The Huichol, a Mexican native tribe

You can read the entire article for free.

contents

Overviews of the Huichol tribe

Wixarika arts and their worldview

Pilgrimage and the desert

Ceremony and community

Shamanism and medicine men

Mineral veins and the nature

Caution: The general use of psychoactive plants is restricted by laws in each country. This article does not encourage the use of these plants.

Overview of the Huichol tribe

the Huichol tribe and Mexico

The Huichol are one of several indigenous groups in Mexico. They currently live in a rather isolated manner, high in the mountainous regions that cross the states of northern Jalisco, Nayarit, Zacatecas, and parts of Durango. They have preserved their ancient customs to this day and take great pride in doing so.

The Huichol are one of the few indigenous groups that have been able to maintain their "purity" since the Spanish conquest era. They call themselves "Wixarika" or "Wixáritari" (plural or also refers to their community).

The term "Huichol" is a name given to them by the Spanish, and the Wixárika people themselves do not understand why they are called by this name. Even today, people other than the Wixárika continue to call them Huichol, and there is an undeniable sense that this is a name arbitrarily imposed upon them. Could it simply be a mishearing?

Generally, the majority of Mexicans are Mestizo (generally referring to people of mixed European and indigenous descent, but in reality, it includes people of mixed descent, including Africans brought in as slaves and later Asians in Mexico). This is a term that often appears in textbooks when discussing the differences between North America and Latin America. Setting aside the question of whether they are truly mixed (some Mexicans are fair-skinned or have predominantly European ancestry), it can be said that the majority of Mexicans share an identity under the broad category of "Mexican". However, there are still numerous indigenous minority groups in Mexico, including the Wixáritari (Huichol), whose identities differ significantly from the majority population.

The Wixarika and colonized by the Spaniards

The Wixarika people (from now on, the name I will predominantly use in this article) lived in flat and fertile lands at lower altitudes, not in the high mountains where they currently reside, until the arrival of the Spaniards. (*1) While many indigenous people at the time accepted the Spanish and interacted with them, eventually leading to racial mixing, the Wixarika people rejected the Spanish and chose isolation. To preserve their traditions, they migrated to the high mountain areas—essentially, to less hospitable territories.

In this way, the "purity" of the Wixarika is not just about maintaining their bloodline, but also about preserving the culture and traditions that existed before Columbus discovered the American continent. Their traditions encompass language, religion, rituals, pilgrimages, songs, mythology, art and so on. I am deeply moved by the fact that their traditions have been passed down and that we still have the opportunity to learn about them. I am grateful that their cultural heritage has survived intact until our time, allowing us to witness and appreciate their rich cultural legacy.

Even though the historical contexts are entirely different, this reminds me of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan people's history. There is a common thread in how they chose isolation in mountainous highlands through non-violence and passive resistance, which ultimately enabled the preservation of their traditions. However, the cultural difference between Christian culture and Wixárika culture is fundamentally different from the difference between Chinese and Tibetan cultures.

Wixarika arts and their worldview

Wixarika arts

Speaking of Huichol arts, some of you may have seen them before. For example, there's the Yarn Painting ("Neakritzin" in Wixárika language). In Kenzaburo Oe's work "Listening to the Trees of rain" (specifically the section about the hanged man), there is a story about yarn paintings that were gifted to him when he was in Mexico City in the late 1970s. (From the Shincho publish company "Women Listening to 'The Tree of Rain'")

Yarn Paintings, created by gluing colorful woolen threads (yarn) of various colors onto wooden boards, express the Wixárika's mythology, worldview, and visions experienced during their rituals. These artworks represent a remarkable example of how the pre-Columbian indigenous worldview of the Americas has been preserved and continues to be expressed through art, creating a deeply moving artistic form that resonates to this day.

They also create shoulder bags woven with yarn, which can be considered an art form in their daily use. Additionally, they create various items using small beads called "chaquira". These include decorative accessories like earrings, bracelets, and necklaces, as well as figurines of animals such as deer, jaguars, and hummingbirds, and masks. Similar to yarn paintings, they glue these beads to wooden boards to create artwork. They also weave beads with thread into fabric, creating items like caps and shoes.

Their art features ethnic motifs and predominantly uses vibrant primary colors. The motifs often include animals and objects of spiritual significance such as deer, eagle feathers, peyote (the hallucinogenic cactus), Muwiéri (sacred staff), Jícara or Hikara (containers made from dried gourd), candles, sun, moon, eagles, corn, hummingbirds, snakes, scorpions and so on. These elements are particularly prevalent, representing items used in their rituals and animals considered sacred in their culture.

