Who Was Gone "Behind the Mask"?

Go, Go, OHTANI, Go!

Every time Japanese professional baseball player ŌTANI Shōhei takes the mound, this song is played in stadiums in Los Angeles, Boston, and other American cities. The classic rock and roll song "Johnny B. Goode" has long been popular in Japan because one of its lines, "Go, go, go, Johnny, go!" sounds like "Go, go, Ōtani, go!" to the Japanese people. Ōtani liked this bilingual pun and chose this tune as the theme song for his pitching appearance on the mound. As a side note, rock and roll evolved by repeating how black musicians were inspired by white musicians' music, white musicians were inspired by black music, black musicians were inspired by white pop music, white musicians were inspired by black musicians' tunes, and black musicians were inspired by songs that white musicians created. In the context of 20th-century U.S. history, it is very interesting that "Johnny B. Goode" is used as a theme song today by Ōtani, who is neither black nor white, but yellow.

Rock 'n' roll has been a difficult music to deal with for most Japanese pop musicians, despite the fact that it has inspired them for many decades. Ryuichi, in particular, is a Japanese musician who is well aware of the difficulty. He wrote an instrumental piece for a TV commercial for the Japanese watch manufacturer SEIKO when he was still unknown outside of the underground world of Japanese pop music. He later arranged it for an album by an avant-garde rock band he joined, with a British lyricist, who was working for a Tokyo radio station, adding English lyrics. Ryuichi wasn't a good singer, especially in English, so he used it to his advantage by singing through a vocoder to make it sound like a robot or alien singing. "That's a mediocre piece for you," the rest of the band joked after the recording was finished. He, too, thought it was mediocre. However, the Japanese record company that produced the Yellow Magic Orchestra later partnered with an American record label, A&M, resulting in a YMO tour project in the United States. Surprisingly, his song "Behind the Mask" was well-received by American audiences. He discussed it in several interviews after they returned to Japan. In summary, "In Japan, the song was not well received. When we performed it in the United States, however, both blacks and whites were captivated. They said it was rock and roll. We, on the other hand, had no idea what they heard about it that made it rock and roll. It appeared to be something that could only be defined by its American cultural, historical, and popular context. It then something that we, as foreigners, are fundamentally incapable of comprehending." One of YMO's objectives was to create carefully analyzed pop music. They were initially confident that if they maintained the position of objectively analyzing different types of music with a computer and synthesizer, they could learn the rhythmic sensibility of foreign pop music, whether it was black music from New Orleans or folk songs from Okinawa. When they encountered a different reaction to their American tour than they had anticipated, it was both a surprise and a disappointment for them. It was a major setback, particularly for a man who was so certain of his ability to analyze and learn any music, no matter how unfamiliar it appeared to him. This is also demonstrated by the fact that he has since stated, "No matter how much I analyze this song, I have no idea what's rock 'n' roll about it."

Tatatatatan, tata

Tatatatatan, tata

Tatatatatan, tata

Tatatatatatatan

This is the basic rhythm of "Behind the Mask." Very simple. Each of the four-beat segments is accompanied by a different simple chord, and they can be repeated indefinitely. In a nutshell, there are four-beat segments and four simple chords. Electric guitars and drums support the vocal as the lead in rock music, so the chords played are usually simple compared to those in jazz. The chord progression in "Behind the Mask" was quite simple. It was seemingly one of the standard chord progressions in rock music. Despite being inspired by rock music, the composer and his fellow musicians believed that the only unique aspect of this song, aside from modulating the singer's voice to sound like a robot or an alien, was its use of synthesizers rather than guitars.

However, when they performed this song in cities ranging from New York to Los Angeles in 1979 and 1980, the audience reaction was unlike any of their other songs. They had the same experience as the protagonist in the 1985 movie "Back to the Future" (in some respect), where a high school student is accidentally transported to 1955 by a time machine. He performed and sang "Johnny B. Goode" at a high school dance. He was overjoyed that not only the young white audience but also the black players who accompanied him were enthusiastic about his song and performance. He created a musical space, albeit for a brief moment, in which blacks and whites could transcend racial barriers and dance to the same beat three years earlier than in real history. He realized that this was the rock and roll miracle. In contrast, the enthusiasm of the American audience for the performance of "Behind the Mask" upset YMO members, particularly Ryuichi. They encountered something they could not understand even with Ryuichi's brilliant ability and skills in music analysis.

