Gendlin’s “reversal” and the history of metaphor theories—Richards, Black, and Merleau-Ponty

In his paper on the theory and practice of Focusing, Akira Ikemi discussed the order in which a metaphorical expression and the similarities, likenesses, or commonalities between the things being compared within the expression are presented as follows:

In contrast to conventional theories of metaphor where the similarity of the situation and the metaphor is assumed to be primary, in Gendlin’s metaphor theory, the similarity is found after the carrying forward (Gendlin, 1995; Okamura, 2016). (Ikemi, 2017, p. 168; cf. Thorgeirsdottir, 2023, p. 98)

Why did Gendlin insist on this order? I will begin my discussion by examining its historical background.

Reversal of the order: metaphor and similarity

In “A Process Model (APM)” (Gendlin, 1997/2018), the ideas formulated in “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning (ECM)” (Gendlin, 1962/1997) were applied and expanded in various ways. A typical example is his metaphor theory. Let us quote from APM:

It was long said that a metaphor is “based on” a preexisting similarity between two different things. In our model it is the metaphor that creates or specifies the similarity. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 50)

After discussing the above, he stated that “we reversed the order” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 51) by his earlier work, ECM. In Chapter IV of ECM, he presented “Reversal of the usual philosophic procedure” (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 140–4) and already stated as follows:

The likeness is creatively specified and symbolized by the metaphor. Particular likenesses [=similarities] can then be “found" or “created," as aspects of the metaphoric meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 142)

... the likenesses exist only as the new meaning is created. The likenesses do not create the new meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 142–3)

However, assuming that Gendlin alone conceived of the reversal would be dangerous and erroneous. Therefore, let us trace how earlier thinkers or philosophers prepared the “reversal” and how he developed the argument.

Prehistory of the reversal: Richards and Black

The English literary critic and thinker Ivor A. Richards (1893–1979), in his classic masterpiece “The Philosophy of Rhetoric,” specifically discussed metaphor as follows:

Let me begin now with the simplest, most familiar case of verbal metaphor—the leg of a table for example... Now how does it differ from a plain or literal use of the word, in the leg of a horse, say? The obvious difference is that the leg of a table has only some of the characteristics of the leg of the horse. A table does not walk with its legs; they only hold it up and so on. In such a case we call the common characteristics the ground of the metaphor. Here we can easily find the ground, but very often we cannot. A metaphor may work admirably without our being able with any confidence to say how it works or what is the ground of the shift. (Richards, 1936, p. 117)

The “common characteristics” referred to here as the “ground” is what has long been called in Latin “tertium comparationis” (the third [part] of the comparison). In insisting that metaphors can work without being able to say what the common characteristics are, Richards can be said to be one who prepared Gendlin’s “reversal.” What is unfortunate, however, is that Richards called the characteristics the “ground.” Contrary to the discussion above, this naming gave the impression that the common characteristics had been explicitly stated beforehand and that the metaphor could only work based on the explicit characteristics. Such an impression is at odds with the “reversal.”

Richards’ discussion was called “an interaction view of metaphor” (Black, 1955, p. 285; 1981, p. 72) by an analytic philosopher in the English-speaking world, Max Black (1909–1988). Black saw himself as belonging to this lineage and took over and developed the view. Three years before Gendlin wrote his doctoral dissertation (Gendlin, 1958) as the original ECM, Black had already argued as follows:

... the metaphor creates the similarity than to say that it formulates some similarity antecedently existing. (Black, 1955, p. 285; 1981, p. 72; cf. Johnson, 1987, p. 69)

In this way, Black further prepared Gendlin’s “reversal” by making Richards’ argument thorough.

Prehistory of the reversal: Merleau-Ponty

I would also like to mention Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) as a French philosopher who prepared Gendlin’s “reversal” without the influence of Richards or Black.

Merleau-Ponty often discussed reports of a patient who suffered brain damage during World War I, known as Schneider. In his seminal work, “Phenomenology of Perception,” he discussed a case in which Schneider could not understand metaphors and analogies. In my view, this discussion is very helpful in understanding the contrast between “the usual philosophic procedure” and “the reversal of the procedure” through concrete examples.

Merleau-Ponty summarized Schneider’s case based on the report in Benary (1922):

... he cannot understand, in their metaphorical sense, such common expressions as ‘the chair leg’ or ‘the head of a nail’, although he knows what part of the object is indicated by these words. (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 128; cf. 1945, p. 149)

This means that contrary to Richards’ assumption, such metaphors do not work in this patient’s case.

