psychotherapeutic studies” (Tanaka, 2004–5), almost twenty years ago. Based on this experience, I would like to contribute to an anthology of Dilthey’s writings.

However, it should be noted that what I write in this post will not lead to a direct understanding of “A Process Model” (Gendlin, 1997/2018). This is because Dilthey’s philosophy is about the foundation of the human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften) and does not focus on the interaction between the body and its environment or the body as a plant or animal.

About “Erleben” = “experiencing”

Before presenting the anthology, I would like to make one more proviso.

Many people interested in Gendlin’s theory know that “experiencing” was proposed as the translation of the German word “Erleben.”

At the time of writing his master’s thesis, Gendlin made a clear distinction between “experiencing” and “a unit experience,” before he started working in psychotherapy with Carl Rogers in 1952 (Gendlin, 2002, p. xi):

When Dilthey speaks of ... Erfahrung, we shall here say “experience” and refer to the totality of experience considered as a whole process. When Dilthey speaks of erleben (to live through), we shall here say “experiencing”, referring to the process or functioning [*1]. Dilthey's word Erlebnis means a unit experience. (Gendlin, 1950, p. 13)

However, a closer examination of Dilthey’s primary literature reveals that in most cases, Dilthey used the nouns Erleben and Erlebnis without distinguishing between them. This fact contrasts with his contemporary Edmund Husserl, who made a strict distinction between them (Mimura, 2015, p. 70).

In conventional English translations of Dilthey, it is common to translate both Erleben and Erlebnis as “lived experience” without distinguishing between them.

Erlebnis is often translated as “lived experience” to distinguish it from the more ordinary experience designated by Erfahrung. ... The phenomena of Erlebnis are given with certainty; whereas the objects of external experience are at least partly products of inference. ... Dilthey does indeed often treat Erlebnis and innere Erfahrung [inner experience] as if they referred to the same thing. (Makkreel, 1992, pp. 147–8)

Thus, in what follows, I cite Dilthey’s texts translated as “lived experience” without distinction as the source of Gendlin’s idea of “experiencing.” [*2]

Anthology

In Gendlin’s master’s thesis, volume 7 of the German Dilthey works (Gesammelte Schriften) is cited most often, followed by volume 5. Therefore, the following anthology will also be quoted from these two volumes. The two volumes were fully translated into English and published from the late 1990s to the early 2000s (Dilthey, 1996; 2002).

1. “Life (Leben)” or “lived experience (Erleben)” as a starting point for human sciences

Life [Leben] is the basic fact that must form the starting point of philosophy. Life is that with which we are acquainted from within and behind which we cannot go. We cannot bring life before the tribunal of reason. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 280; 1927, p. 261)

Since lived experience [Erleben] is unfathomable and no thought can go behind it, since cognition itself only comes about in relation to it, since consciousness of lived experience [Erleben] is infinite, not just in the sense that it is insoluble by its very nature. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 245; 1927, pp. 224–5)

2. Immediacy of “lived experience”

“Experiencing” ... is a concrete mass in the sense that it is “there” for us. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p.11)

Notice, it [Experiencing] is always there for you. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p.13)

Sorrow about something is experienced or there for me [für mich da] as an attitude. Likewise a desire for something. No matter how this is accounted for psychologically, the certainty of lived experience requires no further mediation. It can accordingly be called immediate. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 47–8; 1927, p. 26)

All knowledge of psychic objects is founded on lived experience [Erleben]. ... Lived experience [Erleben] is always certain of itself. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 46–7; 1927, pp. 25–6)

The noise that a feverish patient relates to an object behind his back forms a lived experience [Erlebnis] that is real in all its parts. Both the occurrence of the noise and its being related to the object are real. And the fact that the assumption of an object situated behind the bed is false does not affect the reality of this fact of consciousness. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 47; 1927, p. 26)