Tatatatatan, tata

Tatatatatan, tata

If someone could go to him in a time machine and tell him that this is a very simple rhythmic pattern, but it makes a lot of sense mathematically and physiologically in terms of rock and roll, he would have been very interested in it.

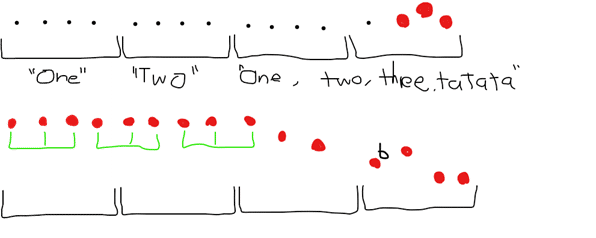

Here's a four-quarter rhythm notated in eight beats.

✓✓✓✓✓✓✓✓

Let's hum it like this: "Tatatatatatatata." It's just a repetitive mechanical sound. Now, let's try to take out one of the checkmarks lined up here, and hum the rest. Take this, for example:

✓ ✓✓✓✓✓✓

"Tantatatatatata." When we hum this, we'll feel a rhythmic self-consciousness in it.

✓✓✓ ✓✓✓✓

"Tatatantatatata." We might feel something like self-consciousness in this also.

✓✓✓✓ ✓✓✓

"Tatatatantatata." And maybe in this rhythm as well.

Let's hum this one too.

✓✓✓✓✓ ✓✓

(Let's call it a rhythmic pattern Ⓐ)

"Tatatatatantata." When we hum this, the scene of a cheerful little child running, bouncing once, and then running away comes to mind. The key to understanding this is that the number of checkmarks in the first half of the row is odd, not even. When a person starts running with the dominant foot and bounces on the dominant foot, the number of steps will be odd. This is elementary math.

However, with the following rhythmic steps, even though the number of steps is odd, the child can bounce but cannot run after landing.

✓✓✓✓✓✓✓_

(Let's call it a rhythmic pattern Ⓑ)

As shown, there is no point in landing after bouncing. Consequently, this rhythmic pattern cannot stand for bouncing and running, but rather an end.

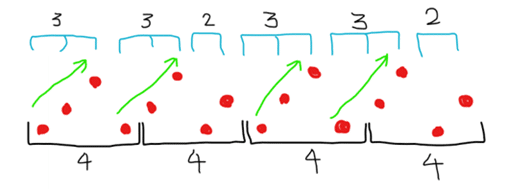

Let's combine these two rhythmic patterns Ⓐ and Ⓑ as follows.

Ⓐ Ⓐ Ⓐ Ⓑ

Let's try humming it this way.

Tatatatatan, tata

Tatatatatan, tata

Tatatatatan, tata

Tatatatatatatan,

This is the fundamental rhythmic sequence repeated in "Behind the Mask" from the beginning of the intro to almost the very end. There's an even more interesting trick to it. Have someone hum this rhythmic sequence, and you try to hum the following rhythm in sync.

ZUN, TAN, TAN, TAN

ZUN, TAN, TAN, TAN

ZUN, TAN, TAN, TAN

ZUN, TAN, TAN, TAN

When the first rhythm sequence and this one synchronize with each other, they create a harmony of beats. The first rhythm is composed of a 3:1 ratio and the second is a 1:3 ratio. In other words, due to the rhythmic contrast between the two rhythms, the center of gravity of the whole rhythm is completely stabilized once they are synchronized. It is as if blacks and whites, though taking different steps, are in total harmony.