... the patient does not understand even such simple analogies as: ‘fur is to cat as plumage is to bird’, or ‘light is to lamp as heat is to stove’, or ‘eye is to light and colour as ear is to sounds.’ (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 128; cf. 1945, p. 148)

... the patient manages to understand only when he has made it explicit by recourse to conceptual analysis. ... he thinks about the analogy between eye and ear and clearly does not understand it until he can say: ‘The eye and the ear are both sense organs, therefore they must give rise to something similar.’ (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 128; cf. 1945, p. 148)

In other words, metaphors and analogies do not work at all for the patient until he makes explicit the common characteristics, such as “… both sense organs.”

On the other hand, regarding the normal subjects, he discussed as follows:

In normal thought eye and ear are immediately apprehended in accordance with the analogy of their function.... (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, pp. 128-9; cf. 1945, p. 149)

This means that the analogy can work without going through the “roundabout way” (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 128; cf. 1945, p. 149) of the explicit characteristics— “tertium comparationis” (Benary, 1922, p. 263; Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 128; cf. 1945, p. 148).

According to Gendlin’s metaphor theory, the patient’s thinking process follows “the usual philosophic procedure,” whereas the normal subject’s thinking process follows “the reversal of the procedure.” Thus, I consider Merleau-Ponty to be one of those who prepared Gendlin’s “reversal.”

Succession and development by Gendlin

Following his predecessors, Gendlin discussed the writing process of the poet (possibly Scottish poet Robert Burns) who created the metaphoric line “My love is like a red, red rose” in ECM. Usually, when examining such creative processes, “The old philosophic procedure tempts us” that “The likeness to ‘red, red rose’ appears to determine just what aspect of ‘my love’ will be newly created by the metaphor” (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 142). But we should reverse the procedure, he argued:

The first creator of the metaphor begins with his undifferentiated experience (of his girl), which the metaphor will help him specify. He specifies his experience by asking himself, “Now what is that like?” He, too, does not yet have the likeness at that point. He asserts that there is a likeness between something unspecified in his present experienced meaning (of the girl) and something (as yet not found) in his experience in general. When he finds it (a red, red rose) he has only then fully created the specific aspect of the experience of the girl. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 142)

The order is that the rose is first found as something implicitly similar to the lover before the characteristics are explicitly present as likenesses — “fresh, blooming, eventually passing, beautiful, living, tender, attractive, soft, quietly waiting to be picked, part of greater nature” (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 142).

Gendlin later summarized his theory of metaphor in his paper “Crossing and Dipping,” which offers a specific consideration as follows:

If one says “A cigarette is a time bomb” people can state the common feature. But, if one first asks them to write the main features of a cigarette—before hearing the time-bomb metaphor, they will not list that feature. (Gendlin, 1995, p. 559)

If the characteristics had been explicitly stated beforehand, we would have been able to mention them before hearing the metaphor. However, that was not the case, and the characteristics were only derived as common features after it was implicitly felt that a cigarette was somewhat similar to a time bomb.

The idea that features or traits were not explicitly present beforehand continued to be considered in APM:

By speaking of A as if it were B, certain aspects of A are made which were not there before as such. The metaphor does not “select” this trait from a list of existing traits of A; there is no such fixed set. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 50)

Applying the earlier cigarette example to the argument above, by speaking of a cigarette as if it were a time bomb, certain aspects of a cigarette are made which were not there before as such. The metaphor does not “select” this trait from a list of existing traits of a cigarette; there is no such fixed set.

Next, let us go back in time and consider the argument in ECM:

What is the new sort of “symbolization” between the symbols “a red, red rose" and the new aspect of the old experience: “my love”? ... It depends on the emergence of a new aspect of experience from past experience. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, p. 115)

In other words, we can ask: What is the new sort of “symbolization” between the symbols of B and the new aspect of the old experience of A? To put it further, we can also say that by speaking of “my love” as if it were “a red, red rose", certain aspects of “my love” are made which were not there before as such.

Let’s see how he discussed, with other examples, the characteristics or traits that emerge beyond any prior expectations when two things are crossed.