3. Relationship between the present and the past in “lived experience”

Because of the lack of precise terms, Rogers' emphasis on present experience has been widely misinterpreted to mean that a client need not deal with his past experience. ... However, Rogers means that whatever the client deals with (past or present conceptual content), it is optimally dealt with only through present experiencing. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 247-8)

The principle of lived experience [Der Erlebnissatz] is that everything that is there for us [für uns da ist] is so only as a given in the present. Even when a lived experience [Erlebnis] is past, it is only there for us as given in a present experience. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 250; 1927, p. 230)

When we remember lived experiences, we can distinguish the manner in which they continue to have a (dynamic) efficacy in the present from lived experiences that are completely past. In the first case, feeling as such re-emerges; in the other, we have representations of feelings, etc. Only on the basis of the present can there be a feeling about these representations of feelings. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 251; 1927, p. 231)

4. “Lived experience” as murky edge

It [experiencing] is not at all vague in its being there. It may be vague only in that we may not know what it is. We can put only a few aspects of it into words. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 11)

The next attribute of lived experience [Erlebnis] is its qualitative being—it has a reality that cannot be defined by reflexive awareness, for it also extends into what is not possessed distinctly... can one say “possessed” here? ... I maintain that my lived experience [Erlebnis] also includes what is not distinct [nicht merklich] and needs to be explicated [ich kann es aufklären]. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 250; 1927, p. 230)

5. Inexhaustibility of “lived experience”

The completion of lived experience in the direction of the psychic nexus [psychischen Zusammenhang] is grounded in a lawful progression that always goes beyond the apprehended content of the lived experience. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 51; 1927, p. 29)

No other kind of value is contained in this process than that which is connected with the satisfaction of the act that captures the lived experience [Erlebnis] exhaustively. There is no volition here, but rather a being-pulled-along [Fortgezogenwerden] by the state of affairs itself to ever more constituent parts of the nexus and the satisfaction that lies in dealing with it exhaustively. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 50–1; 1927, p. 29)

As the individual engages in focusing, and as referent movement occurs, he finds himself pulled along in a direction he neither chose nor predicted. There is a very strong impelling force exerted by the direct referent just then felt. (Gendlin, 1964, p. 123)

This progression is conditioned by the state of affairs, and every step in it involves a satisfaction repeatedly instigated by the dissatisfaction [die immer wieder vom Ungenüge abgelöst wird] stemming from the inexhaustibility [Unerschöpflichkeit] of the lived experience. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 51; 1927, p. 29)

Any aspect of experiencing has very complex "unfinished” orders. Whatever way it may already be symbolized, it also provides the possibility for very many other symbolizations to occur. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 27–8)

No matter how finely we have already symbolized and differentiated it, the meanings in any aspect of experiencing are potentially so many that we cannot exhaust them. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 28)

Often, as they [clients] refer to it [experiencing] and talk about it, the conceptualization they did have becomes insufficient as more experiencing arises. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p.235)

Some of the quotations herein were applied to a discussion of verbatim transcripts of Focusing sessions. For more information, see our co-authored paper, “The experiencing model: saying what we mean in the context of Focusing and psychotherapy” (Ikemi, Okamura & Tanaka, 2023, pp. 54–6).

6. Progression of “lived experience”

... the resulting symbolization does symbolize the original felt meaning. In another sense it specifies it, adds to it, goes beyond it, or reaches only part of it—in short, changes it. We are concerned with just this double sense: it somehow accurately symbolizes the original felt meaning while at the same time it somehow also changes it. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 120)

... the other side of the process in which the psychic nexus is grasped as an object is the progression toward apprehensions of the lived experience that bring what is contained in it to more adequate, more stable, and more fundamental expression. And that is also the basis of the double relationship of the adequate representation of lived experiences and of the transcendence that originates in apprehension. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 51–2; 1927, p. 30)