Their traditional clothing (especially for ceremonies) is hand-embroidered, and they also have shoulder bags and small ritual accessories. Additionally, they create "Tzicuri" (Ojo de Dios or "God's Eye"), which are like spiritual talismans or protective charms from their spiritual world.

Wixarika’s worldviews

A worldview (cosmovision) can be described as the myths, traditions, and religious perspectives of a culture that profoundly influence the community's living patterns and social structure. In the case of the Wixárika, their worldview significantly impacts their artistic expressions as well.

Origins in Darkness

According to Wixárika mythology, in the beginning, the world was enveloped in darkness, and light did not exist. This void became the stage upon which the gods who would give form to the universe would appear. (2*)

In the Wixárika worldview, world creation occurred in Wirikuta. Wirikuta is a sacred site located in San Luis Potosí State, Mexico. Their mythology explains that it was there that the sun was born and the world's creation began.

Major Wixárika Deities

Tatewari: The Grandfather of Fire, one of the primordial creative forces who created the first humans.

Tayaupa: The Father of the Sun, who brings light and heat to the world.

Tatei Haramara: The Mother of the Sea, symbolizing fertility and water, which are essential to life.

Kauyumari: The Blue Deer, who functions as a spiritual guide and represents the connection with nature.

The Process of Creation

The deities gave the origin of life and created corn, animals, and plants through rituals and offerings. This act of creation is not seen as a single event, but rather as a continuous process in which the Wixárika actively participate through their rituals.

Flood and Regeneration

This mythology also includes a great flood that covered the world. After this event, the deities restored order and made the regeneration of life possible. This regeneration symbolizes the eternal cycle of life and death within the Wixárika worldview.

The Wixárika culture is deeply spiritual, rooted in the relationship between the natural and spiritual worlds. Their worldview is based on the belief that the world was created and is sustained by deities and spirits inhabiting every natural element—the sun, moon, animals, and plants. The Wixárika people believe that maintaining balance with these elements is essential for the well-being of themselves and their community.

Pilgrimage and the desert

Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage is a journey to sacred sites that the Wixárika continue to undertake annually. It is part of their rituals and traditions that connect their worldview, and actual daily life, also community and individuals —an ongoing practice that extends from their creation mythology to the present day. One of the key purposes of this pilgrimage is to gather Hikuri (Peyote) for ceremonies performed in their own villages (communities). The journey covers a distance of over 550 kilometers one way.

Five Sacred Sites of Wixárika Culture

Haramaratsie: Western site. The sea in Nayarit State, San Blas. The place where the first Wixárika ancestors appeared.

Te’ Akata: Central site. A sacred cave in the Huichol Mountains.

Xapawiyemeta: Southern site. Scorpion Island in Lake Chapala, Jalisco State.

Hauxamanaka: Northern site. Cerro Gordo hills in the mountain ranges of Durango State.

Wirikuta: Eastern site. A specific location in the desert of San Luis Potosí State, and Quemado Mountain near Real de Catorce.

These sites form a rhombus-shaped cross, determining the four cardinal directions and the center of the Earth—essentially mapping out the directions of the universe. This is a symbol of Wixárika cosmogenesis, and its form connects to the Tzicuri (God's Eye), which signifies the "power to see and understand the unknown". The number 5 holds significant importance in their mythology, representing the five directions of the universe, five sacred sites, five cosmic hunters, and five corn goddesses. (3*)

Sacred site of Wirikuta

As mentioned earlier, according to Wixárika mythology, Wirikuta is the place where the sun was born and world creation took place. It is considered the dwelling place of the most important deities and the equilibrium point of the universe. Every natural element in Wirikuta—its stones, plants, and animals—is regarded as sacred.

The final destination of their annual pilgrimage is Wirikuta, known as "Nana’iyary" (meaning "the path of the heart"). Here, participants perform rituals, collect peyote (Hi’ikuri), strengthen their connection with the sacred, and give offerings to maintain the balance of nature. The ceremonies in Wirikuta are fundamental to Wixárika culture. They include prayers, songs, and rituals that honor the gods and the spirits of their ancestors. These acts are both a form of worship and a means of transmitting their history and cultural values to new generations.

