Japanese Law Update #14: The Japanese Government Mandates a 30% Female Board Member Ratio for Japanese Listed Companies by 2030

In June 2023, the Japanese government announced its policies which will be the basis for formulating the budget for the next fiscal year in Japan, called the 2023 Version of Framework Policies (honebuto no hoshin, “2023 Policies”). This article analyzes the government's policies included in the 2023 Policies aiming to improve the ratio of female board members and the challenges posed by the “L-shaped curve” of female regular employment in Japan, which could hinder the achievement of the set goals.

Japan ranked 125th out of 146 countries in terms of gender parity in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2023. Japan is at the bottom of the list in East Asia and the Pacific. The report says that “it will take 189 years for the region to reach gender parity”.

1. The government demands a 30% female board member ratio for Prime market listed Japanese companies by 2030

On June 16, 2023, the Japanese government finalized the details of the 2023 Policies. The policies set a numerical target for the Prime market listed companies, requiring them to achieve a female board member ratio of 30% or more by 2030. According to reports, the Tokyo Stock Exchange listing rules are expected to include the new goals by the end of 2023.

In recent years, the appointment of female board members, particularly as outside non-executive directors, has rapidly increased in Japan, driven by various factors such as:

The 2021 amendment to the Companies Act, which mandates the appointment of an outside director for certain types of listed companies.

The 2021 edition of the Corporate Governance Code by the Tokyo Stock Exchange, which seeks to improve diversity in boards of directors (Principle 4-11).

Voting guidelines, such as the Glass Lewis 2023 Policy Guidelines Japan and the ISS 2023 Japan Proxy Voting Guidelines, which recommend opposition to the appointment of top management directors when their boards lack female directors.

The activities of the 30% Club Japan, which have aimed at achieving gender balance in decision-making bodies.

As a result, the number of Japanese listed companies without any female board member has decreased. According to the Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office's report on gender diversity, the percentage of companies without female board members in the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime market listed companies was 18.7% as of 2022, down from 84.0% in 2013. The trend of appointing female board members in listed companies is accelerating even further in this year's June shareholder meetings, which marks the peak season of shareholder meetings in Japan. Therefore, the percentage of Japanese listed companies without any female board members is expected to decrease further this year. The 2023 Policies go a step further and set specific numerical targets: one or more female board members by 2025 and a female board member ratio of 30% or more by 2030. 30% is particularly important, because, as critical mass theory tells, 30% is the minimum percentage at which minority would have an influence in a decision-making body. The new goals initially seek to promote gender diversity in boards of directors. However, according to reports, companies which violate these rules may not face penalties.

2. Challenges in the formation of a pipeline of female board candidates - the “L-shaped curve” of regular employment ratio

In the 2023 Policies, the improvement of the female board member ratio is positioned as one of the efforts to resolve the “L-shaped curve,” which will be described below. However, a critical weakness of this approach is that the “L-shaped curve” itself is a significant factor hindering the formation of a pipeline for female board candidates in Japanese companies, and it is not a straightforward task to solve these two interreferential issues.

Generally, in Japan, the labor market has low fluidity, and the appointment of professional executives as new board members is relatively uncommon in Japanese companies. As a result, individuals who have been employed as regular employees (“seiki koyo”) for many years often become board members through internal promotions.

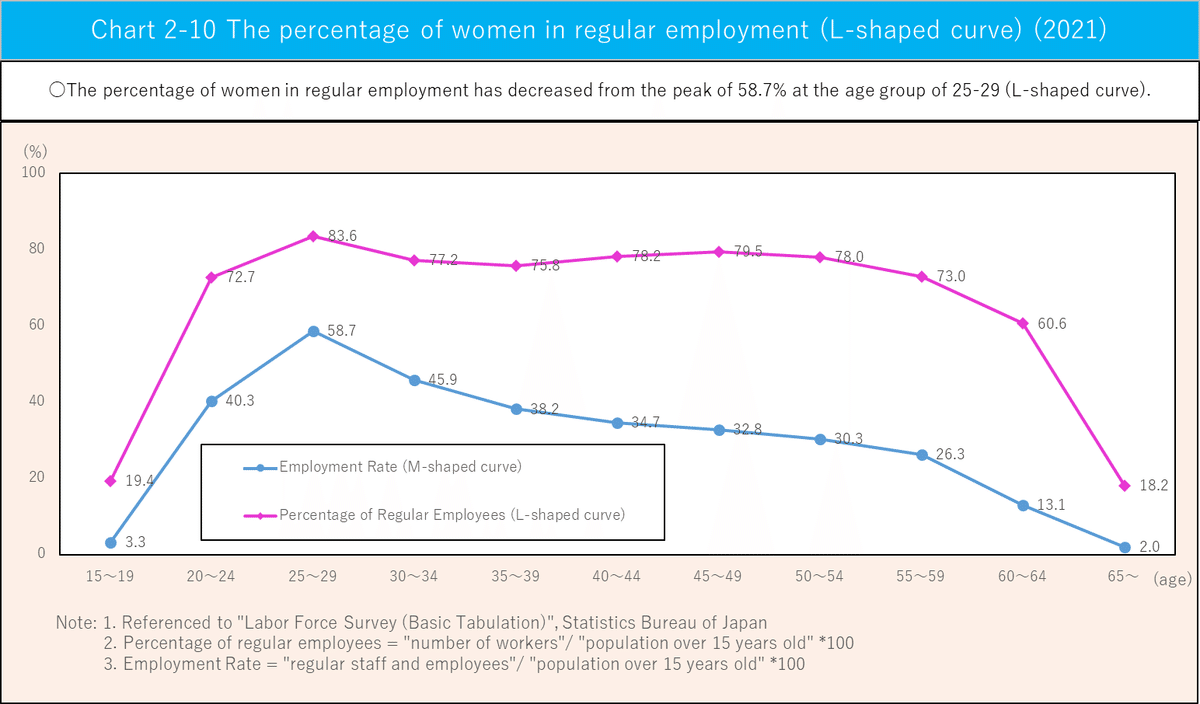

On the other hand, opportunities for female employees to become board candidates through internal promotions have been extremely limited due to phenomena known as the “M-shaped curve” and the “L-shaped curve,” which are described below.

