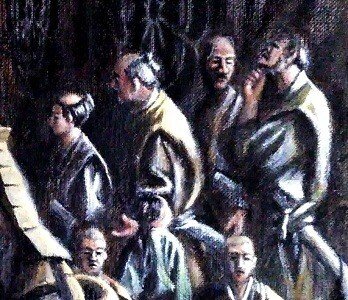

Shoko —Nagoya, 14 May 1552

Oil on canvas, 65×80cm, 2008-2021, M.Tsushima

The Shoko is one of the most iconic moments in Nobunaga's early years. Nobunaga, at the age of seventeen, was at that time called "a fool", and at his father's funeral, he did shoko (burning incense) in the most foolish manner.

Background

Nobunaga's father, Oda Nobuhide, died at the age of 41. Nobunaga held a funeral ceremony at the Banshoji Temple in Nagoya.

In a Buddhist funeral ceremony, a participant in front of an altar picks up a pinch of incense powder and puts it in a bowl of smouldering incense. It is called shoko meaning "burning incense".

Nobunaga did shoko in an extraordinary manner. He grabbed a handful of incense powder and threw it to the altar.

Accounts

Ota Gyuichi (1527-1613), a samurai who served Nobunaga, writes[1]:

Nobuhide, suffering from an epidemic, got various prayers and treatments, but he did not heal and finally on 3 March, passed away as young as 42 years old. Life is ephemeral, as usual; it is sad. It is just like a wind blows off dews on thousands of grass leaves, or like an endless cloud spreads out to hide the light of the full moon.

While alive he built a temple and named it Banshoji. Named Togen as a posthumous name, he was celebrated by holding an alms-giving ceremony, inviting priests from all over the province; it became a big funeral ceremony.

At that time trainee monks travelled up and down the road to Kanto region. There were about 300 monks, Nobunaga's companions are the chief retainers - Hayashi, Hirate, Aoyama, and Naito. His younger brother, Kanjuro, was accompanied by his vassals, Shibata Gonroku, Sakuma Daigaku, Sakuma Jiuemon, Hasegawa, Yamada and so on.

Nobunaga showed up to burn incense. Nobunaga, then, armed with a long-handled sword and a wakizashi wrapped with straw ropes, with his hair tied into a chasen-shaped topknot, without wearing hakama trousers, went to the altar of Buddha, grabbed a handful of incense powder, hurled it to the altar, and went home. His yonger brother, Kanjuro, wearing a sharply creased kataginu vest and hakama trousers, followed the custom in the correct manner. The people variously said that Nobunaga was a great fool as had been rumoured. Among them, a travelling monk from Tsukushi Province, reportedly, said that that was the man who shall be the Landlord.

Venue and Date

The funeral ceremony was held at the Banshoji Temple in Nagoya. The Banshoji Temple, today in the 21st century, is on the Banshoji Street crowded with people shopping and dining, but before it was moved to the present place in 1610 when the Nagoya Castle was built, the temple was located in the blocks south of the present Nagoya Castle.

Not only location but also buildings were changed since Nobunaga's time: the present building, a five-story, concrete building which has an animated figure of Nobunaga throwing incense, was built in 1994, after the temple was burned down in WW2. Before the burning the temple had seven main wooden buildings placed in the conventional Zen buddhist temple layout[2].

The funeral, which 300 monks and many samurais attended, was probably held in the largest building called Taiden (Large Hall). The Taiden in the Banshoji Temple, according to the geography book printed in 1844[3], was an one-story building with a hip-and-gable roof. The floor plan can be estimated by the wooden pillars: eight pillars in the front wall indicate that the width of the front wall was 14 meters, seven pillars in the side wall measure 12 meters. That created large space in the hall to house an imposing Buddhist altar and a space in front of it for hundreds of worshippers.

As for date, Ota Gyuichi's document reads that Nobuhide died on March 3, The year is not written, but another source, a collection of samurai signatures on documents extant, contains Nobuhide's signature with the date of April 24, Tenbun 20(1551), so he likely was still alive in 1551 and died in 1552[4]. Funeral would be held every seven days until the 49th day after death. The date of the Nobuhide's funerel is unknown but if it was the 49th day funeral, the most important ceremony, the date was April 21 on the old Japanese calendar (14 May on the Julian calendar) [2]

Characters

Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582), was Nobuhide's third son. Though he was the legitimate successor of Nobuhide, he was not accepted by the vassals as a landlord. He was called a fool because of his behaviour: when walking through the town, Nobunaga was biting into a chestnut, a persimmon, and a melon[1], that was considered rude in Japan. He walked leaning against a man on his shoulder[1], that was considered rude in Japan.

Hayashi Hidesada (1513-1580), was Nobunaga's first chief retainer. He assisted Nobunaga who was given Nagoya Castle by his father. But Hayashi was not royal to Nobunaga after Nobuhide's death. Three years later, in 1555, he was to support Nobunaga's brother, Kanjuro, to revolt against Nobunaga,

Hirate Masahide (1492-1553), was Nobunaga's second chief retainer. He had been a tutor since Nobunaga's birth. As a chief retainer, he supported Nobunaga joining the battle for the first time, and arranged Nobunaga's marriage to the daughter of the hostile warlord, Saito Dosan, for a matrimonial alliance[1]. But he could not correct Nobunaga's bad behaviour. The following year, in 1553, Nobunaga had a grudge against Hirate, since Hirate's eldest son once had refused Nobunaga's request for a great horse he owned, Hirate committed a suicide[1].

