History of Chapters II and I Use of the Term “Implying” in “A Process Model”: with reference to Mead and Dewey

In “A Process Model” (Gendlin, 1997/2018), the basic term “implying” is used frequently. This term was first used in his earlier published papers (Gendlin, 1973a; 1973b). It is my view at this stage that the various uses of “implying” developed along the following historical lines: First, in the early 1970s, Gendlin began the “bringing or generating time” use of implying corresponding to Chapter II of APM. Next, in the late 1980s, he started the “horizontal” use of implying corresponding to Chapter I of “A Process Model” (APM). Finally, the other uses of implying were formulated with the writing of APM.

Preliminary history of Chapter II usage of implying

In his earlier paper “A theory of personality change” (Gendlin, 1964), “hunger” and “eating” were discussed as follows, but the term “implying” had not yet been introduced:

This [hunger's] sensation certainly "means" something about eating, but it does not "contain" eating. To be even more graphic, the feeling of hunger is not a repressed eating. (Gendlin, 1964, p. 114)

So, let us first review the discussion of “hunger” and “eating” by classical pragmatist George H. Mead, followed by a look at how Gendlin presented the term “implying” in 1973.

In the ox there is hunger, and also the sight and odor which bring in the food. The whole process is not found simply in the stomach, but in all the activities of grazing, chewing the cud, and so on. This process is one which is intimately related to the so-called food which exists out there. (Mead, 1934, pp. 130-1)

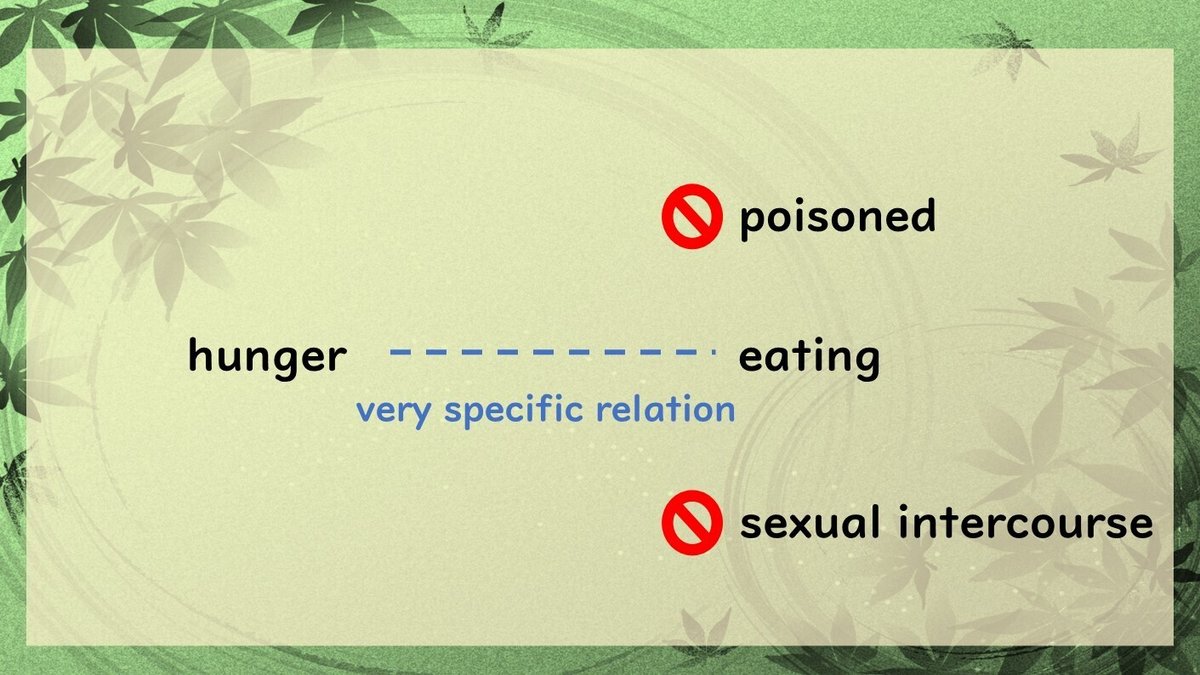

Thus, “hunger” is somehow related to “eating,” and “eating” is somehow related to “food.” Gendlin continues Mead’s argument by asserting that this relation is “a very specific relation” that is different from others:

For example, between hunger and eating there is a change, but this isn't just any kind of change, as from hunger to being poisoned, or being temporarily shifted to pain, flight, anxiety, or sexual intercourse. Eating thus has a very specific relation to being hungry, although it is certainly a change. (Gendlin, 1973b, p. 325)

He then suggested calling the continuity between “hunger” and “eating” by the verb “to imply.”

Any moment of bodily living thus “implies” or tends toward further living, but not just anything one pleases, only just certain different looking steps. There is a bodily felt continuity in these steps, it doesn't require a biologist to sense that eating is what follows hunger, that exhaling is what is implied when one holds one's breath .... (Gendlin, 1973b, p. 325)

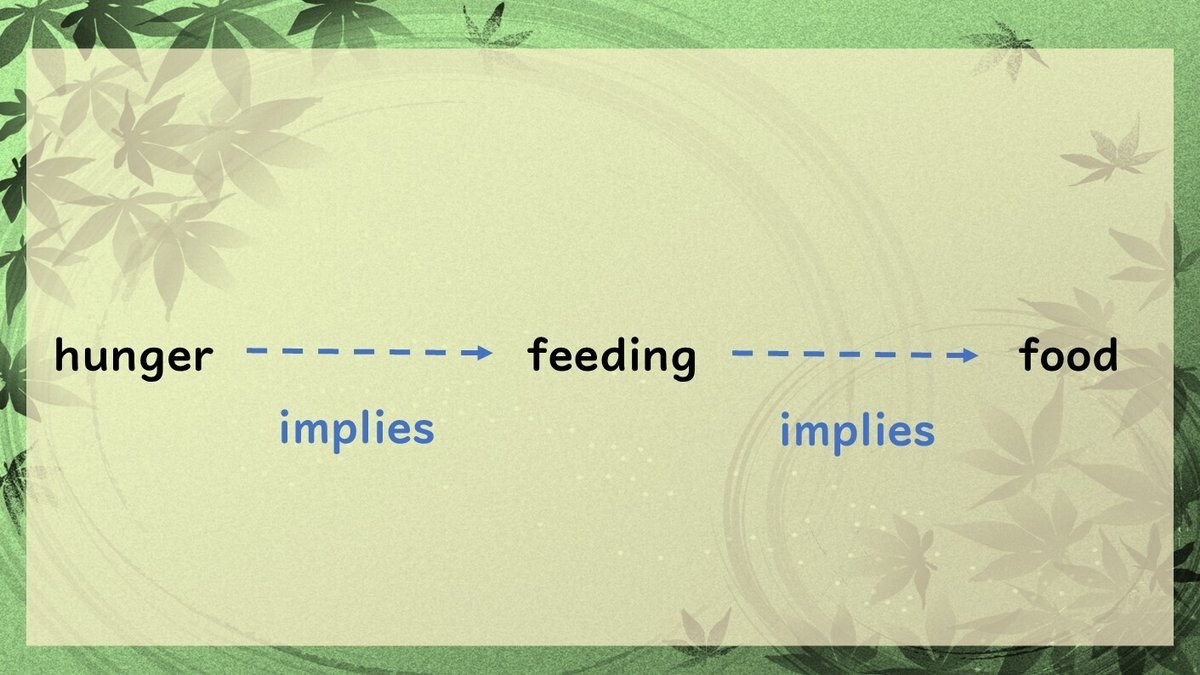

He then began to use “imply” as a verb, linking not only hunger and eating but also eating and food.