The “M-shaped curve” refers to the trend where women retire from their jobs to take on family responsibilities such as housekeeping and childcare, and then re-enter the workforce after their child-rearing period. This leads to an M-shaped employment rate pattern for women. It is worth noting that the “M-shaped curve” has been gradually diminishing in recent years in Japan.

The “L-shaped curve” refers to the rapid decline in the regular employment ratio of women in Japan, peaking at around the age of 30. In Japanese companies, there are regular employees (“seiki koyo”) who are protected by various labor laws and are subject to restrictions on dismissals, as well as non-regular employees (“hi seiki koyo”) who have limited employment safeguards. According to the graph of the “L-shaped curve” in the Gender Equality White Paper (2022) by the Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, the regular employment ratio of women sharply declines after reaching its peak in the late 20s, dropping to a level where they are considered potential board candidates in many companies. As shown in the Chart 1. below, the ratio goes down to 30.3% in their early 50s, 26.3% in their late 50s, and 13.1% in their early 60s, as of 2021.

As a result, the currently most realistic and common strategy employed by Japanese companies to increase the ratio of female board members is to appoint external professionals such as lawyers, accountants, and university professors as non-executive outside directors. This strategy is sometimes explained as a temporary measure until women in executive positions can be cultivated internally. However, if Japanese companies cannot mitigate the aforementioned “L-shaped curve” rapidly, the pipeline for female executive board candidates will remain unstable and significantly limited.

3. Legislative measures to mitigate the “L-shaped curve”

To mitigate the “L-shaped curve” and change the prevailing situation where women bear the majority of family responsibilities, it is worth examining recent developments in labor laws that aim to establish an environment where both men and women continue working as well as caring for their family. For example, the following new rules have been introduced to promote such an environment:

Disclosure of gender wage gap based on the Act on the Promotion of Women’s Active Engagement in Professional Life.

Under this new rule, which was fully implemented in 2023, companies with a workforce of 301 or more employees are obliged to disclose their gender wage gap. (For more details, please refer to Japanese Law Update #12.) As of 2020, Japan’s wage levels for women significantly lagged behind the OECD average of 88.4%, with women earning only 77.5% of what men earned.

According to a recent disclosure made based on the new rules, there are companies where women’s wages are less than 50% of men’s wages. On the other hand, some companies have used the new rules to analyze the causes of the existing wage gap and outline the steps they will take to mitigate it, including reforming their human resource systems. The disclosed information of companies can also be found on the website (in Japanese) of the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare’s Database of Companies Promoting Women’s Active Participation.

Amendments to the Act on Childcare Leave, Caregiver Leave, and Other Measures for the Welfare of Workers Caring for Children or Other Family Members, effective in 2023

To promote the uptake of childcare leave and other related leave by male employees, the amendments oblige companies to disclose the rate of male employees taking childcare leave and other related leave. In recent years, there have been efforts in Japan to design systems that encourage men to share family responsibilities. This new rule indirectly incentivizes companies to ensure the uptake of childcare leave by male employees by making companies disclose information.

Increase in overtime pay rates through the amendments of the Labor Standards Act

One of the causes of the “L-shaped curve” for women is the prevalent practice of long working hours in Japan. In past years, long working hours were sometimes used to measure employees’ contribution to the company. As part of recent legislative measures to address excessive overtime work, there has been an amendment to raise the overtime pay rate from 25% to 50% for monthly overtime work exceeding 60 hours. This serves as an incentive for companies to reduce long working hours among their employees.

These legislative measures aim to create an environment that facilitates greater gender equality and work-life balance, addressing the challenges associated with the “L-shaped curve.”

4. Gender balance in the board room of Japan

Currently, if Japanese companies want to have a female director, they tend to search for candidates from among outside experts. While there has been significant progress compared to having no women on boards of directors, the appointment of women as executive directors who perform operational duties remains limited. In 7 years, Prime market listed companies are expected to have more than 30% of their directors be women. It is desirable to include women not only as external non-executive directors but also as executive directors responsible for business operations. The elimination of hindering factors such as the “L-shaped curve” is not only an urgent challenge for companies to secure their workforce in a “super-aged” society, but also crucial from the perspective of corporate governance and as a strategy for survival and growth in the market.

Author

Yoshie Midorikawa, Partner

Yoshie Midorikawa has extensive experience in complex disputes and arbitration. Having worked with leading law firms in Japan and Singapore, she has handled parallel proceedings across multiple jurisdictions as well as domestic disputes before Japanese courts. She has also served as a board member of listed companies in Japan, improving their corporate governance. Her deep understanding of the civil law system, her working experience in international environments, including common law jurisdictions, and her knowledge of business, enable her to bring practical and nuanced legal solutions to international businesses. She is listed among “Next Generation Partners (Dispute Resolution)” by Legal500 Asia Pacific 2023, “Best Lawyers in Japan (Litigation)” in the editions of 2021 to 2024, “Best Lawyers in Japan (Corporate Governance & Compliance)” in the edition of 2023 and 2024, “Best Lawyers in Japan (International Arbitration)” in the edition of 2024 by Best Lawyers.