It is fascinating that their prayers are rooted in a belief of maintaining balance not only for themselves but for other people around the world, and everything on Earth. This could be described as the fundamental purpose of continuing their pilgrimages and ceremonies. The pilgrims collect peyote to bring back to their villages, where they will conduct ceremonies with their community members. This act is also a form of service to and connection with their community.

Setting aside the Wixárika’s spiritual beliefs and their view of Wirikuta as a sacred site, this region possesses a unique ecosystem with remarkable biodiversity, particularly in terms of cactus species. It is considered one of the most ecologically rich areas in the world in terms of endemic flora and fauna, standing out not just culturally, but also for its ecological significance. It seems unlikely that this location being a Wixárika sacred site is merely a coincidence.

In recent years, Wirikuta has been facing threats due to the transfer of mineral resource mining rights in the region. I will explain the efforts of the Wixárika people to protect their sacred land and the surrounding environment in a later chapter.

Ceremony and Comunity

Wixarika villages

As mentioned earlier, the Wixárika people moved to their current locations and established their villages to avoid the influence of Spanish conquistadors and Christian missionaries. In their efforts to protect their beliefs, culture, and means of survival, they have a history of maintaining their villages in their own unique way to preserve their distinctiveness. The villagers are members of communities composed of these villages, with each individual having a specific role. Their connection goes far beyond what we might understand as ethnic unity—it is a deeper, more intricate form of communal belonging.

Wixarika are divided into a several major regions, each with a Tukipa (Centro Ceremonial, or ceremonial center). In each village of these regions, there is a designated place where people gather to perform ceremonies. (4*) The regions are Santa Catalina Cuexcomatitlán, San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán, San Andrés Cohamiata, Tuxpan de Bolaños and Guadalupe Ocotán, and there are additional ceremonial centers in other areas as well. In these centers, villagers gather and perform rituals using Hi’ikuri (peyote) that pilgrims bring back from the desert.

In this way, the ceremonies performed in these villages serve not only to maintain traditional beliefs to be passed down to future generations, but also to deepen and reaffirm their sense of community connection.

The concept of "Nierika"

There is a concept in the Wixárika language called "Nierika", which describes their beliefs, spiritual world, the visions received during ceremonies involving Hi’ikuri (peyote), and the artistic expressions emerging from these experiences. By explaining this concept, I believe we can indirectly illuminate the essence of their ceremonial practices.

First, the term Nierika refers to a symbolic representation in Wixárika art (yarn paintings, embroidery, beadwork, etc.) often depicted through multiple concentric circles. According to the ethnologist Mariana Fresán Jiménez in her book "Nierika—A Window to the Ancestors' World" (5*) says

"The basic formal characteristic is a circular object or figure that either has a hole in its center or includes a form that mimics this void.”

"The central hole in a Nierika is a bidirectional observation window, where on one side it enables the deified ancestors to view the human world, and on the other side it allows the Marakame (shamans) to communicate with those ancestors.”

As I will elaborate later, in the Wixárika language, the role translated as 'shaman' is called Marakame. They create Nierika as ritual tools, and these are considered 'mirrors' through which they establish connections with their ancestors and the wisdom passed down across generations. Nierika is more than just an object; it is a gateway between the visible and invisible worlds. Moreover, it symbolizes the center of the universe and represents the sacred connections between all living beings.

Moreover, Nierika signifies the 'ability to see' and refers to accessing the 'vision of deified ancestors', which is achieved through initiation rites. After rigorously maintaining traditional customs, undertaking pilgrimages, and preparing through fasting, sacrifice, and purification ceremonies, the sacred peyote is ritually consumed, enabling the attainment of Nierika. Through this process, one can understand the hidden, enduring, and essential states of things and beings. In this way, the mythical and timeless world of the ancestors is created and experienced.

In this way, the Marakame may also guide everyday matters and important decisions within the community by interpreting the visions and revelations received during ceremonies

Yarn and bee wax on the wood board · 122 x 244 cm · Collection of the National Museum of Anthropology · INAH

Shamanism and medicine men

Marakame

Ma’rakame (or Maraakame) is the term in the Wixárika language that refers to a shaman, which means 'the one who knows' or 'the one who sees (with ability)'. This reflects their capacity to access knowledge and visions that transcend everyday experience.

The Marakame plays a crucial role in the Wixárika community, as they are considered intermediaries between the human world and the spiritual realm.

