Marx and Magnet

Introduction

In “Das Kapital”, Karl Marx says that

³) “Things have an intrinsick vertue (this is by Barbon the specific designation for value in use) , which in all places have the same vertue; as the loadstone to attract iron” (l. c. p. 16). The magnet's property of attracting iron became useful only after by means of that property the magnetic polarity had been discovered.

What is of importance here is “to discover”(zu entdecken)(ibid.). Following Marx's example, the discovery of the magnetic polarity is a “historical act”(geschichtliche That)(ibid.). This “historical act”(geschichtliche That) is the kind of thing that would be given for a great achievement like the first discovery in the history of science. However, it is strange to say that “the magnet's property of attracting iron became useful only after by means of that property the magnetic polarity had been discovered”(die Eigenschaft des Magnets, Eisen anzuziehn, wurde erst nützlich, sobald man vermittelst derselben die magnetische Polarität entdeckt hatte)(ibid.). Isn't a magnet always “useful”(nützlich) just by virtue of the fact that it attracts iron? This means that Marx does not consider the property of the magnet itself (an sich) to be “useful”(nützlich).

In order to understand this point in more detail, in the following, I would like to look at the discovery of magnetic polarity from the perspective of the history of science.

Discovery of magnetic polarity

The Wikipedia entry on “Lodestone” says that

One of the earliest known references to lodestone's magnetic properties was made by 6th century BC Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus, whom the ancient Greeks credited with discovering lodestone's attraction to iron and other lodestones. The name magnet may come from lodestones found in Magnesia, Anatolia.

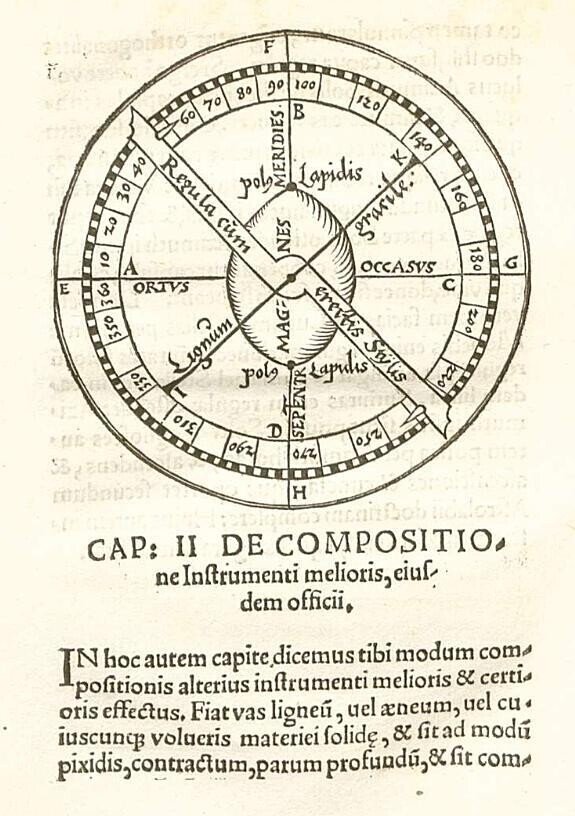

Thus, it can be confirmed that the magnetic property of attracting iron has been recognized since ancient times. However, the discovery of magnetic polarity––what Marx called “historical act”(geschichtliche That)––had to wait until the appearance of Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt's “Letter on the Magnet”(“Epistola de magnete”, 1269). According to Alanna Mitchell,

Peregrinus was the first to figure out that a magnet has two poles. He was one of the few early investigators to note that a magnet repels as well as attracts. But to Peregrinus, the idea of poles did not contain the idea of movement, or of a field. He couldn't have imagined unpaired spinning electrons in an atomic array. His explanation was that the magnet carried within itself a replica of the heavens, by which he meant the stars that point to geographic poles, aligning with the axis of the planet.

However, since Peregrinus thought that the magnetic polarity was in the heavens, it was not yet thought that that was on earth at this time. The idea of geomagnetism is finally confirmed in William Gilbert's “On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth”(“De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure”, 1600). According to Alanna Mitchell,

And while Peregrinus had written three centuries before about a magnet's “natural instinct,” implying that it was a constant property, Gilbert was saying that the whole Earth itself carried this fundamental power, and that the power was inextricably bound to the Earth's core.

Conclusions

According to the above history of science––I don't know if Marx himself was aware of this history of science––there is at least a certain validity in distinguishing the period after Peregrinus' discovery of the magnetic polarity from the earlier period when the magnet's property of attracting iron was recognized.

Therefore, Marx's sentence, “the magnet's property of attracting iron became useful only after by means of that property the magnetic polarity had been discovered”(die Eigenschaft des Magnets, Eisen anzuziehn, wurde erst nützlich, sobald man vermittelst derselben die magnetische Polarität entdeckt hatte), is generally applicable to the history of science.

Bibliography

・Gilbert, William, 1600, De magnete, magneticisque corporibus, et de magno magnete tellure, Londini. (University of Minnesota, 2011).

・Marx, Karl, 1867, Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Oekonomie, Erster Band, Buch 1: Der Produktionsprocess des Kapitals, Hamburg. (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 2014).

・Mitchell, Alanna, 2018, The Spinning Magnet, The Electromagnetic Force That Created the Modern World––and Could Destroy It, New York.

・Peregrinus, 1558, De magnete, seu rota perpetui motus, libellus, Avgsbvrgi in svevis. (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 2014).

この記事が気に入ったらチップで応援してみませんか?