Rydeen, the Galaxy Superhorse (part 2)

[Continued from this] We gave an analysis of his commercial debut, "Thousand Knives," in Chapter 2. In it, I mentioned that he used two different pentatonic scales in parallel in the main melodic cadences and that although the piece is hardly famous compared to his other worldwide-known works, he considers it a work that established his own compositional style finally at the age of 26, and that ten years after his solo debut with it, just a few months after his Grammy, Golden Globe, and Academy Award victories, he rendered it as the last number in his first recital in New York City in June 1988, proudly on the keytar rather than the keyboard as he usually did. This was in contrast to the fact that when he performed in New York as a member of Yellow Magic Orchestra, he simply played expressionlessly, surrounded by multiple keyboards and machines.

As a side note, the album of the same title with this tune was released in 400 copies and 200 were returned. This means that of the 120 million people living in Japan, only 200 bought and listened to the tune back in 1978. Who could imagine that ten years later he would win a triple crown of prestigious musical awards in the United States?

Incidentally, there is another interesting tune on this first commercial album of his. As the title "Grasshopper" suggests, it is a piano duet depicting a grasshopper hopping in the grass. It is charming. Just looking at the sequence of notes in the main melody, one can imagine a grasshopper hopping through the grass.

♪ LaSoMiLa-TiDoReLaRe(LaDore), MiReLaSoLaTiDoSoDo(SoLaDo)

Although this piano piece, for whatever reason, has not been re-recorded or performed since then, it gives a good indication of his pianistic skills and foreshadows the talent with which he arranges and performs his own compositions for the piano. Besides, there is another interesting thing in it; this melody has one thing in common with the double melodies of "Thousand Knives". It deliberately avoids the "Fa" note of the seven-note scale.

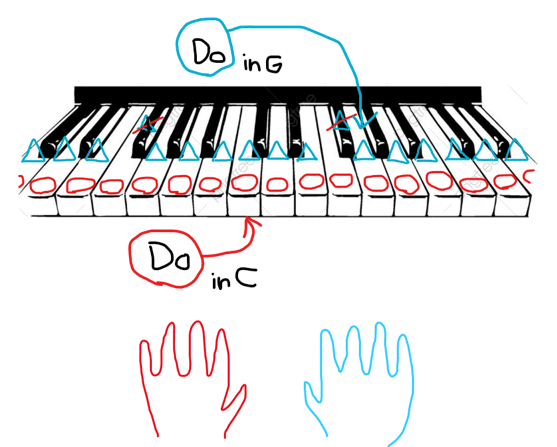

This keyboard diagram shows that the white keys, or the seven-tone scale, contain these pentatonic scales. If we consider these two scales as subsets and make them a combined set, it looks like this.

This shows that there is only one empty set of notes on the white keys, or seven-note scale. There is no "Fa" there. It means that we have only a six-note scale instead of a seven-note scale on the white keys when we depend on these two pentatonic scales. This creates some interesting musical feats.

I will leave the high-minded talk for later chapters; for now, I will explain his unique double pentatonic scale technique. Below is a conceptual diagram of the two parallel pentatonic scales.

There are four types of white keys with triangular and circular markings, and two types with only one of them. Let's make a Venn diagram of them.

Whenever he uses "Ti" or "Do", the elements from the difference sets in the melody, he always compensates them by creating a new set. For example, in the case of "Ti", he adds the "mi, so, Ti" chord (in green) as a new set, making "Ti" a common element of both sets. Other chords like "so-Ti-re" also go well together with it.

For "Do", the "fa-la-Do" chord can be added as a new set, making "Do" a common element of both sets.

Incidentally, "la-do-mi", "re-fa-la-Do", etc. are also acceptable in this case. In short, either "Ti" or "Do", chords with each of them as components (even if they differ by one or several octaves) can be applied as a new set.

Consider this technique in more detail using the first three beats of "Rydeen" as an example.

The note "Ti" on the second beat of the melodic phrase "La, Ti, Do" is accompanied by the chord "mi, so#, ti". In the previous chapter, we learned why the chord "mi, so#, ti" instead of "Mi, So, Ti" for the "Ti" is used in this phrase. This is called a dominant chord in the minor key. Since it is a propulsive chord, it is very suitable for music that expresses the super horse Rydeen galloping through the galaxy, not to mention that since this chord contains "Ti" in its structure, it can be used as an accompaniment chord to the "Ti" in the melody in Sakamoto's original set theory composition technique.

The same tactful explanation works for the "Do" note in the melodic phrase. At this moment, it is accompanied by the "La-Do-Mi" chord, which means that the "Do" of the melodic phrase belongs to this chord.

This unique compositional technique of his will be discussed in more detail in later chapters when we discuss his other compositions and examine how it is applied to them. The point is that, by considering two different pentatonic scales in set theory, he turns them into a six-tone scale while retaining the characteristics and advantages of the five-tone scale.

Meanwhile, if these two pentatonic scales are considered markers pointing to two different keys, respectively, the following interpretation is possible.

This means that the right hand and left hand can also be interpreted as playing seven-tone scales in different keys.

However, this interpretation has a drawback: one of the seven notes available for the right hand is a black key.

