How He Made Thousand Knives

[Continued from the previous chapter] For Ryuichi, "Behind the Mask" (1979) could be considered a frustrating piece in the sense that it was not an artistically or commercially strategic composition but through a chain of luck and coincidence, it was later acclaimed (in the United States) as a masterpiece of rock 'n' roll music. He was then at the age of 27. He felt frustrated that he found it very hard to explain what was rock 'n' roll about the tune even with his brilliant musical mind. Ever since his obscurity, he had an outstanding ability to analyze musical compositions. For instance, when he was involved in the creation of some musician's album, and when the musician wanted to include Klaus Augmann's musical tastes in his coming album, Ryuichi would buy Augmann's records, listen carefully, and analyze and study his compositional techniques, and then amaze the studio staff by applying the knowledge gained to the arrangement of the album's tunes. However, when people asked him about his own music, he sometimes couldn't explain it very well. That explains why he was so confused by the huge response to his "Behind the Mask" in the United States.

Even as for his first commercial work "Thousand Knives" (1978), which was released one year before "Behind the Mask" and later said in an interview helped him finally establish his compositional style, he could not answer well when a music analyst later asked him how he came up with and chose chords that worked perfectly in the musical context but were considered wrong in terms of classical music theory. Indeed, this piece, with which he commercially solo debuted at the age of 26, deviated from classical music theory from its initial measures of the intro.

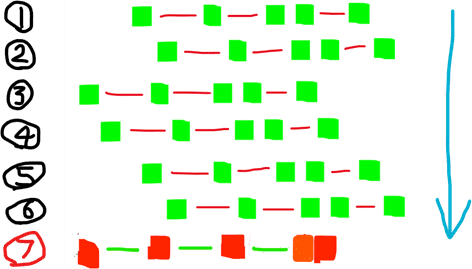

Each of them is visualized on the diagram, as shown below.

Six of the seven are actually sequences of different notes in the same relationship. This is an arrangement of the technique known in classical music theory as "parallel movement of an identical chord," in his own very unique way. (It will be explained in the next chapter.) Incidentally, in my opinion, he was inspired by Darth Vader when he composed this intro cadence.

This is no wild imagination. "Thousand Knives" was composed in a Tokyo studio in July 1978. Just one month earlier the epochal sci-fi adventure movie "Star Wars" was released in Japan. It was an unprecedented film for its time, combining the technology in another galaxy that makes it possible to even exceed the speed of light with a classic adventure story. It was exciting enough to inspire him as a 26-year-old keyboardist and pop music arranger who loved the latest musical technology.

Luckily, there was a recording studio available at that time that a record company allowed him to use. It was designed and built specifically for a legendary Japanese vocalist, and once it was depreciated, one of the studio's recording rooms was offered to ambitious musicians like him for free use late at night. He brought the latest electronic music equipment into the studio with the goal of combining everything that interested him at the time, from reciting Mao Zedong poetry to reggae to Francis Ray to fake Japanese-style folk songs. He spent many hours every night for many weeks finishing his first solo album. It was "Thousand Knives," the same title of its first track.

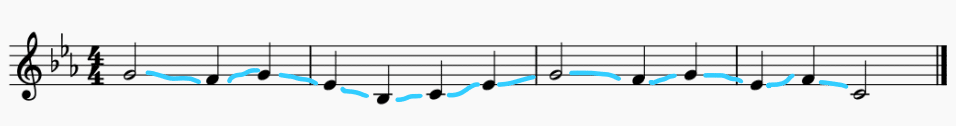

It was almost a study in comparison to his later works, but "Thousand Knives" (and the rest tunes of the album of the same name) showcased a variety of techniques he would later use in his musical career, especially in film music. These details will be discussed in later chapters, but for now let me turn to a technique that would also be used in the main theme of the movie "Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence," which was released five years later. Recall the main melody of "Thousand Knives" introduced at the end of Chapter 1.

♪ Mi_ Re, Mi / Do So La Do / Mi_ Re, Mi / Do Re La

It's a very simple phrase based on a pentatonic scale. Anyone would believe it if they said it was an old Japanese nursery rhyme. In fact, when it was played as the last piece of his first solo concert in New York in June 1988, a full decade after its composition in Tokyo, the backing band and singers sang it as if they were singing along to a Japanese nursery rhyme. New York audiences may have been puzzled by this strange rendition, but for him, the piece was groundbreaking and importantly worthy of being performed in this manner. During the composition process of the tune, he learned that even from a very simple and rough melodic phrase, you can make an impressive tune if the composer has the necessary arranging skills. In the fourth chapter, we will analyze his most famous masterpiece in the world, "Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence", but in preparation, we will briefly review below the main melodic cadence of "Thousand Knives".

For the benefit of those who don't read music, I will give only a brief summary. (Those who can read music, please refer to my blog articles for a more expert analysis). In these four measures, we find the soil and seeds from which the impressive melodic cadence of “Tong Poo,” which he wrote for the first album of Yellow Magic Orchestra one year later, and the famous melody of "Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence" germinated five years later. One of them, needless to say, is that this melodic phrase consists of a pentatonic scale.

Let me briefly explain what a pentatonic scale is. Try playing the melody of the tune "Flea Waltz" on a keyboard instrument. Even if you have never taken piano lessons, you should be able to play it without difficulty, since it is a world-famous tune. Once you do, you will notice that most of the notes of the melody can be played on the black keys. This means that most of the melody is written on a pentatonic scale. It also means that the black keys are in the exact row of keys that corresponds to the pentatonic scale. Incidentally, you can also play this scale on the white keys. Give it a try.