They possess deep knowledge of the Wixárika worldview, beliefs, myths, and sacred rituals. They are well-versed in sacred plants, particularly peyote, which in the Wixárika language is called 'Hi’ikuri', playing a central role in their religious ceremonies. The Marakame seeks to connect with gods and spirits, gain knowledge, and heal people through the consumption of peyote. This method is sometimes described as 'traveling in the realm of dreams'.

They also serve a role similar to that of a Medicine Man (or Medicine Woman) in other cultures, possessing expertise in healing plants and herbs that can treat various illnesses and symptoms within their village. They prescribe these as medicinal treatments. 'Purification' is another distinctive characteristic of their practice. Using bird feathers (in a Muyeri, or staff) and tobacco smoke, they remove the cause of disease and 'impurities' from people through prayers, which is another significant role within their community.

Moreover, the role of the Marakame extends beyond the spiritual realm to include significant social and community functions. They provide guidance and advice to people on important matters, resolve conflicts, conduct ceremonies and rituals, and protect Wixárika traditions and culture. Their wisdom and experience are deeply respected within the community.

The spirituality of the Wixárika and the practices of the Marakame have been transmitted from generation to generation over centuries. However, due to the influences of the modern world and social changes, Wixárika traditions and culture are facing challenges in maintaining their purity. Nevertheless, the Marakame continue to play a crucial role in protecting the cultural and spiritual identity of their people.

Mitotes

Mitote is a traditional ceremony performed by the Marakame. This ritual is central to Wixárika spiritual practices and serves various purposes, ranging from healing to celebrating community events.

Song and Music: A distinctive feature of Mitote is its continuous chanting. The Marakame leads the ceremony through songs that narrate sacred stories and connect with the gods. Traditional instruments such as drums and other percussive instruments, and particularly the distinctive sound of the violin, typically accompany these songs.

Dance: During Mitote, participants dance in a circle around the central fire. This dance is a form of prayer in motion, serving as a means to connect with the gods and the spiritual world.

Peyote: In some Mitote ceremonies, peyote, a sacred hallucinogenic plant, is consumed as a sacrament. Peyote is believed to open the doors to spiritual dimensions and enable more direct communication (Nierika) with the gods.

Community: Mitote is a collective practice that strengthens connections among Wixárika community members. It provides an opportunity to pray together, share stories, and reinforce collective identity.

Healing: Mitote often includes healing elements. Under the guidance of the Marakame, healing rituals are performed for individuals and the entire community.

Life Milestones: Mitote is also performed to bless significant life events such as birth, marriage, and transitions to adulthood.

Mineral veins and the nature

The nature

As previously mentioned, the Wirikuta region hosts an incredibly unique ecosystem. Forming part of the Chihuahuan Desert, it contains the most concentrated and diverse collection of cacti on Earth per square meter. While deserts are typically imagined as barren landscapes of sand and dunes like the Sahara, Wirikuta is more akin to a pristine, natural garden.

Most cacti in Wirikuta are listed in Mexico's Official Standard for Endangered Plant Species (Norma Oficial Mexicana). The majority of its flora and fauna are endemic, meaning they exist exclusively in this region.

The Golden Eagle, a national symbol of Mexico, drawn on the national flag, inhabits Wirikuta and is at the top of the National Species Protection Program list.

Nature reserve

In 1989, a group of Wixárika pilgrims appealed to the then-President of Mexico to protect their sacred site, ensuring their right to pilgrimage to Wirikuta and the use of Hi’ikuri (peyote) and other sacred plants and animals for their ceremonies.

In 1994, an environmental protection movement led by Wixárika farmers, in collaboration with other social activists, opposed a highway construction project planned to cross the region. As a result, on September 19, 1994, the first protection decree was issued by the government of San Luis Potosí state.

In 1999, a management plan was developed with funding from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Additionally, UNESCO recognized Wirikuta as one of 14 sacred natural heritage sites worldwide under its "Protection of Sacred Natural Sites" program.

On June 9, 2001, the government of San Luis Potosí declared Wirikuta and its historical-cultural routes as a "Sacred Natural Site".

The Wirikuta Biosphere Reserve covers 191,504.363958 hectares, representing just 0.3% of the entire Chihuahuan Desert, yet it harbors remarkably rich biodiversity.

In this ecosystem region, 56% of the 250 bird species are present, including 2 endemic species, 5 endangered species, 1 critically endangered species, and 7 species under special protection.

53% of the 100 mammal species from the entire ecological region inhabit this area, including 6 endemic species, 7 endangered species, and 2 critically endangered species.