7. Contrast between “logical concepts” and “the expression of lived experience”

Understanding will differ in kind and scope in relation to different classes of manifestations of life [Lebensäußerungen]. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 226; 1927, p. 205)

The first of these classes consists of concepts, judgments, and larger thought-formations. As constituents of science, they have been detached from the lived experience [Erlebnis] in which they arose, and they possess the common basic trait of having been adapted to logical norms. This gives them a selfsameness independent of their position in the context of thought. A judgment asserts the validity of what is thought independently of changes in the way it arose, whether the difference be that of the time or the people involved. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 226; 1927, p. 205)

The original phrase in the above “larger thought-formations” is “größere Denkgebilde,” a literal translation. However, Gendlin deliberately translated the phrase as “explicit formulations of thought” (Gendlin, 1950, p. 34). His translation seems to me to evoke his later philosophy.

Thus a judgment is the same for the person who formulates it and the one who understands it; it is, as it were, transported unchanged from the possession of the speaker to the one who understands it. This defines what characterizes the understanding of every logically perfect system of thought. Here understanding is directed at the mere logical content, which remains identical in every context, and is more complete than in relation to any other manifestation of life. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 226–7; 1927, pp. 205–6)

We are employing the term “logical" to apply to uniquely symbolized concepts. A “logical relationship" is one that is entirely in terms of uniquely specified concepts. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 141)

At the same time, however, such understanding does not disclose how the logical content that has been thought is related to the dark background [dunklen Hintergrund] and the fullness of psychic life [Fülle des Seelenlebens]. There is no indication of the peculiarities of the life from which it arose, and it follows from its specific character that it does not set up any expectation to go back to any psychic nexus. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 227; 1927, p. 206)

It is quite different with the expression of lived experience [Erlebnisausdruck]. A special relation exists between it, the life [Leben] from which it stems, and the understanding [Verstehen] that it brings about. ... An expression of lived experience ... draws from depths not illuminated by consciousness. But at the same time, it is characteristic of the expression of lived experience that its relation to the spiritual or human content expressed in it can only be made available to understanding within limits. Such expressions are not to be judged as true or false but as truthful or untruthful. For here dissimulation, lying, and deception sever the relation between the expression and the spiritual meaning expressed. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 227; 1927, p. 206)

The original word in the above “truthful[ness]” is “Wahrhaftigkeit.” However, Gendlin translated the word as “authentic[ity]” (Gendlin, 1950, p. 45). Later, Gendlin preferred the term “authenticity” (Gendlin, 1999), so we might recall the passage above from Dilthey (as well as Heidegger’s Eigentlichkeit) when Gendlin used the term.

8. Non-logical concepts as an expression of lived experience

Now if we use concepts to highlight something in life, then these serve first of all to describe life’s singularity. These general concepts, therefore, serve to express the intelligibility of life. Here there is only a loose relationship in progressing from what is presupposed to what comes next: what is new does not follow formally from the presupposition. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 254; 1927, p. 234)

The use of words is not arbitrary, but it is not governed or limited by logical patterns. ... Logical patterns are implicit in all human life, but they carry forward, they do not limit like premises ... Anything we study is thereby formally opened to being carried forward in other ways. (Gendlin, 1997b, pp. 395–6; 2018, pp. 265–6)

9. Music as an expression of lived experience

... there is a wider sense in which music too is the expression of lived experience. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 242; 1927, p. 221)

Tone follows upon tone and aligns itself with it according to the laws of our tonal system. This system leaves open infinite possibilities, but in the direction of one of these possibilities, tones proceed in such a way that earlier ones are conditioned by subsequent ones. ... Everywhere free possibility. Nowhere in this conditioning is there necessity. ... There is a having-to-be-thus in this sequence—it involves not necessity but rather the actualization of an aesthetic value. We should not think that what follows at a certain point could not have gone differently. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 241–2; 1927, p. 221)

No musical history could say anything about the way in which lived experience [Erlebnis] becomes music. The highest achievement of music is that what proceeds dimly [dunkel], indeterminately [unbestimmt], in a musical soul, and often imperceptibly [nicht merklich] to itself, unintentionally finds a crystal-clear expression in a musical form. ... there is no determinate path from lived experience [Erlebnis] to music. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 242; 1927, p. 222)

10. “Explication” in a non-parallel sense

In “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning,” Gendlin used the term “explication” in a parallel sense and the term “comprehension” in a non-parallel sense.

