ジュラシック・パークを破壊へと導いたデニス・ネドリー技師のアイドルはオッペンハイマー(藤永茂・アルバータ大学理学部名誉教授、他)

諸事情により、一つ前の記事

から分離しました。

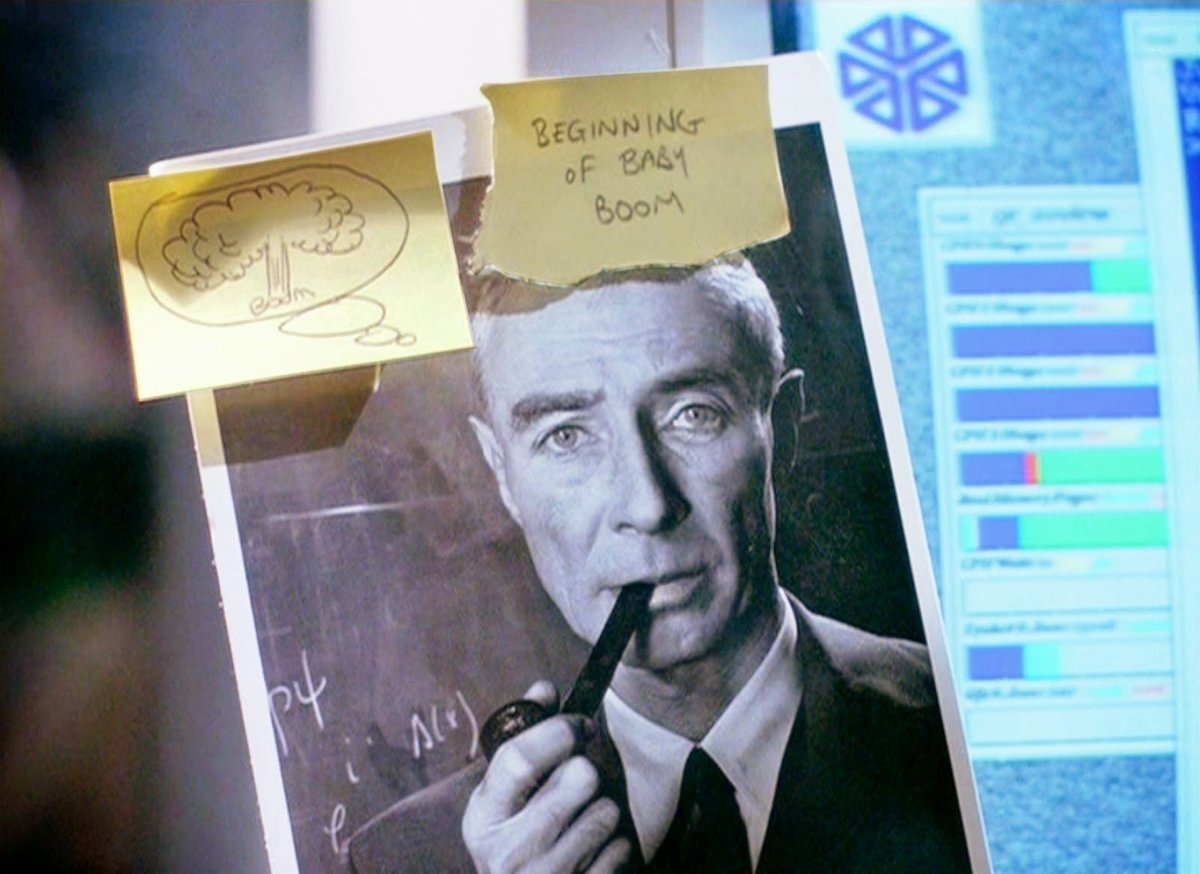

ジュラシック・パーク(1993年)を破壊へと導いた(故)デニス・ネドリー氏(システム・エンジニア)(コンピューター技師)はオッペンハイマーを崇拝していたようです。念のため、備忘録として書き留めます。

『ジュラシック・パーク』という映画がある。これまでに数百万の人が見た映画だろう。その中にロバート・オッペンハイマーの肖像写真が大写しになる所がある。恐竜パークを管理するコンピューターのモニター・スクリーンの向かって左側に貼りつけられている。オッペンハイマーの顔のすぐ上には原爆のキノコ雲のマンガも貼ってある。そのコンピューターを操作する男ネドリーにとっては、オッペンハイマーがアイドルであることを、この映画の監督スピルバーグはきわめて意識的に示そうとしているのである。ここに、オッペンハイマーとは私たちにとって何かという問題が見事にまとまった形で顔を出している。