14.5% of the 345 cactus species from the Chihuahuan Desert grow in this area, including 12 endemic species, 4 endangered species, 1 critically endangered species, and 9 species under special protection.

These data clearly illustrate that Wirikuta is a truly special region, demonstrating its exceptional ecological significance through its remarkable biodiversity. (6*)

Open pit mining

The Mexican government, through the Mexican company Real Bonanza SA de CV, granted at least 22 mining concessions to the Canadian company First Majestic Silver Corp in the Real de Catorce region. 70% of the 6,326.58 hectares of land with these mining rights are located within the Wirikuta Protected Area.

Open-pit mining, also known as surface mining, refers to a mining development process conducted on the earth's surface rather than underground tunnels. Open-pit mining removes the surface layer where plants and animals live to access even low-grade but extensive mineral deposits. With today's large excavation machinery and explosives, entire mountains can be removed and crushed in a remarkably short time. This process creates massive holes spanning over 100 hectares, typically reaching depths between 200 and 800 meters. Such open-pit mining developments have been critically noted for causing severe environmental damage.

In Canada, open-pit mining has been prohibited due to environmental pollution concerns. However, First Majestic Silver Corp, the Canadian company granted mining rights by the Mexican government, can exploit this cheaper development method in Mexico due to the lack of strict regulations. This scenario reveals a clear problem of political corruption and collusion between politicians and large corporations, where economic interests are prioritized over environmental protection and indigenous sacred lands.

In Mexico, apart from a symbolic fixed fee per hectare, no taxation of any kind is imposed on the mining industry. Similarly, neither the quantity of minerals extracted nor their commercial value is taken into account; only the area of land granted for mining rights is considered. As a result, there are insufficient measures to address environmental compensation or damages from this perspective.

In the mining areas near Wirikuta, veins of silver, gold, copper, antimony, and zinc are reportedly present.(*7)

Underground water

Two processes are used to separate metals from the excavated soil,

Cyanide Leaching Method - This involves piling the excavated soil in large stockpiles and spraying them with a solution of cyanide compounds (potassium cyanide) and water to extract the metals.

Xanthate Flotation Method - This involves placing all excavated material in large settling pools filled with water and xanthate solution (one of the highly toxic chemicals), causing the materials to float.

These methods are used to extract metals, but they are critically problematic due to their serious environmental impacts.

According to the National Water Commission's report, the massive amounts of water used in large-scale mining will cause the depletion of water bodies in this region, which already have extremely low recovery capabilities.

Large-scale mining development consumes approximately 100 million liters of water per day, which is equivalent to the water consumption of an average 150,000 households. Moreover, extracting just 1 gram of gold requires 2 tons of water.

In the arid Wirikuta and surrounding desert regions, underground aquifers are deep, and the water in their deepest layers is not replenishable by current rainfall. Instead, this water is from a much older geological era. In essence, water that predates human history is being extracted.

Of course, the water discarded from large-scale mining operations poses a significant risk of contaminating the sacred springs where Wixárika people collect their holy water, as well as the local community's drinking water, through cyanide, xanthate, and heavy metal pollution.

There are additional mining concessions adjacent to and within the influence zone of the Wirikuta Protected Area. One example is the Santa Gertrudis Dam (in Charcas municipality), where according to the National Human Rights Commission's interviews, exploration is being conducted to a depth of 1,000 meters. This poses a significant risk to the Venegas-Catorce aquifer, which is fundamental to Wirikuta's ecosystem. As a result, this would directly impact Wirikuta's water systems, flora, and fauna.

Mining industry

In 1770, mining activities seemed to be emerging in this region. (*8) Mining operations truly gained significance in 1778, when Bernabe Antonio de Cepeda, a miner from Matehuala's Ojo de Agua, discovered the emergence of a major ore vein and opened the "La Guadalupe" shaft, where large quantities of silver were extracted.(*9)

In 1803, the annual production from the Real de Catorce mines reached 92 tons of pure silver, representing 16% of Mexico's total silver production, making it an extremely significant mining site.

During the last 55 years of the colonial period, when Mexico was still called Nueva España, four significant mining towns existed in Wirikuta area. Among these, Real de Catorce functioned as the central economic hub of the region. Its impact led to a population boom and the development of various related economic activities. In this area, over 100 mines and 56 smelting facilities were in operation.