The comprehensive formulation changes the original felt meaning to some extent. It “comprehends” it, rather than being an identical parallel explication of it. (Gendlin, 1962, p. 123)

But, in his later works, he began to use the term “explication” in a non-parallel sense, as in comprehension, as “richer, more explicit, more fully known” (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 120) as follows:

We cannot—in words—copy, represent, or picture what we concretely had as felt meaning. ... Rather, to explicate is always a further process of experiencing. It carries forward what we directly felt. (Gendlin, 1965/66, p. 132)

Thus, I consider that the usage in his later works is closer to the meaning of “explication” in Dilthey’s quote below:

I must seek out an expression that can occur in time and is not distorted from without. Instrumental music is one such expression. However it may have originated, it presents a sequence in which the creator can survey its temporal nexus from one formation to another. Here we see a tendency that is directed, an action reaching out for fulfillment, an advance of psychic activity itself, a being conditioned by the past and yet the containment of various possibilities, an explication that is at the same time creative [Explikation, die zugleich Schaffen ist]. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 251-2; 1927, pp. 231-2)

After all, the term that corresponds to Dilthey’s “explication” is “comprehension” rather than “explication” in Gendlin’s earlier work “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning” as follows:

While a comprehension symbolizes the given experienced meaning, it can't help but be creative also. (Gendlin, 1962, p., 124)

11. Creativity of “expression”

Dilthey is still not appreciated today. He brought creativity into my problem. (Gendlin, 1989, p. 405)

... the scope of conscious life rises like a small island from inaccessible depths. But an expression [Ausdruck] can tap these very depths. It is creative. Thus in understanding [Verstehen], life [Leben] itself can become accessible through the recreation of creation. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 241; 1927, p. 220)

12. Determinate-indeterminate nature of words

What is given here is a sequence of words. Each of these words is determinate-indeterminate [bestimmt-unbestimmt]. It encompasses a range of meanings. The means of syntactically relating these words to each other are, also, ambiguous, within fixed limits; sense emerges when the indeterminate is determined by a construction. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 240–1; 1927, p. 220)

... understanding advances from a characteristic already grasped to a new one that can be understood on its basis. This inner relationship consists in the possibility of re-creating or re-experiencing [Nacherlebens]. This is the general method as soon as understanding leaves the sphere of words and their sense and does not look for the sense of signs but for the much deeper sense of a manifestation of life. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 254; 1927, p. 234)

The same symbolization (one set of verbal symbols) may have quite different meanings, and quite different degrees of meaning, if different felt meanings function “from out of which” this one symbolization is understood. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 129–30)

The greater the inherent distance between a given manifestation of life and the one who seeks to understand it, the more frequently uncertainties will arise. Then an attempt is made to overcome them. A first transition to higher forms of understanding occurs when understanding departs from the normal connection between an expression and the meaning content expressed in it. When the result of understanding presents an inner difficulty or something contradictory to what is otherwise familiar, we are forced to reconsider. (Dilthey, 2002, p. 231; Dilthey, 1927, p. 210)

13. Hermeneutic circle between the part and the whole

The meaning of the parts is not fixed; they must grow in meaning. With our terms we can articulate this. A hermeneutic circle would be vicious and impossible if we could think only with distinctions, parts, units, factors, patterned facts, formed things. We could only combine the individuated units that we already understand. (Gendlin, 1997b, p. 399; 2018, p. 269)