For example, how is your anger like a chair? (It just sits? It might get thrown at someone?) If you try it with your anger, what comes may be new. How does that work? You let all about chair interact with all about your anger and—something comes. Then you say it “was” always true of you. But actually it was made by crossing them just now. (Gendlin, 1986, p. 150)

The example above was discussed by Shimpei Okamura, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Gendlin’s theory of metaphor as follows:

If you fully feel your own anger and try to “cross” with the chair that happens to be in front of you to find similarities between it and your own anger, you may be able to name the features of your own feeling of anger, such as “sitting heavily,” “wanting to throw it at someone,” or “holding myself up tight.” It is important to note that these features of anger, as identified here, did not exist before crossing with the chair. It was only when one’s anger and the chair were crossed that the features became clear. Thus, the meaning of the metaphor is created after the metaphorical expression is used. (Okamura, 2016, p. 58)

A similar example is given in APM:

For example, you can cross toothbrushes and trains. Then you might say, “Yes, I see, a toothbrush has only one ‘car,’” or you might say “They both shake us,” or “It would be great to have my personal train.” (Gendlin, 1997/2018, p. 52)

Again, you can see that the features only became explicit after the toothbrushes were crossed with the trains.

Conclusion

Gendlin reiterated his metaphor theory even after ECM as follows:

A new theory of metaphor follows, if we open “metaphor” to itself. It makes/finds in a poetizing that is a dwelling in and beyond the old units. They do not trace through as pre-existent similarities, pre-existing respects of comparison, arrangements of fixed units. (Gendlin, 1988, p. 150)

The commonalities [likenesses] do not determine the metaphor. Rather, from the metaphor, and only after it makes sense, is a new set of commonalities derived. (Gendlin, 1995, p. 556)

Johnson and I agree that new metaphorical meanings are not derived from preexisting similarities, and that metaphors can be true. (Gendlin, 1997, p. 175)

Metaphors do not depend on preexisting likeness; rather, a metaphor creates a new likeness. In metaphors such a likeness is a new third [*1]. (Gendlin, 1997/2018, pp. 132–3)

Black explored the “reversal” of the order, but his discussion was limited to linguistic analysis in the tradition of analytic philosophy. Merleau-Ponty, on the other hand, extended the reversal to the preconceptual experience. Whereas Merleau-Ponty discussed only the hearer or reader’s processes of the metaphor, Gendlin extended his discussion to the speaker or writer’s processes of the metaphor (cf. Tanaka, 2023, August). Moreover, in APM, he applied this idea of the reversal to his discussion of the various stages of living processes, such as plants and animals.

Appendix: definition of metaphor in Gendlin

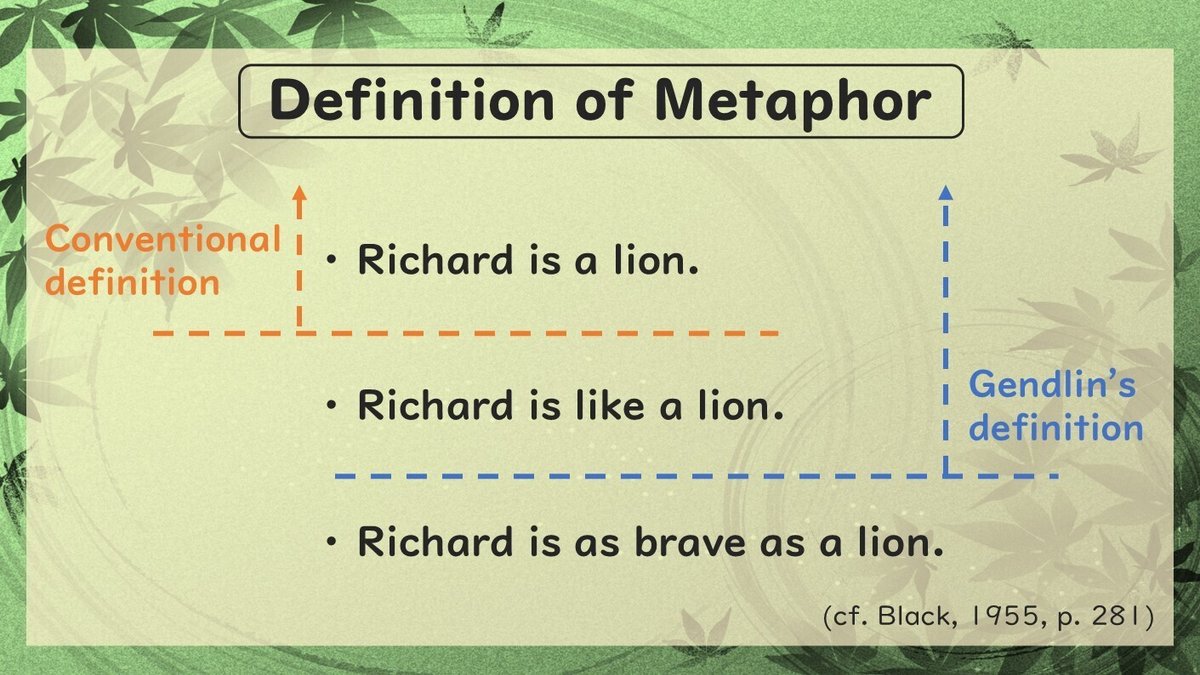

Metaphors are broader in meaning than metaphors in conventional rhetoric and linguistics when Gendlin discusses them.