However, this prosperity lasted only 55 years. As the mineral veins were depleted, people left, leaving behind a ghost town and an irreparably damaged environment and its resources. The trees cut down for water and firewood used in smelting never returned the landscape to its original state. Records describing the natural landscape of this region from 1772 and 1827 exist, and these two texts vividly illustrate the extent of this dramatic devastation.(*10)

Even during this period, without the use of modern heavy machinery or large-scale explosives, such environmental destruction occurred. The difference in environmental impact would be immeasurable additional to the pollution issues caused by the use of modern chemical substances.

Citizen resistance movement

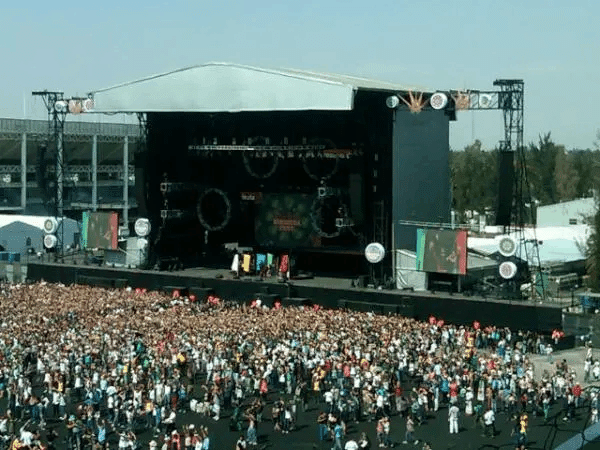

The "Wirikuta Fest" organized by the artist collective “Aho” in Mexico City in 2012 was a large-scale concert that drew over 50,000 spectators to raise awareness, collect funds, and protest against the threat to the Wixárika people's sacred territories by mining projects and agricultural industries. The event was simultaneously linked to the struggle of tens of thousands of young people who took to the streets, dancing, singing, and demonstrating their anger.

The Wirikuta Fest featured internationally recognized musical groups and artists, including Calle 13, Café Tacvba, Julieta Venegas, Enrique Bunbury, Ely Guerra, Lenguaalerta, the Wixárika (indigenous) group Venado Azul (Blue Deer), Caifanes, and Sonido Mestizo.

"Sacred territories are indivisible," stated Máximo Muñoz, representative of the Nayarit Regional Council and the "Wirikuta Defense Front" during the festival. Regarding the government's announcement, he declared, "This is a mockery and an insult. It is a disguised act meant to give the appearance that Wirikuta is free from mining development." He further warned that this action, carried out without prior consultation with those involved, "will only further strain the relationship between us and the government.”

The gathering of Wixarika’s spirutal leaders

Typically, the people who constitute the ritual spaces of each village conduct their pilgrimages on their own times and dates. However, in 2012, all of the Wixárika communities decided to simultaneously arrive in Wirikuta and spend the ritual night together. Arrow carriers and spiritual cup (Jicara or Hikara) bearers, the Marakames, from 17 different villages (including Jalisco, Durango, and Nayarit), carried out the traditional pilgrimage to Wirikuta and gathered at the Quemado Hill.

During this great pilgrimage, the Wixárika people gathered together for the first time in their history, with all of the village Marakames and spiritual leaders convening to defend Wirikuta. This became an opportunity for the entire Wixárika community to unite for a single purpose, by drawing upon the tools and ancestral knowledge provided by their spiritual tradition, and by studying and valuing their culture while facing threats to Wirikuta.

This traditional gathering to evaluate current circumstances and issues (a council of sages) has been conducted within Wixárika culture through specialized individuals most appropriate for each specific domain. However, the meeting of all Wixárika spiritual leaders together has never been remembered to have occurred before. This unprecedented assembly will be remembered as a demonstration of Wixárika unity, carried out with the singular purpose of protecting Wirikuta

Sense of values

People living in villages and towns near Wirikuta cannot engage in irrigated agriculture, nor do they have any significant industry. Around the town of Real de Catorce, there is some tourism, but otherwise, there are virtually no industries that could be called substantial. Some people view the arrival of foreign capital's mining industry as a potential improvement in their living conditions. Otherwise, a large number of people leave their families to seek work elsewhere.

I have been writing about the cultural, mythical, and religious values of the Wixárika people. The values of local Mexicans living in poverty are quite different, and as a traveler like myself being drawn to Wirikuta, this can also be a catalyst for considering our own perspectives. Recognizing this place as a special location with numerous endemic species should indeed be considered one of humanity's values towards nature.