The body implies not only the many behaviors not now going on, but also the environments in and with which these implied behaviors can occur. For example, if feeding is implied, that implies food. If burying feces is implied, that implies a scratchable ground. ... The "interactional" aspect of the body is that its implied behaviors also imply the environment. (Gendlin, 1973a, pp. 372-3)

The discussion in this passage almost anticipates the following usage in Chapter II of APM:

“I say that hunger implies feeding, and of course it also implies the en#2 that is identical with the body. Hunger implies feeding and so it also implies food.” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 9)

Moreover, the idea, corresponding to the title of Chapter II, that implying is functionally a “cycle” was already discussed in his ’73 paper:

When, in biology, functional systems are considered, it is clear that "hunger," for example, ... leads to feeding behavior and perhaps also to hunting, tracking, killing, tearing, chewing, defecating, scratching the ground and burying feces, resting, and also getting hungry again. I want to use the word "implies" here. I want to say that when hungry, the body "implies" tracking, feeding, defecating, that feeding "implies" scratching the ground to bury feces, and so on. (Gendlin, 1973a, pp. 371-2)

Here, “imply” is used as a verb that connects activities, as “tracking” implies “feeding” and “feeding” implies “scratching the ground.” This usage is carried over directly to “a string of en#2s” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 9) in Chapter II of APM.

As mentioned above, about the terminology of “implying,” Gendlin began his consideration of the term in the early ’70s from the kind of “bringing or generating time” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 29) usage that was later represented in Chapter II of APM.

The relationship between “hunger” and “eating” corresponds to the relationship between “need” and “satisfaction” if we were to go back to conventional terminology in philosophy and psychology. John Dewey, another classical pragmatist, for example, argues that “By need is meant a condition of tensional distribution of energies such that the body is in a condition of uneasy or unstable equilibrium” and “By satisfaction is meant this recovery of equilibrium pattern, consequent upon the changes of environment due to interactions with the active demands of the organism” (Dewey, 1925/1929, p. 253 [LW 1, 194]). Gendlin adds a new page to conventional philosophy by moving from the static usage of need and satisfaction to a more dynamic consideration by introducing the “bringing or generating time” usage of “implying”:

We can try out saying that eating satisfies hunger, that it carries out what hunger implies, that eating carries the hunger into some sort of occurring. Hunger is the implying of eating (the “need” for food we say, making a noun out of this implying). Then eating is the satisfaction (another noun). The nouns make separate bits out of the process. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, pp. 10-1)

Preliminary history of Chapter I usage of implying

When Dewey speaks of “interaction,” he rejects the traditional idea that the organism inside the skin and the environment outside the skin are a priori independent and self-existent and that only then do they interact in both directions.

The thing essential to bear in mind is that living as an empirical affair is not something which goes on below the skin-surface of an organism: it is always an inclusive affair involving connection, interaction of what is within the organic body and what lies outside in space and time, and with higher organisms far outside. (Dewey, 1925/1929, p. 282 [LW 1, 215])

This consideration of Dewey was taken over by Gendlin after the late ’70s:

The body ... is the bigger system of ongoing living with others. It is not just within the skin-envelope.” (Gendlin, 1978, p. 343).

... what we call “the body” is a vastly larger system. “The body” is not only what is inside the skin-envelope” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 27).

Dewey’s idea that the two interacting are integrated into one has appeared in Gendlin’s writings after the early ’80s.

The processes of living are enacted by the environment as truly as by the organism; for they are an integration. (Dewey, 1938, p. 25 [LW 12, 32])

The body is both environment and living process. Every cell is both, and again every part of a cell. Body and environment are one system, one thing, one event, one process. (Gendlin, 1984, p. 99)

Body and en are one event, one process. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 4)

Whatever else organic life is or is not, it is a process of activity that involves an environment. It is a transaction extending beyond the spatial limits of the organism. An organism does not live in an environment; it lives by means of an environment. (Dewey, 1938, p. 25 [LW 12, 32])

What “inside” and “in” mean is no simple question. The simple “in” of a skin-envelope assumes a merely positional space in which a line or plane divides into an “outside” and an “in.” ... The body is in the environment but the environment is also in the body, and is the body. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 7)

Let us discuss more specifically how they are integrated into one. Dewey thought that there is first the life activity of “walking,” which is secondarily separated into the “ground” walked upon and the “legs” walking:

Life denotes a function, a comprehensive activity, in which organism and environment are included. Only upon reflective analysis does it break up into external conditions - air breathed, food taken, ground walked upon - and internal structures - lungs respiring, stomach digesting, legs walking. (Dewey, 1925/1929, p. 9 [LW 1, 19])

Gendlin began considering an example of walking in which the two are not separated in the late ’80s.

