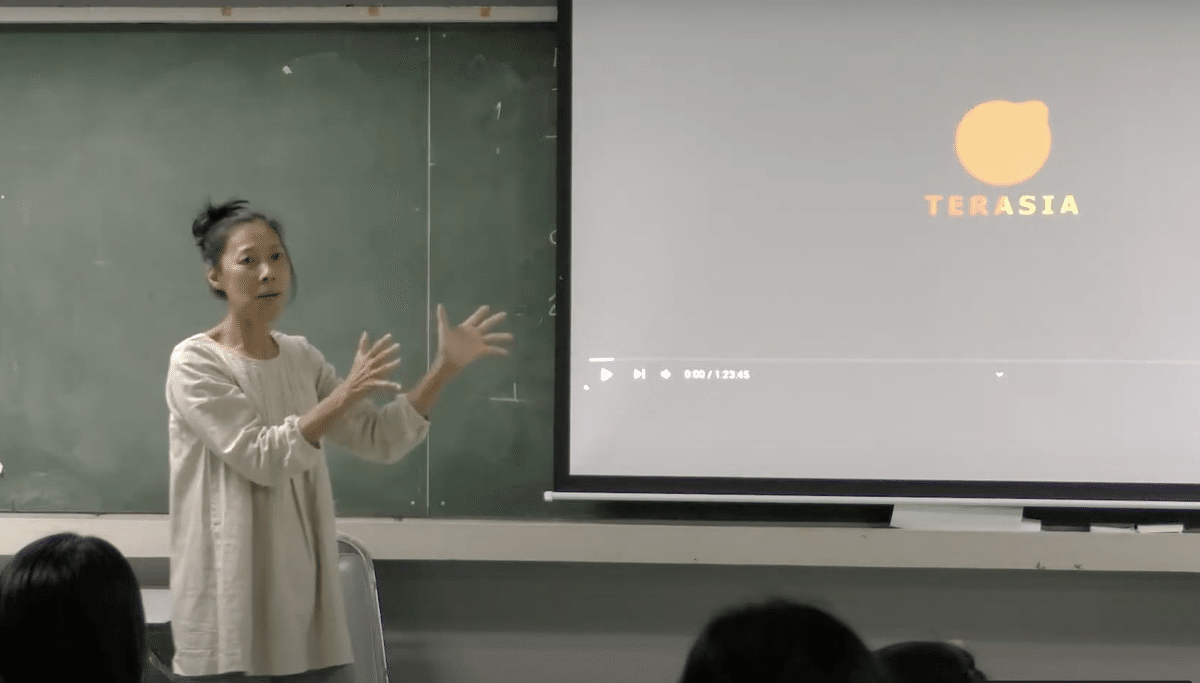

TERASIA Artist Interview Vol. 6: Narumol Thammapruksa (Kop)

Narumol Thammapruksa (a.k.a. Kop) is a key figure in the world of contemporary theatre in Thailand, based in Chiang Mai. Having been part of numerous international projects since the 90s, she is a well-known performance artist worldwide. Yet she never moved to Bangkok or the West; her work has always been rooted in this ancient capital of northern Thailand. We spoke to Kop, who is one of the central members of TERASIA, about her experiences in recent years during the Covid-19 pandemic and her vision for the future.

From Tokyo to Chiang Mai: The Infectious Tera

When we got on the call for this interview, it was early evening in Thailand, and Kop had come straight from invigilating for her students’ exams. She bustles about wearing many hats—alongside her work as a drama teacher at her alma mater, Chiang Mai University, she is not only active as a performing artist and director herself, but also runs a dojo as an aikido master.

TERASIA Online Week 2022 + Onsite

“My life changed completely once I became a full-time faculty member. My students and I create four theatre pieces each year to perform at the university’s theatre. So far, we’ve made over thirty plays of varying scales. Every student has their own context that they draw on in their creative practice, so it’s fascinating. At the moment, my students and I are trying to merge theatre with games. We’re shifting away from the traditional format, in which the audience passively watches the performance, to an immersive, interactive form to make them more absorbed in the play. We’re experimenting with making the audience do more tasks, or something in that direction. We’ve already performed two pieces.”

TERASIA Online Week 2022 + Onsite

For Kop, whose projects had often spanned across various countries, 2020 was a pivotal year. While the Covid-19 pandemic made international travel difficult, and the theatre world was hit hard, she took up her full-time post at the university, and she joined the theatre program, faculty of mass communication as well as the Asia-born performing arts collective, TERASIA. As part of this collective, she put on a performance in Chiang Mai and streamed it online for the first time.