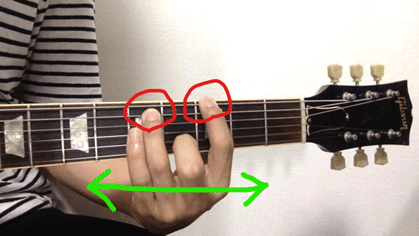

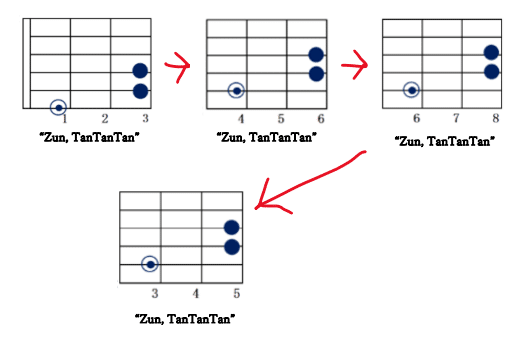

Speaking of the two different things coexisting in harmony for a moment, there is another twist to this piece. I would like you to try playing each of the following four simple chords on the guitar to the rhythm of the humming phrase "Zun, tan, tan, tan" as replacing the chords according to the repeat of the phrase.

These are what guitarists call "power chords". The thing about them is that they are, above all, very easy to play, even for beginner guitarists. These chords are simple and consist of only two notes in five-degree intervals, such as "do-so". Also, unlike acoustic guitars, electric guitars are played loudly through amplifiers and speakers. This means that electric guitarists prefer playing chords with fewer notes so that they don't interfere with the vocals. This, as a result, has helped them invent various simple and exciting chord progressions using these chords, which do not necessarily require complicated fingering.

Ryuichi began taking piano lessons at the age of five, studied Western classical music, especially the works of Bach and Beethoven since childhood, and submitted an orchestral piece as his master's thesis while completing his master's program at the Tokyo National University of Arts and Music. Back then, while working part-time to arrange music for popular musicians and play the keyboard for their recordings, he also applied an academic and analytical approach while learning electric guitar music. Inspired by the extensive band experience of two of his colleagues in the Yellow Magic Orchestra, Ryuichi became interested in the chord progressions commonly used in rock music. He was especially fascinated by those progressions that are easy to play on guitar but are foreign when played on the keyboard. Since he could not play the guitar, he played these foreign chord sequences on the synthesizer. One of them inspired the prototype of "Behind the Mask".

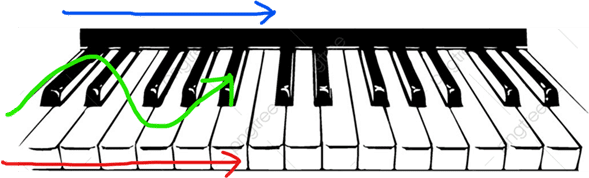

As already mentioned, this piece consists of only four chords, which are repeated in sequence. I have already illustrated the fingerings for playing these chords on the guitar, so below we will look at the fingerings for playing them on the keyboard. Then we can understand why young Ryuichi was so interested in this chord progression.

As shown, the first chord is on the white keys, the second is on the black keys, the third is also on the black keys, and the fourth is again on the white keys. This cycle repeats itself. When you play chords on all the white keys and chords on the keys containing black keys in the same cadence, they often sound pretty eccentric, but in this chord progression, they sound fresh and cool.

Here is the simplest explanation of how this is possible. Classical music theory is in principle based on the keyboard instruments such as the piano, while the strings of the guitar are arranged in a very different way than the piano keyboard. This means that even if a chord progression is considered wrong in classical music theory, it is not unusual that it sounds quite all right on the guitar.

It is uncertain whether he was aware it at that time but it supposedly appealed to him even if he were unaware of it. Classical music theory, which he had studied since childhood, said that a piece of music had to be in one key in principle, and that otherwise it had to be considered to have "changed key" in the middle of the piece. At the very least, it adequately explained Bach and Beethoven's music. At age 11, however, he was enthralled by the music of the Beatles, whose music deviated from the music theory he had studied. He was then surprised, at age 13, to learn from the music of Claude Debussy that ambiguous tonalities were possible in music. Presumably, he sublimated these musical thrills of his adolescence into the electronic song "Behind the mask," using one of the chord progressions that amazed him, with the latest music technology of the time.