藤永茂(アルバータ大学理学部名誉教授)著

In Jurassic Park, Dennis Nedry has a photo (taped to his computer monitor) of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb" who famously said, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

はじめに――〝InGen事件〟

二十世紀も残り四半世紀というあたりから、科学畑のゴールドラッシュともいうべき現象がはじまった。すさまじいまでの速さで性急に進められていく、遺伝子工学の事業化である。この事業の発展ぶりたるや、まさに猛烈のひとことにつきるが、外部にはめったに情報が漏れてこないこともあって、その特徴や意義は一般にほとんど理解されていない。

バイオテクノロジーは、人類史上最大の革命を約束する。二十世紀がおわるまでには、原子力やコンピュータよりもはるかに大きな影響を日常生活にもたらしているだろう。ある事情通のことばを借りるなら、こういうことだ。

「バイオテクノロジーは、人間生活のあらゆる局面を変化させようとしている。医療、食料、健康、娯楽、さらには人の肉体そのもの。革新ののち、ものごとは二度ともとにもどらない。それは文字どおり、この惑星の様相をも一変させてしまうだろう」

だが、このバイオテクノロジー革命には、これまでの科学革命と比べ、三つの大きなちがいがある。

第一に、大々的に研究がなされていること。アメリカに原子力時代をもたらしたのは、ロスアラモスの一研究機関だった。コンピュータ時代をもたらしたのも、せいぜい十社強の企業でしかない。ところが、バイオテクノロジー研究となると、アメリカ一国を例にとっても、研究機関は二〇〇〇を超える。企業だけ見ても約五〇〇社で、その五〇〇社が投じている資金は、じつに年間五〇億ドルにものぼる。

第二は、研究の大半が無思慮で軽薄なこと。たとえば、川を泳ぐ姿が見つけやすいように体表の色を明るくしたマス、製材しやすいように最初から四角く育つ木、いつも好きなにおいを嗅いでいられるよう鼻に注入する香り細胞――。冗談のような話ばかりだが、これは冗談ではない。じっさい、化粧品会社やレジャー産業など、伝統的に流行に敏感な業界がこの新しいテクノロジーがとりいれれば、その気まぐれな使い方の実態がひときわ関心を引くようになるだろう。

第三に、この研究は管理不可能なこと。監督当局がない。規制する連邦法もない。アメリカはもちろん、世界じゅうのどの国を見まわしても、終始一貫した当局の方針などない。そもそもバイオテクノロジーの産物は、医薬品から穀物生産、人工降雪にいたるまで多岐にわたっているため、統一のとれた政策を貫くのがむずかしいのだ。

しかし、なによりもやっかいなのは、科学者たちのなかにお目つけ役をもって任じる人物がひとりもいないことである。驚くべき話だが、遺伝子研究に携わる科学者は、ほぼ全員がバイオテクノロジーの商業利用にかかわっている。超然たるオブザーバーなどいるわけがない。だれもかれもがヒモつきなのだから。

分子生物学の実用化は、科学史においてとびぬけて深刻な倫理問題といえる。しかもその研究は、目を見張るばかりの勢いで進められてきた。ガリレオ以来四〇〇年間、科学はつねに、自然の働きに対する自由でオープンな研究だった。科学者はつねに国境を越え、政治や戦争の移り気な関心を超越した場所にみずからを位置づけてきた。研究を秘密にされることには決まって抵抗し、自分の発見で特許をとるという考えにすら眉をひそめ、科学研究は全人類の利益のためだという姿勢を貫いてきた。事実、何世代にもわたって、科学者の諸発見は、たしかに利己的な性質とは無縁のものだったのである。

一九五三年のこと、ジェイムズ・ワトソンとフランシス・クリックという英国の若い研究者が、DNAの構造を解明した。ふたりの研究は、人間の魂の――宇宙を科学的に理解しようとする何世紀もの探求の――一大勝利として、熱烈な歓迎を受けた。そして、人類のいっそう大きな利益のために、無私の形で活用されるものと考えられた。

ところが――。三〇年たってみれば、ワトソンとクリックの研究仲間たちは、ほぼ全員が、それとはまったく異なる分野に従事していた。すなわち、分子遺伝学である。何十億ドルもの巨利を生むまでに成長したこの研究の源をたどれば、一九五三年ではなく、一九七六年四月にたどりつく。

この年、いまでは有名となった出会いがあった。ベンチャー企業家のロバート・スワンソンが、カリフォルニア大学の生化学者、ハーバート・ボイヤーに接近したのである。ふたりは合意に達し、ボイヤーの組み換えDNA技術を応用するために、営利企業が設立される運びとなった。その名をジェネンテク社という。この新会社はまたたく間に成長し、最大かつもっとも業績の高い遺伝子工学企業にのしあがった。