TERA เถระ – Online Viewing and Special Talk Session

What triggered Kop’s involvement with TERASIA was when her friend, Maho Watanabe—the dramaturg of the original Tera created in Japan—got in touch with her to ask about the possibility of performing a remake of Tera in a temple in Thailand once the situation with Covid-19 improved. From the outset, Kop was intrigued by the idea of performing a contemporary theatre piece at a temple.

“I was drawn to this bold idea of putting on a play like that—exploring themes of life and death, and Buddhism—at a temple. I read the script first. There were several layers to the story, and it was rich in nuances, with a refined structure. But I couldn’t imagine how it might be performed. When I saw the recording of the performance, I kept thinking, ‘Ah, so that’s how they did it! That’s what it meant!’ at every turn, and it was so interesting.”

“One problem, though, is that it would be impossible for Japanese artists to put on this play in a temple in Chiang Mai. If anyone tried performing rock music at a Thai temple, they’d get kicked out! In any case, it was difficult to travel from Japan to Thailand because of Covid at the time. So I had the idea of giving it a try with a team in Chiang Mai.”

As Kop and Maho continued their discussion, the play flew off from the original creators to journey to another land, pulled apart and rebuilt into something new, and it spread even more to other people—just like a virus spreading from one person to another, forming variants on different shores. And so, the concept of the “Theatre for Traveling in the Age of Isolation” was born. Around this time, Kop invited other artists, Zun Ei Phyu in Myanmar and Dindon W.S. in Indonesia. All together, they formed the online collective, TERASIA: Theatre for Traveling in the Age of Isolation.

“So that means the first site of ‘infection’ was Chiang Mai. Before long, we began creating a Thai version based on the Japanese play. In Thai, ‘tera’ means ‘priest’—that was a funny coincidence. (In Japanese, ‘tera’ means ‘temple’.) In the Thai version, we carried forward the spirit of the original while transforming it into something totally new. But for people who have seen the original, I’m sure they can tell which elements are reflected in the Thai version.”

In October 2020, TERA เถระ (TERA Tera) was performed at the temple Wat Pha Lat in Doi Suthep-Pui National Park, Chiang Mai, and the streaming was also made available in Japan for a limited time.

“I don’t know where TERASIA will arrive in the very end, but I think it’s very exciting to see artists from different countries creating works sharing the same theme—to watch it evolve and spread to new places.”

Seven Things in Common Between the Japanese and Thai Versions

The Thai version, TERA เถระ (TERA Tera), follows the essence of the original.

The venue is a real temple that is currently in use.

It is a site-specific work. For this play, the play used the authentic surroundings of a temple standing in a national park just as it is, without using props or settings that call to mind things that are not present there.

It includes a live performance of music.

It is not a linear story about views of life and death; rather, it weaves together multiple storylines, going back and forth between them.

The actors play multiple, overlapping parts, switching back and forth between the personae.

It includes scenes in which the audience participates in the play.

It interweaves fact and fiction.

Overcoming Challenges to Perform TERA เถระ (TERA Tera)

In the production of TERA เถระ (TERA Tera), the very first challenge was arranging the venue. In Thailand, it’s not uncommon for temples to be used for various ceremonies accompanied by performances of traditional music, or for local festivals. But when it comes to a contemporary drama performance, there is hardly a precedent.

“The Japanese version is crazy and fun, but I decided to make things calmer for the Thai version. It’s really challenging to put on a play at a Thai temple. Unfortunately, there was an incident in the past at a venerable temple in Chiang Mai, when a live TV show was aired from it with content that misrepresented the history of Buddhism, and after that, the temple became even more conservative. They welcome performances of traditional music and dance, but contemporary theatre is a whole different matter. Since a play has a story, they are wary of it conveying the wrong information and confusing the followers.”

Although their request was declined by a famous temple in Chiang Mai, the team was delighted when the chief priest of Wat Pha Lat was more receptive.

“In Thailand—well, I guess it’s the same anywhere—the outcome depends a lot on who you talk to. This temple is surrounded by a deep forest in the national park. It’s a serene, sacred place, where a clear stream flows across the precincts. We couldn’t have asked for a more ideal venue for a theatre piece that concerns themes like nirvana and the cycle of rebirth. The chief priest liked art—we did invite him to check everything, from the script to the way it’s performed, but he was happy to give us free rein, and we were able to develop the play as we liked.”