If the Goddess of Music had given him and his colleagues a chance to see "Back to the Future" (1985) six years before its actual release year, when they were surprised and puzzled by the enthusiastic reaction of American audiences to the song, they might have gotten a glimpse of what the American audiences perceived as rock and roll in the song, or what rock 'n' roll was to the American people. Marty McFly, the protagonist of this story, is a high school student of Irish descent in contemporary times (1985). By chance, he wanders into his town of 30 years ago. It is a world where the white and black people are socially divided. He happens to attend a high school dance party there. He joins a group of black musicians on stage and plays together "Earth Angel," a very popular Doo-wop song at the time. They are impressed with his guitar skills and ask him to play another song. He plays and sings "Johnny B. Goode," even though the song is not actually released until three years later. Both the white audience and the black musicians were delighted by the tune, which is perfectly unfamiliar to them. Marty is moved, too, to watch his singing and playing excite both blacks and whites. He learns in this moment that rock 'n' roll has grown up in American history to transcend racial differences. It is a musical space where everyone could share the same beat, transcending racial differences for a while. He (or rather, the American viewers of this movie) learns that rock and roll was born and nurtured as a brilliant, musical fruit of a social climate a little earlier than the civil rights movement, which was in the early 1960s, and it would grow up to be over generational.

Hum the electric guitar playing at the very beginning of "Johnny B. Goode."

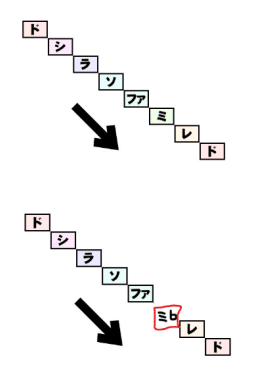

This tune is written in a 4/4 time signature, with four bars forming one cadence. This is also one cadence, or four bars, of the humming of "one, two, one-two-three-tatata" at the beginning of this introduction, but the "tatata" phrase is a triplet of sixteenth-note beats. In other words, the electric guitar jumps with odd steps into a musical world built on even number of steps. Not only that, it then goes down an unfamiliar scale. When going down a scale, Beethoven would come down with "Do, Si, La, Sol, Fa, Mi, Re, Do" with an authoritative, but in "Johnny B. Goode," the electric guitar comes down bouncy with "Do, Si♭, La, Sol, Mi♭, Mi, Do, Do." This scale is different from the one we learn in music class at school. It is based on the Mixolydian scale.

In addition, Beethoven would have been furious if he had heard "E" and "E♭" in sequence in music. In classical music theory, the Ionian scale "Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Si, Do" is called a major scale, and the one in which "Mi" is replaced by "Mi♭" is called a minor scale. Try playing each of these two scales on a keyboard instrument in order.

The first has a bright sound, while the second has a slightly melancholy sound. In music theory, they are called "major" and "minor," respectively. The "Mi" note symbolizes the major key, while the "Mi♭" symbolizes the minor key. In this piece, however, which Marty McFly played for high school students in 1955, the "Mi" and "Mi♭" appear in turn. With this device, his guitar skillfully jumps the line between major and minor keys. Nevertheless, the music sounds consistent. At a dance party hosted by the high school, he played this song, and both whites and blacks got a kick out of it. When these opposites-odd and even beats, major and minor, Ionian and Mixolydian scales-completely coexisted in the musical language, the music was accepted by whites and blacks alike as music that erased racial differences with a single electric guitar note. This was rock and roll.

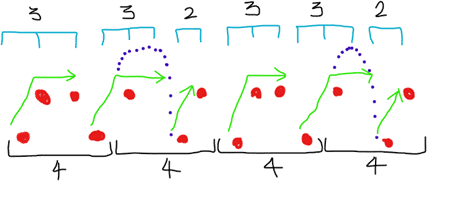

Back to "Behind the Mask". This tune, like "Johnny B. Goode," is a juxtaposition of multiple dichotomies. On a previous page, I mentioned that the chord progression in this piece move back and forth between two different tonalities like a fish. In "Johnny B. Goode," the electric guitar moves between two tonalities which are different, to use a musical term, by the major second degree. In "Behind the Mask," the synthesizer keyboard also moves between different tonalities that vary by the major third. There are also similarities in the way these two pieces switch momentarily to the minor key and then back to the major. (Please refer to my blog for a more in-depth analysis of how this is achieved). Here is a phrase that is repeated from the introduction of "Behind the Mask". (Sub-melodic phrase Ⓐ)

Here is a sub-melodic phrase Ⓑ. It has the same rhythmic pattern as the one discussed on the previous page. It starts four bars after the sub-melody Ⓐ and repeats in sync with it. The one-note blank in the melodic phrase corresponds with the beach volleyball flying through the air.