Around the time news spread that the Mexican government had granted mining rights to a Canadian company, I reunited with a marakame I had previously met. He was adamant—and remains adamant—that they must prevent the environmental destruction of their sacred land by these corporations. This struggle, he explained, is not just a battle between the indigenous people and the Mexican government, but also about informing the world and appealing to international institutions like the UN, hoping that global public opinion can correct the government's and corporations' misconduct and environmental destruction.

When I heard these messages about their desire to protect their sacred land and place of prayer, I felt compelled to take action on this issue—not only for Wirikuta and Wixáritari culture, but as a way to spread the spiritual messages I have received, like ripples extending outward to others.

Rather than allowing the experiences from ceremonies and prayer spaces to remain confined to those specific moments and unique circumstances, if these experiences can provide insights that are absorbed and integrated into everyday life, and if they can influence those around us and our environment, then they become truly "tangible" experiences. Such experiences feel like prayers that can truly "reach" something or someone. I even sense that this is what it means to be psychedelic.

If my actions can create even a small ripple of opportunity for myself, my family, and those around me to gain awareness through ceremonies and prayers, and if these can help protect sacred lands and the environment for future generations, I would be happy to start doing what I can, step by step. It is truly precious that the marakame creates spaces and situations for traditional prayer methods and shares them with us. Their chants are incredibly powerful. They sing and perform in ways designed to make their prayers reach further and deeper.

Possessing gold and silver, and acquiring wealth, is certainly one perspective. A poor villager wanting work, even if it's dangerous and potentially harmful to their health, is also a viewpoint. However, I would like to spread the joy of sharing a different value—not the gold and silver that cause environmental destruction in the desert, but the prayers with cacti that open hearts and provide awareness, with people who can dance together with smiles. I want to demonstrate this not just through words, but through actions. Perhaps it's not logical thinking or words, but the direct experience itself that might spark transformation.

Annotations

(*1)Ochoa García, Heliodoro (abril, 2001). «La organización territorial huichol» Weigand, Phil y Acelia García, 2002, “La sociedad de los huicholes antes de la llegada de lo españoles”, en Phil Weigand (coord.), Estudio histórico y cultural sobre los huicholes, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, pp. 43-68.

(*2)López de la Torre, Rafael, El respeto a la naturaleza…, 18

(3*)https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/americania/article/download/1718/1542/5969

(4*)Neurath, Johannes, “El tukipa huichol: microcosmos y macrocosmos”, en Alicia M. Barabas

(5*)Nierika - una ventana al mundo de los antepasados, Mariana Fresan Jimenez, CONACULTA-

(6*)//www.conanp.gob.mx/anp/consulta/EPJ Wirikuta_ 12oct polign 194 mil csi.pdf Estudio Previo Justificativo para el establecimiento del área natural protegida federal p50

(*7)https://www.conanp.gob.mx/anp/consulta/EPJ Wirikuta_ 12oct polign 194 mil csi.pdf Reserva de la Biosfera Wirikuta p30

Figura 8. Geología física de la propuesta de Reserva de la Biosfera Wirikuta

(*8)Velásquez, 1987, págs. 519-520 Tomo III

(*9)Humboldt, 2004, pág. 359

(*10)Ward, 1995,pág. 587 Velásquez, 1987

References

https://desacatos.ciesas.edu.mx/index.php/Desacatos/article/view/2205/1510

"Women Listening to 'The Tree of Rain'" by Kenzaburo Oe, Shinchosha Publishing

https://riudg.udg.mx/bitstream/20.500.12104/73662/1/BCUAAD00047.pdf

https://www.conanp.gob.mx/anp/consulta/EPJ Wirikuta_ 12oct polign 194 mil csi.pdf

https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/americania/article/download/1718/1542/5969

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2012/05/04/espectaculos/a10n1esp

https://desinformemonos.org/nota-wirikuta-fest/

Nierika - una ventana al mundo de los antepasados, Mariana Fresan Jimenez, CONACULTA-FONCA, 2002

documentary movie: “Huicholes - the last peyote guardians” https://vimeo.com/store/ondemand/popup/289830?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fhuicholesfilm.com%2F&ssl=1

You can read up to here for free. The paid part is just one line expressing my gratitude. If you'd like, I'd appreciate it if you could pay for this article, like giving a tip.

ここから先は

この記事が気に入ったらチップで応援してみませんか?