If you are a land animal, the ground you walk on is part of how your feet are built, and not only your feet. The muscles up into your thighs, your posture, and the whole balance of all your organs already include the ground against which you press when you walk. The sensation and internal feel-quality of all your organs and muscles comprehend how you walk on solid earth. Your walking-pattern is implied in the feel of your whole body. (Gendlin, 1986, p. 143)

The ‘implying’ in the quote above differs from the ‘bringing or generating time’ usage in the 70s. This usage, which has been used since the ’80s, prepared the way for the later “horizontal” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 29) use of implying in Chapter I of APM.

The en#2 is not the separable environment but the environment participating in a living process. The en#2 is not the ground, but the ground-participating-in-walking, its resistance. The behavior cannot be separate from this ground-participating. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 4)

Body and en#2 imply each other... They are not look-alikes. The mutual implying between body and environment is “non-iconic,” that is to say nonrepresentational. The muscles and bones in the foot and leg do not look like the ground, but they are very much related. One can infer hardness of the ground from the foot, the leg, and their muscles. In an as-yet-unclear way “one can infer” means that the foot implies the ground’s hardness. Other kinds of terrain or habitat imply different body parts. Since the body and the en are one event in en#2, each implies the other. They imply each other in that they are part of one interaction process, one organization. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 5)

“Body and en#2 are one event; each implies the whole event.” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 29)

The other uses of implying

As described above, I consider that Gendlin developed the idea of implying in the ’70s and ’80s, inheriting and modifying Mead’s and Dewey’s perspectives on the interaction of organisms with their environment. However, as organized in the section “(d-1) Symbolic functions of the body” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 29), the uses of implying in APM are not limited to the uses in Chapters II and I. In particular, the uses first mentioned in Chapter IV-A are not discussed in detail in his writings before APM. I consider that the other uses were finally formulated with the writing of APM.

References

Dewey, J. (1925/1929). Experience and nature (2nd ed.). Open Court. Reprinted as Dewey, J. (1981). The later works, vol. 1 [Abbreviated as LW 1]. Southern Illinois University Press.

Dewey, J. (1938). Logic: the theory of inquiry. Henry Holt. Reprinted as Dewey, J. (1986). The later works, vol. 12 [Abbreviated as LW 12]. Southern Illinois University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1964). A theory of personality change. In P. Worchel & D. Byrne (Eds.), Personality change (pp. 100-48). John Wiley and Sons.

Gendlin, E.T. (1973a). A phenomenology of emotions: Anger. In D. Carr & E.S. Casey (Eds.), Explorations in phenomenology (pp. 367-98). Martinus Nijhoff.

Gendlin, E.T. (1973b). Experiential psychotherapy. In R. Corsini (Ed.), Current psychotherapies (pp. 317-52). Peacock.

Gendlin, E.T. (1978). The body’s releasing steps in the experiential process. In J.L. Fosshage & P. Olsen (Eds.), Healing. Implications for psychotherapy (pp. 323-49). Human Sciences Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1984). The client’s client: the edge of awareness. In R.L. Levant & J.M. Shlien (Eds.), Client-centered therapy and the person-centered approach: new directions in theory, research, and practice (pp. 76-107). Praeger.

Gendlin, E.T. (1986). Let your body interpret your dreams. Chiron.

Gendlin, E. T. (1997/2018). A process model. Northwestern University Press.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. (edited by C.W. Morris). University of Chicago Press.