Therefore, for convenience, we establish the rule that the left hand can play all the notes of the seven-note scale on the white keys, but only one note on the white keys is not available for the right hand in this way.

In fact, this is a technique used in almost all of Sakamoto's music. The intro melody of "Thousand Knives" and the main melodies of "Grasshopper" and "Rydeen" also employ this technique. There are two main reasons why he like this compositional technique. Firstly, as mentioned earlier, using the hexatonic scale while retaining the characteristics and advantages of the pentatonic scale allows a wider range of melody creation, and at the same time, the available chord progressions remain in accordance with the seven-note scale, allowing the use of established compositional methods in their present form. At the same time, it ensures the identity of the pentatonic scale, which is convenient in many ways, as will be explained later. Sakamoto's music is based on the question, "How does an Oriental maintain his Oriental identity while composing and performing music in a Western-style?" This is related to the more advanced topic of what constitutes modern civilization, and will therefore be discussed in later chapters. For now, I would like to focus on the fact that in Sakamoto's music, melody corresponds to the six-tone scale and harmony to the seven-tone scale in principle, which can be explained in music theory as follows.

Here are two different seven-tone scales. Six of the seven notes from both scales overlap on the white keys, but only one note does not.

This also means that if we don't play that note in one scale, we can avoid disagreement with the other scale. In fact, this is exactly how the notes of "Rydeen" are arranged.

♪La, Ti, Do-, DoReDoTi-TiLaSo-Mi-La-

Incidentally, it could be notated differently as follows.

♪Re, Mi, Fa-, FaSoFaMi-MiReDo-La-Re-

You can see why in the following keyboard diagram.

♪Re, Mi, Fa-, FaSoFaMi-MiReDo-La-Re-

♪La, Ti, Do-, DoReDoTi-TiLaSo-Mi-La-

If the upper and lower pentatonic scales are used as a measure of tonality, then the blue and red scales can be considered as a difference of five degrees. That is if the right-hand plays the upper scale (in water blue) and the left-hand plays the lower scale (in red) in the following keyboard diagram, the right, and left hands can also dance steps in harmony even in different keys.

Metaphorically speaking, this is like a train that rushes at times on the left track and at other times on the right. It can't leave the track, but it can be transferred from one track to the other by someone operating a turnout while it's running. The melody of "Rydeen" is a special Bullet Train rushing at times on one of the two parallel tracks and at other times on the other track, using the chords as turnouts. It does not stop until the end of the line.

This musical feat allows the melody to divert freely along parallel tracks, without ever derailing them. It can also be explained as follows. Here is the keyboard diagram I showed you a few pages ago.

In music theory, the principle of a musical piece is that it should be in one key overall, even if temporary changes in the key are allowed. Simply put, when playing a keyboard instrument, the right-hand and left-hand should be in the same key. However, Sakamoto developed the technique where the overall tonality is not disturbed even though the melody and harmonic progression deliberately differ by five degrees.

This innovation can be seen more clearly in the comparison with "Behind the Mask". As we analyzed in chapter 2, in this piece, the key change technique specific to the guitar is applied to the keyboard instrument. This means that the listeners experience the repetitiveness of the key change. On the contrary, in "Rydeen" the repetition of the key change is not obvious to the listeners. An analogy can be made: a Bullet Train running on the down line switches to the up line, and after a while, it switches back to the down line but the track switching is so deft and natural that the passengers feel that the track is just curving, not switching.

Incidentally, this technique was also used in "Technopolis," another signature YMO tune in Japan, which was included with "Rydeen" on the album "Solid State Survivor" (1979). One of the revolutionary aspects of YMO was the subversion of rock music, where the performers were completely subjected to the mechanical (or we should say train-like) rhythms played by the music sequencer. Sakamoto's compositional techniques fitted well with this YMO methodology. Their full use of electronic devices such as synthesizers, sequencers, and personal computers, as well as their costumes and stage performances that deliberately conformed to stereotypical images of Japan invented by the Westerners, were considered novel by the Japanese public at the time, and the record company they belonged to claimed that this showed how enthusiastically received their music was by the Western market. The Japanese public was so dazzled by the hype created by their record company that there was little commentary on what YMO's true innovations were from a music theory perspective. This is partly because the band members, especially Sakamoto, did not comment very accurately on their compositional techniques, even though they were very brilliant musicians. This is not because they were careless, but simply because they did not have enough words to describe their own creative approach to composition and arrangement.

Again, in exploring Sakamoto's compositions and arrangements, I do not rely absolutely on his explanatory comments on his own compositions, sometimes even denying them altogether, but aim to give definitive answers to long-standing mysteries about his brilliant music explicitly from the set-theoretic approach I have discovered. If possible, I would like to analyze more of his compositions chronologically, but considering that this would increase the page count considerably, I have decided to limit the number of his tunes to be analyzed in this book. At the same time, I would like to state that I am, in principle, critical of previous analyses of his music by other music analysts and musicians, although I will refer to these analyses when considered to be needed. In the next chapter, we will finally take "Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence"(1983), his most widely-known tune in the world. We will devote a few chapters to this as well.