The whole of a work is to be understood from the individual words and their connections with each other, and yet the full understanding of the individual part already presupposes that of the whole. (Dilthey, 1996, p. 249; 1924, p. 330)

From the particular the whole, from the whole again the particular. Moreover, the whole of a work demands moving on the individuality <of the author>, and to the literature to which it stands in relation. ... Thus understanding derives from the whole, whereas the whole derives from the particular. (Dilthey, 1996, p. 253; 1924, p. 334)

The simplest case in which meaning arises is the understanding of a sentence. Each individual word has a meaning, and we derive the sense of the sentence by combining them. We proceed so that the intelligibility of the sentence comes from the meaning of individual words. To be sure, there is a reciprocity between whole and parts by virtue of which the indeterminacy of sense, namely, the possibilities of sense, <are established> in relation to individual words. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 254–5; 1927, p. 235)

Just as words have a meaning [Bedeutung] by which they designate something, and sentences have a sense [Sinn] that we construe, so we can construe the connectedness of life from the determinate-indeterminate meaning of its parts. Meaning is the special relation that the parts have to the whole within life. (Dilthey, 2002, pp. 253–4; 1927, pp. 233–4)

14. Better understanding

Dilthey held that we never really have the same understanding as the author had. If we understand a work at all, we understand it better than its author did. We must create the author's process out of our own, thereby augmenting both. (Gendlin, 1997b, p. 399; 2018, p. 269)

The ultimate goal of the hermeneutic process is to understand an author better than he understood himself. This is a principle that is the necessary consequence of the theory of unconscious creation. (Dilthey, 1996, p. 250; 1924, p. 331)

The interpretation of poets is a special task. The rule ... to understand an author better than he has understood himself also allows us to solve the problem of the idea in poetry. This idea is (not present as an abstract thought, but) as an unconscious nexus that is operative in the organization of the whole and on the basis of which inner form is understood. A poet does not need to be conscious of the idea and will never be fully conscious of it. The interpreter brings it into relief and this is perhaps the highest triumph of hermeneutics. (Dilthey, 1996, p. 255; 1924, p. 335)

15. Difference in terminology definition: “content”

There are terms that Dilthey uses positively, Gendlin uses negatively, and vice versa. For example, let’s look at the term “content” here.

Dilthey does not use “content” negatively when discussing the primordial qualities of lived experience.

Every lived experience contains a content. By content we here understand not all the parts contained in an encompassing whole that could be separated from this whole in thought. So understood, the content would be the sum total of what can be differentiated from what is contained in the lived experience as if it were an enclosing container. Rather, only a part of what is distinguishable in a lived experience is here designated as content. (Dilthey, Dilthey, 2002, p. 40; 1927, pp. 19-20)

But Gendlin uses the term content rather negatively, in the sense that it can be separated from the whole in thought as if it were an enclosing container.

The preconceptual is not constituted of actual defined existent contents or meanings. ... All these meanings "exist” in a sense, but it is not the sense of marbles in a bag. These "implicit" meanings are not complete and formed (under cover, as it were). (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 28)

Gendlin uses the word “content” only when describing the characteristics of a later countable unit experience, and he does not say that the primordial uncountable experiencing consists of contents:

"Experiencing” ... is capable of many different conceptualizations, but is not itself explicit conceptual contents of such conceptualizations. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 243)

It should be noted that Gendlin did not take over Dilthey’s work on the detailed definition of the term “content.”

Unsolved problems

The above is my attempt to determine where Dilthey positively influenced Gendlin. However, some things that Gendlin often states that he owes to Dilthey have unclear sources. For example, “... Wilhelm Dilthey could assert that, in principle, any human expression is understandable, no matter how unique” (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 198) or “... as Dilthey argued, every experiencing is already inherently also an understanding (Dilthey 1927)” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, pp. 45–6). The former was discussed in my other blog post, “Joachim Wach: the forgotten man behind Gendlin’s understanding of Dilthey.” The latter was discussed in my further blog post, “Gendlin's ‘focaling’ and Dilthey’s ‘purposiveness.’”