“While the temple was generous and lenient, we were still careful when it came to how we presented the play. For example, in our initial plan, there was a scene in which the starring actor, Sonoko Prow, was going to do a handstand with her head on the ground as part of a dance. But someone from the neighborhood, who was watching the rehearsal, said it was preposterous to do a handstand in a temple. So we changed the choreography.”

In recent times, Thailand has been politically unstable. When TERA เถระ (TERA Tera) was performed, someone had to cancel their ticket because they were arrested. Chiang Mai University, where Kop teaches, is located at the foot of the mountain which houses the temple, and anti-government protests were happening on campus.

“There were cases where a student who deals with political themes in their artwork got arrested and couldn’t attend the performance anymore, and a friend of mine canceled their ticket because they had to negotiate the release of a fellow artist. These days it’s not as strict as before, but there’s still some censorship—if your play is critical of the government, you can be under surveillance by soldiers, or the performance can be shut down altogether. It’s been like that for a long time, so we’ve learned to be skillful at avoiding danger. In my view, self-censorship does not mean stopping ourselves from doing something out of fear; instead, it’s all about finding a cleverer way to do something. Under the military-leaning government, it’s necessary to conceal political intentions or allow more breadth of interpretation in the work.”

Kop’s approach is not to attack as her first move, but to observe the other side and thus win the battle—a stance that must have come from her experience as an artist who has survived in the front line for many years. Her flexible mindset has something in common with the spirit of aikido, a martial art that she has pursued so earnestly as to become an instructor and open her own dojo.

Chance Encounters in the Creative Process

By the way, why is the protagonist of TERA เถระ (TERA Tera) Japanese? According to Kop, this was a coincidence, and the decision didn’t have anything to do with the Japanese Tera.

“When I was brainstorming ideas for the new play, I stumbled across a picture book called The Cat Who Went to Heaven in the storeroom at home. The main character is a Japanese artist who is painting a picture of the dying Buddha. Normally, in paintings of the Buddha’s deathbed, there are all kinds of animals, but not a cat. The story is about whether or not the artist will break the taboo and paint his beloved cat in the picture. I decided to use the book’s setting and structure for my play. The cat in the play is based on the calico cat that was actually in the temple.”

“It’s not just for TERA เถระ (TERA Tera)—when I create plays, there’s always an element of chance, and I draw on the different experiences and knowledge of the creative team. For this play, too, I began the process by gathering what the team—the actors, Sonoko and Gig (Kram Thum), and the musicians—had to say about their own views and experiences related to life and death as well as religion. I incorporated their personal stories and what the location offered us, the mountains and rivers around the temple, to make a collage of fiction and non-fiction. That’s my usual method. This approach proved to be a good match with the concept of the Japanese Tera, and I was able to construct a new worldview while also adopting the flow of the original.”

Kop’s style of working with chance occurrences shined in the play’s performance as well. For instance, the venue imparted something special to the play’s atmosphere. The biggest difference between the Thai version and the Japanese Tera is the aura of magnificence that surrounds the whole piece. In large measure, this air of solemnity comes from the environment of the temple, nestled deep in the mountain, standing on a pilgrimage path that priests walk on for spiritual training.

“The audience enters the world of the story by passing between the two statues that stand on either side like gatekeepers. Since the statues are looking at both the present life and the next life, I wanted them to experience the sensation of crossing a threshold into the next life. This idea came from Gig, who played the part of the guide. He was our dramaturg; he has trained as a Buddhist priest in India and Tibet, so he is well versed in this area. As a site-specific work, TERA เถระ (TERA Tera) created a certain atmosphere that was only possible in that place, that moment in time. I’m looking forward to seeing how the work will change when we perform it in a different location.”

2024 will mark the conclusion of one phase of TERASIA’s activities. We are planning an art festival in Indonesia titled, Sua TERASIA, with new performances of Tera by the teams of each country, including Thailand. The performance is set to take place in a unique venue in Bandung called Selasar Sunaryo Art Space.

“For TERA เถระ (TERA Tera), I think it’s possible to perform it as long as we can use both exterior and interior spaces, and we have enough space to move around. Even if we can’t bring in some equipment or there’s no electricity, we can make use of natural lighting and candles, no problem. In Indonesia, we’re planning to perform almost the exact same play as the one we did in Chiang Mai. The language barrier will be tricky, but in the end, I believe everything will go well with theatre magic.”

