Book notes - "Designing Japan", by Kenya Hara

I recently purchased a whole slew of books as part of my yearly book budget at Takram (employees get a generous yearly budget for book purchases, which was expiring soon).

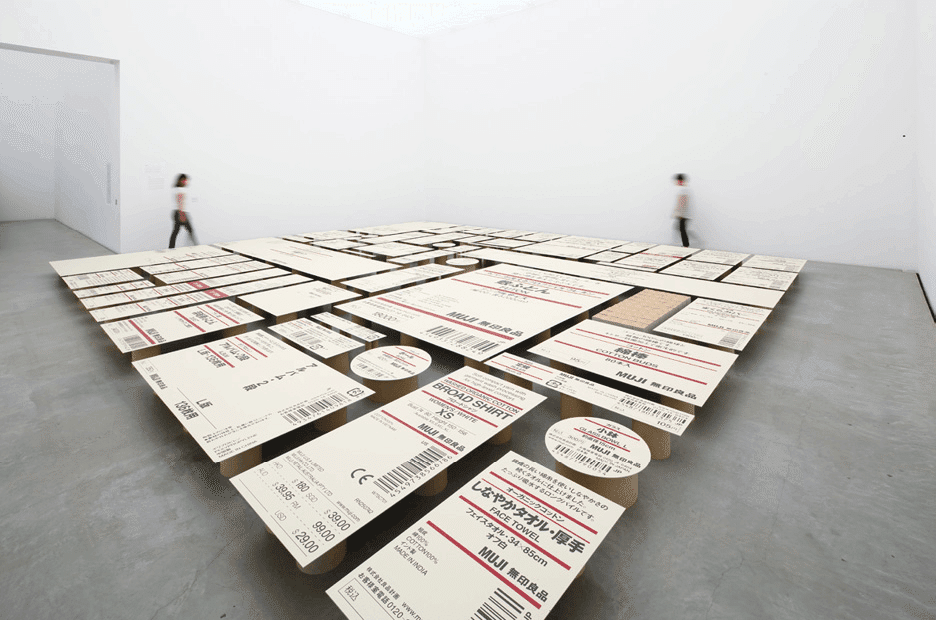

In order to get more familiar with some famous Japanese designers that I hadn't taken the time to dive into yet, I purchased a couple of books by Kenya Hara (designer of MUJI's brand identity, and arguably the most famous contemporary Japanese designer).

This article is to record my thoughts on one of those books, "Designing Japan" (English version, 2018; translated from the original Japanese version, 2011).

1: The book itself

The book's main tenet is this:

It is about how, in the face of globalization, countries or localities can maintain their culture and generate value from it. It is about finding how to mine their culture’s "soft" values to be used as economic resources in the future. The book focuses on the case of Japan, but the idea could apply to anywhere else. Especially for places where, as all over Asia, Westernization made the local culture undervalued until now — therefor, there is still much value to be extracted from local cultures that is yet undiscovered by the rest of the world.

The point is developed by examples in each chapter:

Introduction: Aesthetics as a Resource

Hara argues that Japan's main economic resource for the future is its aesthetic sensibility rather than natural resources. In a world of changing economies of power and declining natural resources, this "resource of sensibility" is a unique cultural byproduct built over millennia which cannot be bought.

Chapter 1 - Movement: A Design Platform

Hara established Design Platform Japan, a nonprofit organization for launching design exhibitions introducing Japan's design culture to overseas audiences. A culture's power to influence the world will overtake the power of money in the future. "JAPAN CAR: Designs for the Crowded Globe" (2008) was the first exhibition doing so, displaying the modern rise of Japanese car making and its focus on practicality. Hara envisions a future for the industry in which vehicles could turn into habitat or urban infrastructure.

Chapter 2 - Simplicity and Emptiness: The Genealogy of an Aesthetic

Describes the history of Japan's design culture and how its unique aesthetic of simplicity came about. Mentions the Mingei (folk art) movement; the origin of Japan's aesthetic of emptiness/nothingness starting with the Onin War (1467-77); the difference between Europe and Japan's view on simplicity and it's relation to power; and the effect of the "Ami-shu" starting in the Muromachi period as Japan's original designers and art directors.

Chapter 3 - Houses: Refining the Home

Describes how Japan could deliver the future of housing based on its traditional aesthetics of delicacy, thoroughness, precision, and simplicity. Presents ideas on adapting one's "shape of living" (ie. their homes) based on individual lifestyle rather than market-driven templates; reusing/renovating old homes; a critique of modern Japanese materialism in favor of traditional minimalistic living; Japan's primed position for reinventing the home as an integrated "appliance" that is a hybrid of Japanese tradition and high tech; and the potential for the Japanese home to lead Asian lifestyle culture in the near future.

Chapter 4 - Tourism: Cultural DNA

"No country in the world compares to Japan when it comes to service", begins the chapter. Mentions Junichiro Tanizaki's "In Praise of Shadows" (1931) and negative changes in the Japanese lifestyle by Westernization following the Meiji Restoration; the Aman Resorts as an example for tourism that harvests local culture and deepens customers' curiosity about it; how "experience design" can deliver the future of hospitality; the difference between Asian and European tourists' idea of vacation and Japan's potential for offering a new style more suited to an Asian audience (by embracing the "workcation"); and solidifying Japan as a country of hospitality by creating national parks as information architecture (following the example of Massimo Vignelli's work for the United States' national parks) while pushing the information design angle of the tourism industry.