Note

[*1] There is currently no established theory as to why Gendlin adopted the new translation of the English word “experiencing” to refer to the process or functioning. The following is only my hypothesis:

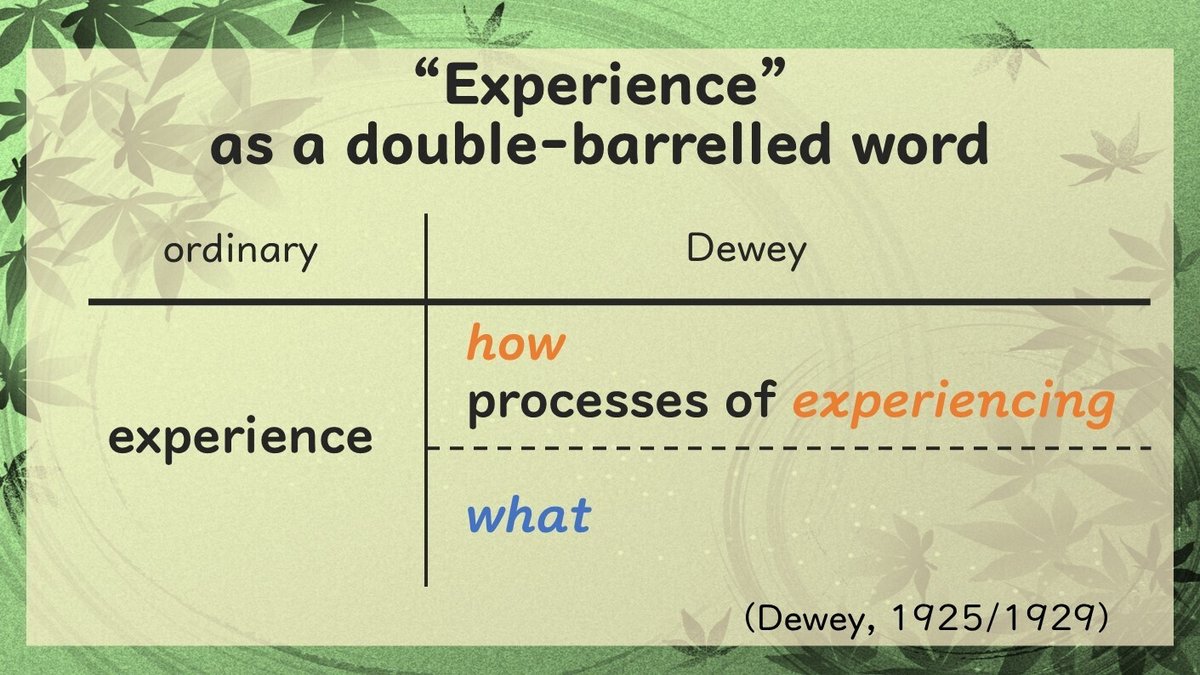

In addition to merely distinguishing the meanings of the two similar terms “Erleben” and “Erlebnis” in German, I see that Gendlin may have referred to Dewey’s idea of “experience” as “a double-barrelled word” when he separated them in his English translations. In other words, experience has a “how” and a “what” meaning; the “how” is characterized as a “process” and can be expressed in the “ing” form:

We begin by noting that “experience” is what James called a double-barrelled word. Like its congeners, life and history, it includes what men do and suffer, what they strive for, love, believe and endure, and also how men act and are acted upon, the ways in which they do and suffer, desire and enjoy, see, believe, imagine—in short, processes of experiencing. (Dewey, 1925/1929, p. 8 [LW 1, 18]; cf. McKeon, 1953/1998, p. 225)

[*2] Gendlin did not adopt the conventionally used English translation of “lived experience” in the context of Dilthey’s philosophy.