以来、だれもかれもが急に金持ちになりたがりだしたように見える。毎週のように新会社の設立が報じられ、科学者たちは遺伝子研究に群がった。一九八六年の時点では、科学アカデミーに所属する六四名をふくめ、バイテク企業の顧問会議に名を連ねていた科学者はすくなくとも三六二名を数えた。株を所有していた者、コンサルタントを務めていた者の数となると、さらにこの数倍にもふくれあがる。

科学者たちのこのような態度の変化がどれほど重要であるかは、ここで強調しておく必要がありそうだ。そのむかし、純粋な科学者は、ビジネスを見くだす傾向があった。金もうけなど知的な興味をかきたてるものではなく、商売人にまかせておけばよいと考えていた。産業のための研究など、たとえベル研究所やIBMのような有名どころの仕事であっても、しょせんは大学で研究を認められない者のすることだと見なしていた。したがって、学究肌の科学者というものは、企業の御用科学者の研究はもとより、産業全般に対し、基本的に批判的であったといえる。そして、この伝統的な反感があったからこそ、技術的問題にかかわる問題が持ちあがったとき、営利にとらわれない大学の科学者は、高次の次元で問題を議論することができたのである。

だが、もはやそんな美風はない。ヒモつきでない分子生物学者、ヒモつきでない研究機関など皆無に等しい。時代は変わった。遺伝子の研究は、以前にも増して猛烈な勢いで進められている。それも、秘密裏に、性急に、ひたすら利益のために。

インターナショナル・ジェネティック・テクノロジー社(通称InGen社、本社パロアルト)のような野心的な企業が出現したのは、このような土壌があったればこそのことである。そして、あのような遺伝子危機が闇から闇へ葬りさられたことも、やはり驚くにはあたらない。そもそも、InGen社の研究は秘密裏に行なわれていたうえ、事件が起こったのは中米でも僻地中の僻地でのことだったのだ。事件の当事者は二十数名。生き残った者はその半数弱にすぎない。 事件のかたがつき、一九八九年十月五日、サンフランシスコ上位裁判所でInGen社が連邦破産法第一編第十一章の適用を受け、会社更生手続きをとられたときも、この審理はまったくマスコミの注目を集めることがなかった。ごくあたりまえの裁判に見えたからだろう。アメリカの中小遺伝子工学企業のうち、同年に倒産したのはInGen社が三件め、一九八六年から通算しても七件めだった。審理の記録はいっさい公表されずじまい。債権者がジャパン・マネー、それもハマグチやタサカという、伝統的に人目につくのをきらう企業だったためである。無用の暴露を避けるにあたっては、InGen社の弁護士でもあったカウアン、スウェイン&ロス法律事務所のダニエル・ロスが、ジャパン・マネーの依頼を受けて暗躍したとささやかれる。さらに、コスタリカの副領事からも異例の請願がとどいたとのうわさも漏れ聞こえてくる。となれば、事件からひと月たらずでInGenがらみのごたごたが終息し、八方まるく収まったことは、意外事でもなんでもないというべきだろう。 著名な科学者顧問団をふくむ関係者たちは、秘密厳守を申し合わせる承諾書にサインし、事件については固く口を閉ざして語ろうとしない。だが、かの〝InGen事件〟にかかわった主要な当事者の多くはそれにサインしておらず、進んで語ってくれた。一九八九年八月の最後の二日間、コスタリカ西海岸の離島で起きた、あの驚くべき事件のことを――。

マイクル・クライトン著 ジュラシック・パーク 早川書房

INTRODUCTION

“The InGen Incident”

The late twentieth century has witnessed a scientific gold rush of astonishing proportions: the headlong and furious haste to commercialize genetic engineering. This enterprise has proceeded so rapidly - with so little outside commentary - that its dimensions and implications are hardly understood at all.

Biotechnology promises the greatest revolution in human history. By the end of this decade, it will have outdistanced atomic power and computers in its effect on our everyday lives. In the words of one observer, “Biotechnology is going to transform every aspect of human life: our medical care, our food, our health, our entertainment, our very bodies. Nothing will ever be the same again. It’s literally going to change the face of the planet.”

But the biotechnology revolution differs in three important respects from past scientific transformations.

First, it is broad-based. America entered the atomic age through the work of a single research institution at Los Alamos. It entered the computer age through the efforts of about a dozen companies. But biotechnology research is now carried out in more than two thousand laboratories in America alone. Five hundred corporations spend five billion dollars a year on this technology.