Chapter 5 - Future Materials: Designing Experience

Hara calls materials that evoke our creatives urges "senseware" and created various exhibitions to attract consumer attention to innovative synthetic fibers made in Japan. "My work serves to imprint values and impressions in people's minds via events, exhibitions, and brand building", says Hara (p.144). He aimed to avoid the conventional, Paris- and Milan-dominated categories of fashion, interiors, and products, instead exhibiting under the themes of people, textiles, and the environment. "[These exhibitions] helped me sense what the world expects from Japan; that was the moment when, through advanced fibers, I arrived at a sense of possibilities for Japan's future" (p.160).

Chapter 6 - Point of Growth: Design for a Future Society

Reflects on the Tohoku earthquake of 2011 and how it might inspire new community-driven solutions to urban reconstruction, revitalization and innovation for the rest of the world. Mentions future global issues like aging populations and declining birth rates which already affect Japan and require "cool collective intelligence" to find solutions. Speaks of his solo exhibition in Beijing and his message for Asia to use design not as a tool for consumption but as a means to "awaken to the essence of everyday living and cultural pride."

"Today, confronted by an era of slow growth, Japan is finally beginning to recognize its own history and traditions as a rare 'soft' resource for creating value in a global context."

"I introduce [examples of art direction for MUJI] to illustrate the value that a philosophy of craftsmanship backed by Japan's unique aesthetic can provide to the world: that simplicity can sometimes surpass luxury and splendor."

"Design plays a significant role in using exhibitions to make visible what is dormant or latent."

2: Reactions

On tourism

Of course, tourism will be a key to Japan's economic future, as it already is one of its strongest economic drivers. "Sustainable" tourism will be especially important, in terms of protecting the environments and habitats that will host these droves of people. Focusing on the uniqueness of local culture for revitalization of areas outside the big cities is also crucial so the tourist influx isn't only concentrated on the big cities, which would lead to other problems.

Coincidentally, I've been reading a book by Alex Kerr, a writer and proponent of revitalizing small Japanese towns, who has similar thoughts on how it should be done: halting the virus of modern Japanese urban planning, and keeping tradition alive by renovating traditional buildings and attracting city dwellers to the countryside. (He has a bunch of great videos on Youtube I recommend looking at.)

One obvious concern, however, is that the COVID-19 pandemic was disastrous for the Japanese tourism industry during the last few years. Conventional tourism is completely vulnerable to pandemic-like scenarios. We need to find solutions to this, where people can feel the benefits of travel in new ways. There's been much hubbub about the metaverse lately, and although it certainly is not a panacea for this problem, perhaps it — and other immersive technologies (AR/VR, etc) — can be used as a temporary solution during events of that nature. Who knows, maybe a whole new type of virtual experience could be discovered, blending tourism with immersive tech, cultural exchange, relaxation, shopping, and more.

On the future home

Hara's idea of the home of the future being akin to an "integrated appliance" that Japan could export all over the world is an incredible, though scary, notion. It reminds me of "The Machine Stops", a science fiction short story by E.M. Forster from 1909 in which humans all live in fully-integrated capsules and only communicate via telepresence devices, à-la-Zoom or Skype. It's especially scary after the pandemic, but I highly recommend reading it.

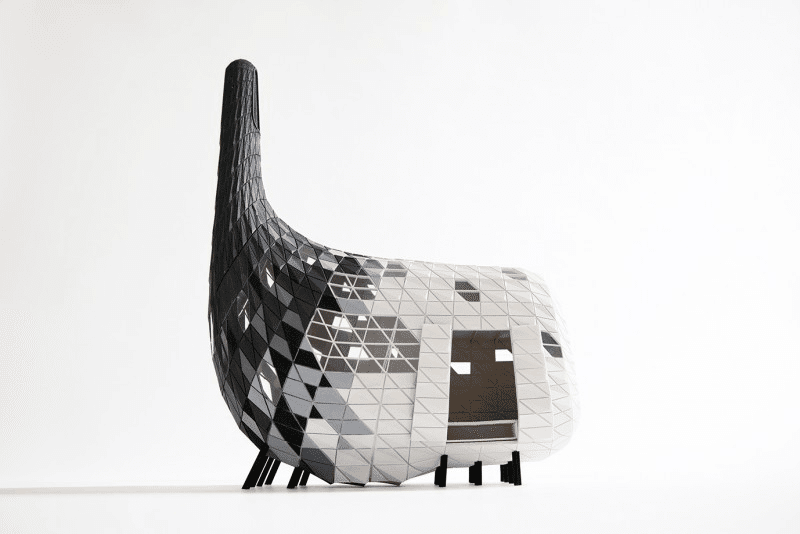

This future home idea also reminds me of the incredibly interesting and thought-provoking work of vHM Design Futures. They've made many brilliant concepts around the future of habitation and future lifestyles. I highly recommend checking-out their work.

Takeaways relating to UI design?

Since I read this book as part of a UI design-related research group, I ponder on how these learnings might relate to it.

Hara has himself made a few projects that extend his ideas and philosophy onto UI design.

In general, the materialization of those ideas seem to simply be an increased focus on the experience design of whatever website or app they are being applied to. A good example is his Setouchi Art Triennale project, in which a map and app were created to solve specific problems that visitors to the many islands of the art festival would run into. Its design process basically seems to echo the activities of the usual UX (experience design) process: persona creation, journey mapping, touchpoint definition, user interviews, and all the other familiar parts of the now typical UX process.

However, I am still thinking about how this book relates to UI design, and hope to report back any realizations I might have later.

3. Next steps

To pursue what the ideas from this book could look like in terms of web & UI design, I have a couple of ideas as to what might be interesting to do next:

Define what exactly the "Japanese aesthetic" is by isolating and collecting the individual elements that form it. Of course, I (as most people) have a sense of what that aesthetic looks like; but what exactly is it that makes something look Japanese? It would be interesting to break that down.

See if these elements can be applied to web & UI design by performing an experiment, eg. designing a website or landing page.

Thanks for reading this far!