First, the metaphors Gendlin discusses do not exclude “simile”:

Symbols that already have parallel felt meaning are put together in such a way that a new felt meaning is created and symbolized by them. This occurs to some extent in all creative thought, problem solving, therapy, and literature. Its epitome is a metaphor. We shall call this functional relationship "metaphor," using that term to include not only similes and the like, but also all creation and symbolization of new felt meaning. (Gendlin, 1962/1997, pp. 111–3)

In other words, it is essential whether commonalities such as “(they are) brave” exist beforehand, not whether “like” is included or not.

Second, the metaphors Gendlin discusses, unlike Roman Jakobson and Jacques Lacan, do not exclude “metonymy” either:

In hypnosis, for example, when the individual is told to “raise your hand," he will lift the palm of his hand up by his wrist. He will not, as when awake, interpret the idiomatic phrase appropriately (it means, of course, to raise one's whole arm up into the air). (Gendlin, 1964, pp. 140–1)

In this case, the individual can call it by Gendlin's definition that there is no “metaphor” functioning between the symbols “raise your hand” and the felt meaning. For more information on this point, please see another article below:

Very old (“primitive”) sequences in dreams and with hypnosis|Hideo TANAKA

Note

*1) If the metaphor “My love is like a red, red rose” creates likenesses such as “fresh, blooming, eventually passing, beautiful, living, tender, attractive, soft, quietly waiting to be picked, part of greater nature,” then such explicit likenesses can be called “new thirds” or “new third universals,” according to APM terminology.

References

Benary, W. (1922). Studien zur Untersuchung der Intelligenz bei einem Fall von Seelenblindheit. Psychologische Forschung, 2, 208-97.

Black, M. (1955). Metaphor. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 55(1), 273–94. Reprinted as Black, M. (1981). Metaphor. M. Johnson (ed.) Philosophical perspectives on metaphor (pp. 63–82). University of Minnesota Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1958). The function of experiencing in symbolization. Doctoral dissertation. University of Chicago.

Gendlin, E.T. (1962/1997). Experiencing and the creation of meaning: a philosophical and psychological approach to the subjective (Paper ed.). Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1986). Let your body interpret your dreams. Chiron.

Gendlin, E.T. (1988). Dwelling. In H.J. Silverman, A. Mickunas, T. Kisiel, & A. Lingis (Eds.), The Horizons of continental philosophy: essays on Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty (pp. 133-52). Kluwer Academic.

Gendlin, E.T. (1995). Crossing and dipping: some terms for approaching the interface between natural understanding and logical formulation. Minds and Machines, 5(4), 547-60.

Gendlin, E.T. (1997). Reply to Johnson. In D.M. Levin (Ed.), Language beyond postmodernism: saying and thinking in Gendlin’s philosophy (pp. 168–75 & 357–58). Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T. (1997/2018). A process model. Northwestern University Press.

Ikemi, A. (2017). The radical impact of experiencing on psychotherapy theory: an examination of two kinds of crossings. Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies, 16(2), 159–72.

Johnson, M. (1987). The body in the mind: the bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. University of Chicago Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, trans.). Humanities Press. Originally published as Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception. Gallimard.

Okamura, S. (2016). The creativity of wordplay: a consideration from Gendlin’s conception of ‘crossing’ [in Japanese]. Studies in Integral Humanities, 1, 55–63.

Richards, I.A. (1936). The philosophy of rhetoric. Oxford University Press.

Tanaka, H. (2023, August). Comprehension and Metaphor in “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning” (Gendlin, 1962/1997).

Thorgeirsdottir, S. (2023). Liberating language: Gendlin and Nietzsche on the refreshing power of metaphors. In E. Severson & K. Krycka (eds.), The psychology and philosophy of Eugene Gendlin: making sense of contemporary experience (pp. 85–101). Routledge.