“There are some things we couldn’t do in our first performance of TERA เถระ (TERA Tera). At first, we were planning to interact with the audience much more. We wanted them to explore the temple, and we had lots of ideas, like an initiation event where the audience looks for things related to death, or projecting a live video of the room on the wall so that they can look at themselves walking out of it. They might have felt like ghosts wandering in the temple—I bet it would’ve been interesting. I’d love to overcome the technical challenges and try out new ways of presentation.”

Embracing the World with an Open Heart

The world is in a highly volatile state, with violence spreading in many places, and tragedies triggered by intolerance of ideas and religions. At the end of our interview, we asked her about her principles: how she has been engaging with the world we live in and disseminating her works.

“The key is not to be obsessed with turning your ideas into something tangible. Try to take things as they come with an open mind, sharpen your five senses and embrace everything you feel. It’s easier said than done—it’s hard to be completely open like that. But through continuous effort to keep your heart wide open, with a flexible mind, you’ll be able to meet new people and new ideas, and discern new paths. For a time you might feel muddled or confused, but it’s not a bad thing to place yourself in chaos. From my experience, as long as I keep myself open, it always leads to some kind of creativity, somehow. I work as if I’m on a journey, going along and staying curious about what chance encounters I’ll have. My creative practice is always like that.”

Photo: Toshiki Yamahata

After the Covid-19 pandemic, we have seen a worldwide decline in large-scale theatrical productions, while more and more small-scale, specific, and personal works have appeared. Kop feels that this trend isn’t necessarily something to lament.

“The amount of funds doesn’t matter when it comes to theatre-making. Even if you don’t have funds, even if it’s small-scale or low-tech, you can express yourself in powerful ways. The experimental, interdisciplinary projects that TERASIA has been doing are a good example of that. If more people started doing activities like this in all kinds of styles across many regions, the range of our expression would expand by a great deal. From a public health standpoint, it’s not good to cram people into a theatre, right? Well then, theatre can evolve at will, free from the constraints of the theatre space.”

“How about coming to Chiang Mai first? It’s fun to visit temples, and you can hike in the mountains, too; it’s culturally unique and complex, so as soon as TERASIA members get a feel for the atmosphere here, I’m sure things are going to get interesting.”

As an artist and an educator, Kop is also committed to social activism. Her spacious home—which includes her aikido dojo, a guest house, and even a small theatre—is like an art village, where local children and students flock together, and sometimes artists even come to stay from both in and outside the country. Though she seems like a Chiang Mai native, she was actually born in Bangkok, and she moved to Chiang Mai when she fell in love with the place in high school. What discoveries await us in Chiang Mai? Now that physical traveling is possible again, why not visit the city as part of a pilgrimage to explore the origins of TERA เถระ (TERA Tera)?

Narumol Thammapruksa (Kop)

Performer, director, producer. Based in Chiang Mai, Narumol Thammapruksa uses theatre as a tool to engage in social activism. In 1997, she established the International WOW Company with performance artists from Indonesia, the US , Taiwan, and India, among other places. She has worked as the art director or the coordinator for a wide range of art events, including World Artist for Tibet, Arts Against War, and the Mekong Project of the New York Dance Theater. As a performer, she has acted in Akaoni (The Red Demon), written and directed by Hideki Noda, first performed at Theatre Tram in 1997; Hotel Grand Asia, an Asian contemporary theatre collaboration performed in 2005; Mobile, produced by the Necessary Stage and performed at Theatre Tram in 2007; and Nioi: The Blind and the Dog, directed by Atsuto Suzuki in 2014. She is also an instructor for the dramatic arts program in the Faculty of Mass Communication at Chiang Mai University.

Mariko Motokawa

A freelance writer since the 90s, Mariko Motokawa has contributed articles to nation-wide magazines and interview articles to both printed and online media. She has also written scripts for radio programs. Her hobbies include singing and theatre.

Yui Kajita

Yui Kajita is a translator, illustrator, and literary scholar, currently based in Germany. She completed her PhD in English Literature at the University of Cambridge. Shortlisted for the 5th JLPP International Translation Competition and longlisted for the John Dryden Translation Competition, she translates prose fiction, poetry, children’s books, folktales, and texts on art. Her publications include "Walter de la Mare: Critical Appraisals" (co-edited, 2022).

https://yuikajita.com

Related Article

いいなと思ったら応援しよう!