Daiun Eizui (1482-1562), was Nobunaga's grandfather's brother. He had been the chief priest of the Bansyoji Temple since its foundation in 1540.

Oda Kanjuro Nobukatsu (1536?-1558), was Nobunaga's younger brother from the same mother. Kanjuro, at his father's castle, was going to succeed the government of the province when his father was sick. After the father's death, Kanjuro was to fight with Nobunaga for the initiative of the government, but he was defeated by Nobunaga in the battle in 1556. and lost the support of his vassals. In 1558, he was killed by Nobunaga who pretended to be sick to lure the brother to his castle to kill him[1].

Sakuma Daigaku Morishige (?-1560?), was Kanjuro's vassal. As the rivalry intensified between the Oda brothers, however, Sakuma sided with Nobunaga, and contributed to Nobunaga's victory in the battle in 1556.

Sakuma Jiuemon Nobumori (1528?-1582), was Kanjuro's vassal. As the rivalry intensified between the Oda brothers, however, he, together with Sakuma Daigaku, sided with Nobunaga.

Shibata Gonroku Katsuie (1522?-1583), was Kanjuro's vassal. He conspired with Hayashi Hidesada to promote Kanjuro and made a battle with Nobunaga in 1556[1]. After defeated in the battle, Shibata surrendered to Nobunaga and thereafter served him.

Funeral

In a Buddhist funeral, an attendant burn incense in front of an altar of Buddha in a certain way, that is called shoko (burning incense). The basic way of shoko is to pick up a pinch of incense powder in a incense caddy with the right hand and put it in a bowl of smouldering incense, though it differs a bit in Buddhist sects: in the Soto-Zen-sect, an attendant burns incense twice, and at the first time he raises it to in front of his face; in the Shingon-sect, an attendant burns incense once or three times.

So is there any sect which regulates the way of shoko in which an attendant grabs a handful of incense powder and hurls it in a manner Nobunaga did?

There are eight major sects of Buddhism in Japan today in the 21st century, but their way of shoko differs only in two things: times of burning incense — from once to third times, and whether the incense is raised to the face or not.

So what was the manner of shoko in Nobunaga's time and in the due sect?

The Banshoji Temple is a Zen Buddhist temple. Manners in Zen Buddhism was passed down since stipulated by the Zen master, Baizhang Huaihai(749-814 AD). The oldest remaining book, Zennen Shingi [5], written in 1103, regulates the way of shoko:

The method of burning incense: at the east of the incense table, the abbot salutes. Then start the shoko: Raise the incense caddy with both hands. Use the right hand to put the caddy in the left hand. Use the right hand to lift the lid of the incense caddy and put it on the incense table. Use the right hand to raise the incense and burn it for someone to pay tribute. Use the right hand to return the lid to the incense caddy. Raise the incense caddy with both hands and put it on the incense table.

Comparing with the present way of shoko, though there is a bit of difference: the attendant raises the incense caddy with both hands, the way written in the Zennen Shingi has common in its basic form: using right hand to raise the incense before burning it. So, it is likely that the fundamental way of shoko remains almost unchanged for a thousand of years.

Nobunaga's shoko, therefore, was an extraordinary event in the thousand years of shoko history.

Interpretation

Nobunaga's foolish shoko might be one of the reasons why some of his vassals left Nobunaga to serve his brother: those who witnessed Nobunaga's shoko said that he was so fool that he was not the right person to succeed his father, but a monk from Tsukushi Province said that he was the man who should be a landlord. Though he might say an irony, he was to be right: Nobunaga was to rule not only Owari Province, but also more than thirty provinces and became the major senior of Japan[6].

So why did Nobunaga do shoko in such an outrageous manner?

He might be upset by his father's death, but that was not the only reason. His contemporary, Luis Frois, a Jesuit missionary, writes about Nobunaga facing his father's death[6]:

When his father was dying in Owari Province, he asked buddhist monks to pray for his father's life and asked if his father would recover from his illness. They assured that he would recover. But a few days later he died. So Nobunaga confined the buddhist monks in a temple, closed the door from the outside, said that the monks had alleged falsehoods about their father's health, so, now they should pray to the idols with more care for your life. Then after he besieged them from outside, he shot some of them dead.

In this context, it is reasonable to consider that Nobunaga's shoko shows his transforming attitude to Buddhism: he was sceptical of religious faith; he was to disrespect worshipping gods and Buddha, did not believe in an afterlife[6].

Buddhist temples in Japan were growing their power throughout the Middle Ages, and in Nobunaga's time they already had established them as traditional authorities. They controlled vast amounts of wealth — they were large landowners, supported by tens of thousands of believers, able to mobilize an army of tens of thousands of soldiers.

Buddhist powers were the biggest obstacles for Nobunaga who was going to establish samurai regime. In the following three decades, Nobunaga fought with buddhist temples that resisted to be under his control or sided with his rival warlords. He burned hundreds of Buddhist temples, killed thousands of Buddhist monks and tens of thousands of believers,

Nobunaga's violent shoko, though it may be an afterthought, presaged decades of bloody war against Buddhism authorities.

Details

References

[1] 信長公記, 太田牛一

[2] 亀山志:名古屋万松寺史(1932)

[3] 尾張名所図会. 前編 巻2 愛智郡(1844)

[4] 信長公記を読む,和田裕弘(2009) p28

[5] 禪苑清規 卷五(1103)

[6] 完訳フロイス日本史, Luis Frois

Nobunaga On Canvas https://nobunagaoncanvas.blogspot.com/2021/08/shoko-14-may1552.html