Ryuichi had hesitated to use this scale in his works because he had thought it was too simple and primitive. He had become familiar with the highly intellectual and abstract works of contemporary music since attending Tokyo University of the Arts, and he despised melodies that used this scale. In "Thousand Knives," however, he realized the technique of using two different pentatonic scales in parallel; He had another pentatonic scale melody below the main pentatonic scale melody so that it parallels to the main melody by means of a four-degree interval.

This is Ryuichi's unique technique for simultaneously setting two different tonalities in a single piece, using pentatonic scales as a musical buffer mechanism for this purpose. This not only formed the basis of his first solo commercial work, "Thousand Knives," but has been used in a lot of works of his distinguished career. He, however, is unconscious of this. It is evident from the fact that he did not talk about it in any of the comments he made about his own compositions over the past few decades, and from the fact that he has sometimes failed to articulate his method when music analysts asked him about each piece in terms of compositional technique.

In fact, he had a major weakness in his analytical skills. He had been practicing piano since he was three years old and had been taught to compose by a music professor since he was 12. This meant that he was raised in a highly Japanese academic musical education. He loved Bach, Beethoven, and in particular Debussy. On the other hand, he was one of the usual Japanese boys and girls who spent their adolescent days with the leading western popular music of the time, such as the Rolling Stones and the Beatles. For more than a century, there was a clear bias in the music education of Japan. Since the late 19th century, Japan was eager to introduce and absorb Western civilization and culture in order to maintain its independence in a turbulent world situation dominated by the Western powers. This was also reflected in the musical education of children. In the Western world, there were two systems of note naming, "CDEFGAB" and "Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Ti," or the "fixed Do" and "movable Do" notation systems, and children were taught to use both flexibly. Meanwhile, in Japanese music education, "Fixed Do" notation was emphasized for training music professionals, while "Movable Do" notation was emphasized in the usual school music classes. Ryuichi, who grew up studying music highly academically, received a thorough education in the former system. This was an aural advantage when learning someone else's music, but an extreme disadvantage when analyzing a piece of music unless using the "movable Do" system as well. Instead of being trained to use both systems, he developed musical brain nerves that could analyze a piece of music and produce results only in the "fixed do". This often resulted in his inability to speak correctly about his music.

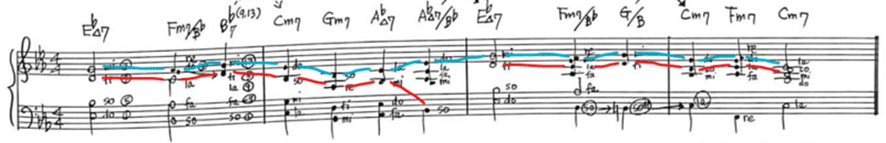

This musical defect of his is also manifested by the fact that he often fails to explain clearly his method of using pentatonic scales when someone asks about it, although he is very skillful at using them in his compositions very well. He, for example, uses two different pentatonic scales in parallel, or, as accounted in the articles on my blog, has several different pentatonic scales arranged vertically and then in parallel in the same cadence to form an impressive chord progression (Refer to the intro to Darth Vader-style "Thousand Knives"), etc. These are very subtle and brilliant. He, however, is unaware of them until a music analyst like me points them out to him, showing a diagram like this written in movable-do notation.

This "movable-do" diagram shows that the pentatonic scale should be interpreted as a five-tone scale that works in both the same tonality as well as in different tonalities. The light blue pentatonic scale is a minor pentatonic scale with A as the “La” note, and the red one is a minor pentatonic scale with E as the La note, meaning that different tonalities can coexist in the same tonality if they are based on the pentatonic scale.

If you can understand this, you can understand what made "Thousand Knives" a milestone for him when he was unknown, and also that it was very difficult for him to explain what made that tune a milestone for him because he didn't have enough musical training in movable-do notation. As will be explained in later chapters, one of the most important things that make his music his own is the fact that the melody and chord progressions are composed in different keys in many cases. It is as if a soprano singer and a tenor singer were singing different songs in different keys simultaneously on the same stage. To put it more figuratively, his music is a perfect partner dance, with the right-hand and left-hand dancing different steps from each other, but from the audience's perspective, it's a perfect partner dance. "Thousand Knives" was his first commercial piece that successfully used this technique. It was not an extremely outstanding piece of music, but when he rendered it as the last number of his first solo show in New York in 1988, exactly ten years after his commercial debut in Japan, it was his way of expressing his pride in the tune and his ten-year musical career that began with it. A few months earlier, he had received a Grammy, a Golden Globe and an Oscar for the soundtrack of the movie "The Last Emperor." He chose "Thousand Knives" as the last number of his first New York concert obviously because he wanted to celebrate himself with his first milestone work.

Now back to 1978. While composing "Thousand Knives," he (unconsciously) developed his own pentatonic scale techniques back then. One of these techniques, in which two same-shaped melodies based on two different pentatonic scales sound parallel and make the whole cadence to which the two scales belong bi-tonal, was further developed in two instrumental pieces the following year, in which the melody moved flexibly back and forth between the two different pentatonic scales. One of them, "Tong Poo," was included on the first Yellow Magic Orchestra album. The other appeared on the next YMO album, with which they received great success in Japan. Takahashi, not Sakamoto, composed the main part, but Sakamoto turned it into the finished work. It was a fearless, avant-garde work. It showed for the first time that the ingenious use of pentatonic scales, which had once been anathema to him, could offer more musical possibilities both commercially and artistically, even though he did not realize it consciously. In the next chapter, we will analyze the representative tune of YMO in Japan, "Rydeen" (1979).