References

Dewey, J. (1925/1929). Experience and nature (2nd ed.). Open Court. Reprinted as Dewey, J. (1981). The later works, vol. 1 [Abbreviated as LW 1]. Southern Illinois University Press.

Dilthey, W. (1996). The rise of hermeneutics (translated by F. R. Mameson & R. A. Makkreel). In Hermeneutics and the study of history (edited by R. A. Makkreel, & F. Rodi, Selected works / Wilhelm Dilthey, Vol. 4, pp. 235–58). Princeton University Press. Originally published as Dilthey, W. (1924). Die Entstehung der Hermeneutik. In Abhandlungen zur Grundlegung der Geisteswissenschaften (Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 5, pp. 317–38). B.G.Teubner.

Dilthey, W. (2002). The formation of the historical world in the human sciences (edited by R. A. Makkreel, & F. Rodi) (Selected works / Wilhelm Dilthey, Vol. 3). Princeton University Press. Originally published as Dilthey, W. (1927). Der Aufbau der geschichtlichen Welt in den Geisteswissenschaften (Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 7). B.G.Teubner.

Gendlin, E. T. (1950). Wilhelm Dilthey and the problem of comprehending human significance in the science of man. MA Thesis, Department of Philosophy, University of Chicago.

Gendlin, E. T. (1962/1997). Experiencing and the creation of meaning: a philosophical and psychological approach to the subjective (Paper ed.). Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1964). A theory of personality change. In P. Worchel & D. Byrne (eds.), Personality change (pp. 100-48). John Wiley & Sons.

Gendlin, E.T. (1965/66). Experiential explication and truth. Journal of Existentialism, 6, 131-146.

Gendlin, E. T. (1989). Phenomenology as non-logical steps. In E. F. Kaelin, & C. O. Schrag (Eds.) American phenomenology: origins and developments (Analecta Husserliana, Vol. 26) (pp. 404–410). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Gendlin, E. T. (1997a). How philosophy cannot appeal to experience, and how it can. In D.M. Levin (Ed.), Language beyond postmodernism: saying and thinking in Gendlin’s philosophy (pp. 3–41 & 343). Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1997b). The responsive order: a new empiricism. Man and World, 30(3), 383–411.

Gendlin, E.T. (1999). Authenticity after postmodernism. Changes. An International Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy, 17(3), 203-212.

Gendlin, E. T. (1997/2018). A process model. Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (2002). Foreword. In C.R. Rogers & D.E. Russell, Carl Rogers: The quiet revolutionary. An oral history (pp. XI–XXI). Penmarin Books.

Gendlin, E. T. (2018). Saying what we mean: implicit precision and the responsive order (edited by E. S. Casey & D. M. Schoeller). Northwestern University Press.

Ikemi, A., Okamura, S., & Tanaka, H. (2023). The experiencing model: saying what we mean in the context of Focusing and psychotherapy. In Eric Severson & Kvin Krycka (eds.), The psychology and philosophy of Eugene Gendlin: making sense of contemporary experience (pp. 44–62). Routledge.

Makkreel, R. A. (1992). Dilthey: philosopher of the human studies (2nd edition). Princeton University Press.

McKeon, R. (1953/1998) Experience and metaphysics. In Philosophy, science, and culture (Selected writings of Richard McKeon, v. 1, pp. 222-8). University of Chicago Press.

Mimura, N. (2015). Gendlin’s early philosophy and the theory of experiencing (Philosophy that continues to question experience, Vol. 1) [in Japanese]. ratik.

Hideo Tanaka (2004–5). A bibliographical survey of E.T. Gendlin’s early theory of experiencing: influences of W. Dilthey’s philosophy on his psychotherapeutic studies, Part 1 & 2 [in Japanese, English summary & table of contents]. Bulletin of Meiji University Library, 8, 56–81 & 9, 58–87.