Second, much of the research is thoughtless or frivolous. Efforts to engineer paler trout for better visibility in the stream, square trees for easier lumbering, and injectable scent cells so you’ll always smell of your favorite perfume may seem like a joke, but they are not. Indeed, the fact that biotechnology can be applied to the industries traditionally subject to the vagaries of fashion, such as cosmetics and leisure activities, heightens concern about the whimsical use of this powerful new technology.

Third, the work is uncontrolled. No one supervises it. No federal laws regulate it. There is no coherent government policy, in America or anywhere else in the world. And because the products of biotechnology range from drugs to farm crops to artificial snow, an intelligent policy is difficult.

But most disturbing is the fact that no watchdogs are found among scientists themselves. It is remarkable that nearly every scientist in genetics research is also engaged in the commerce of biotechnology. There are no detached observers. Everybody has a stake.

The commercialization of molecular biology is the most stunning ethical event in the history of science, and it has happened with astonishing speed. For four hundred years since Galileo, science has always proceeded as a free and open inquiry into the workings of nature. Scientists have always ignored national boundaries, holding themselves above the transitory concerns of politics and even wars. Scientists have always rebelled against secrecy in research, and have even frowned on the idea of patenting their discoveries, seeing themselves as working to the benefit of all mankind. And for many generations, the discoveries of scientists did indeed have a peculiarly selfless quality.

When, in 1953, two young researchers in England, James Watson and Francis Crick, deciphered the structure of DNA, their work was hailed as a triumph of the human spirit, of the centuries-old quest to understand the universe in a scientific way. It was confidently expected that their discovery would be selflessly extended to the greater benefit of mankind.

Yet that did not happen. Thirty years later, nearly all of Watson and Crick’s scientific colleagues were engaged in another sort of enterprise entirely. Research in molecular genetics had become a vast, multibillion-dollar commercial undertaking, and its origins can be traced not to 1953 but to April 1976.

That was the date of a now famous meeting, in which Robert Swanson, a venture capitalist, approached Herbert Boyer, a biochemist at the University of California. The two men agreed to found a commercial company to exploit Boyer’s gene-splicing techniques. Their new company, Genentech, quickly became the largest and most successful of the genetic engineering start-ups.

Suddenly it seemed as if everyone wanted to become rich. New companies were announced almost weekly, and scientists flocked to exploit genetic research. By 1986, at least 362 scientists, including 64 in the National Academy, sat on the advisory boards of biotech firms. The number of those who held equity positions or consultancies was several times greater.

It is necessary to emphasize how significant this shift in attitude actually was. In the past, pure scientists took a snobbish view of business. They saw the pursuit of money as intellectually uninteresting, suited only to shopkeepers. And to do research for industry, even at the prestigious Bell or IBM labs, was only for those who couldn’t get a university appointment. Thus the attitude of pure scientists was fundamentally critical toward the work of applied scientists, and to industry in general. Their long-standing antagonism kept university scientists free of contaminating industry ties, and whenever debate arose about technological matters, disinterested scientists were available to discuss the issues at the highest levels.

But that is no longer true. There are very few molecular biologists and very few research institutions without commercial affiliations. The old days are gone. Genetic research continues, at a more furious pace than ever. But it is done in secret, and in haste, and for profit.

In this commercial climate, it is probably inevitable that a company as ambitious as International Genetic Technologies, Inc., of Palo Alto, would arise. It is equally unsurprising that the genetic crisis it created should go unreported. After all, InGen’s research was conducted in secret; the actual incident occurred in the most remote region of Central America; and fewer than twenty people were there to witness it. Of those, only a handful survived.

Even at the end, when International Genetic Technologies filed for Chapter 11 protection in United States Bankruptcy Court in San Francisco on October 5, 1989, the proceedings drew little press attention. It appeared so ordinary: InGen was the third small American bioengineering company to fail that year, and the seventh since 1986. Few court documents were made public, since the creditors were Japanese investment consortia, such as Hamaguri and Densaka, companies which traditionally shun publicity. To avoid unnecessary disclosure, Daniel Ross, of Cowan, Swain and Ross, counsel for InGen, also represented the Japanese investors. And the rather unusual petition of the vice consul of Costa Rica was heard behind closed doors. Thus it is not surprising that, within a month, the problems of InGen were quietly and amicably settled.

Parties to that settlement, including the distinguished scientific board of advisers, signed a nondisclosure agreement, and none will speak about what happened; but many of the principal figures in the “InGen incident” are not signatories, and were willing to discuss the remarkable events leading up to those final two days in August 1989 on a remote island off the west coast of Costa Rica.

Jurassic Park: A Novel by Michael Crichton (Random House Publishing Group)