Check my blog for a detailed explanation of the rationale for choosing the notes that make up the sub-melodies Ⓐ and Ⓑ. Odd-based and even-based beats, major and minor, and two different scales (in this case, two different tonalities); these opposites coexist perfectly in this piece. This dynamic stat stimulates the performers and the audience to try to improvise various rhythmic patterns and melodies and keep them stable in turn at the same time. Marty's "Johnny B. Goode," played on electric guitar induced improvised dance steps by high schoolers at the 1955 party. This can explain why "Behind the Mask" also thrilled the American audience when the Yellow Magic Orchestra performed in cities across the United States in 1979 and 1980. "These yellow musicians are playing rock and roll for us with the latest Japanese electronics! Oh, what a Yellow Magic!"

When A&M Records released an album by YMO (or an American re-edit of that album) in 1980 under the partnership deal with Alpha Records in Japan, it released "Behind the Mask" as a single to promote the album. Although the album was praised by some critics, it was not a sales success, but the tune piqued Quincy Jones' interest. At the time, he was working on Michael Jackson's next album. Michael liked the song so much that he wrote his own additional lyrics and sang it with a new melody. If the tune had been included on his 1982 album "Thriller," it would have become an iconic tune known in the world of pop music as the signature tune of Yellow Magic Orchestra - or that of Ryuichi Sakamoto. This did not happen, as Michael's copyright agent and Ryuichi's copyright agent disagreed over whether Ryuichi would be allowed to listen to the "Behind the Mask" arrangement for the album before its release. It is unknown whether Ryuichi regretted it when he later learned that "Thriller" eventually sold over 70 million copies worldwide. Some facts that we can confirm today are as follows: Greg Phillinganes, who was then playing the keyboard in Michael's backing band, sang and performed Michael's version himself, and made the official music video. His musical friend, Eric Clapton, also sang, performed, and released the song; and Ryuichi hired another black vocalist to have him sing the same version as Greg's in his live performance. Then, in June of 1988, three months after winning the Academy Award for Best Original Composition for the soundtrack to "The Last Emperor," he played the tune with that black vocalist as an encore at a show in New York City, which ended with a standing ovation.

In April 1990, he chose New York as his residence place and moved from Japan to the U.S. with his family. This was because he anticipated receiving job offers from across the Atlantic in Europe as well, but American filmmakers saw it as him not wanting to be a resident of the Hollywood community, despite winning an Academy Award for Best Original Score. Subsequently, he was expected to win a few more Oscars, but that did not happen. He also did house music and tried to break out as a New York pop musician. But he soon realized that even for someone like him who had developed an extraordinary ability to analyze and perceive everything from a young age, the pop music of this country was not for a foreigner who had not grown up immersed in the cultural, historical soil and background of the country, or at least not without finding an extremely good producer, even if he was the brilliant composer of "Behind the Mask." "Like a candle slowly dying out, my ambition faded," he said in a lengthy interview published online in Japan on Christmas Eve 2021. "It was a dream I could only have had when I was in the Tokyo of the time." If we think about it, it was an unusual situation that one-sixth of the world's money flow was concentrated in Japan at that time. Subsequently, he just kept his presence as one of the most talented musical inhabitants of the non-mainstream music market, with a certain percentage of presence in every region of the world. His musical career, in other words, coincided with the decline of Japan the superpower for decades ever after he moved to and resided in New York City.

Incidentally, when we watch the video of his first live performance as a solo musician in New York (June 1988), we see that before he performs "Behind the Mask" as an encore, he performs a Japanese folk-like song as the last number, with his backing band members smiling together then playing and singing the melody. If you grew up in Japanese elementary school, you probably know this fun song that teases someone in the classroom. "いけないんだ, いけないんだ, 先生に言っちゃお" (You messed up, you messed up! We'll tell the teacher what you did!)

Ryuichi's last number, performed live in New York City, recalls this simple Japanese song. In an interview, he said, "I think this is the song that deserves the name of my real first work." Indeed, the title "Thousand Knives" is provocative, while the tune is so simple that anyone would believe it if they were told it was a Japanese nursery rhyme. What about it made him finally establish his own compositional style at the age of 26, shortly before he started doing YMO? We will look at this in the next chapter.