Instagram and Self-presentation

When I open my Instagram, my profile shows photos of me traveling, going out, and smiling with friends. I spend a lot of time and effort to maintain this presentation to be excellent. That is because I use Instagram to introduce who I am. However, I hear people say “Instagram does not represent reality.” In other words, there is a difference between how we want others to see ourselves and how we actually perceive others’ presentations on Instagram. This gap makes me wonder why we tend to doubt self-presentation on Instagram to be "real."

Hence, by taking this opportunity, I would like to examine the connections between Instagram and self-presentation. In what follows, I will observe my daily usage of Instagram and investigate how I present myself online. In doing so, this blog will be focusing on the following four aspects: 1) How do I network through Instagram? 2) How does peer surveillance pressure me to show an idealised self? 3) How do I utilise my real and fake accounts?, and 4) How has my personal network shaped my perception of the #blacklivesmatter movement and how has it affected my self-presentation? Additionally, I will discuss how effective Instagram is for “impression management” (Goffman 1959) and why we tend to see “fake identity” on Instagram.

Sociality and Networked Individualism

My regular day starts with checking Instagram. I see several “stories” and like posts that my friends, relatives, and favourite celebrities have uploaded and reply to some messages. I use Instagram to interact with people from different social groups, such as high school classmates and family in Japan and international friends I met in Melbourne. Using Instagram allows me to keep in touch with my old schoolmates, stay connected with family in Japan, and arrange meetups with my friends in Melbourne.

This online behaviour is unique to networked individualism, where individuals are connected through a “sparsely-knit” network (Rainie & Wellman 2012, p125). Rainie and Wellman (2012, p125) explain that the development of social media has contributed to the construction of person-to-person connections by enabling us to reach out to people around communities in which we are engaged or interested. In addition, Rainie and Wellman (2012, p127) suggest that the more online connections we have, the more we are engaged in offline activities.

Source: Author's dataset

For instance, this week, some of my friends I have not seen for a while messaged me, and we caught up for lunch. As Rainie and Wellman (2012, p127) state, we are connected to traditional networks, which we have already built, through social media, which results in participation in social involvements in real life. Thus, Instagram has contributed to my sociality by offering the opportunity to keep up with what all of my peers are doing.

Idealised Self and Internet Surveillance

However, following different social groups makes me concerned about what content to upload on Instagram. Yau and Reich (2018, p197) reveal that Instagram users feel viewed and evaluated by others. This phenomenon is referred to as "internet surveillance" (Lee & Cook 2014, p674). In the internet surveillance, “direct gaze” (Lee & Cook 2014, p679) is replaced by “an imaginary audience” (Yau & Reich 2018, p197) whose existence can be seen through reactions such as “likes” and “viewers” (Yau & Reich 2018, p198). This imaginary audience makes individuals aware of shared norms and socio-cultural expectations (Yau & Reich 2018, p197), which leads to impression management concerns (Kang & Wei 2020, p67).

Source: Author's dataset

This week, I posted this photo of me wearing a black dress at a home party. Conforming to Perloff (2014, p371), female social media users have a high amount of pressure to follow the peer's beauty standards, such as makeup, body shape, and fashion. Uploading this photo shows that I did not want my followers to see myself with bed hair in order to meet socio-cultural standards.

Fears of Wrong Impression and Context Collapse

Peer-surveillance, which I feel on Instagram, has resulted in utilising two accounts, “Rinsta” (real Instagram account) and “Finsta” (fake Instagram account). “Finsta” is an “unofficial” account where people follow a limited number of friends with whom they regularly interact online (Kang & Wei 2020, p67).

Source: Author's dataset (Rinsta and Finsta)

Kang and Wei (2020, p67) suggest that the motivation for creating fake accounts is to avoid the “context collapse” (Boyd 2007) and impression management concerns. As Boyd (2007) argues, the existence of diverse social groups in one space cause “context collapse.” He explains that, since our ideal identities might differ in each social community, it would be hard to present a singular identity on social media (Hogan 2010, p383). Conforming to Kang and Wei (2020, p66), we tend to have a conservative persona to avoid making the wrong impression on “Rinsta.” They also insist that it is hard to express our real identity on the main account because we want to post conservative or sophisticated pictures which satisfy our diverse audiences (Kang & Wei 2020, p67). On the other hand, “Finsta” allows us for flexible ways of expressing ourselves because it is likely to have a small number of people who are close to us (Kang & Wei 2020, p58). In other words, we can portray our non-idealised selves on “Finsta” due to the lack of impression management concerns (Kang & Wei 2020, p67).

Source: Author's dataset

This is a photo from the same party, which I posted on my “Finsta” (fake Instagram account) this week. Sharing this photo on my fake account instead of my real one indicates that I wanted to keep my best self-presentation on “Rinsta” to avoid giving the wrong impression.

Affective Publics and Impression Management

Despite the "context collapse," the existence of diverse groups offers us great opportunities to join social movements. For example, the Black Lives Matter movement has drawn my attention since the story of George Floyd's death in police custody went viral last year. Since then, I have participated in the #blacklivesmatter movement by seeing and uploading pictures on my main account, where I interact with different social groups.

As Crowder (2021, p4) states, Instagram has been a central platform to organize the Black Lives Matter protests (both online and offline) for activists, organizers, and participants, using hashtags and images.

Source: Author's dataset

For example, if I put #blacklivesmatter in search, millions of posts and supporter accounts pop up. Instagram has been used to amplify the voice and visibility of Black Lives (Crowder 2021, p4).

This phenomenon changed my perceptions of the issues for Black Lives and my online engagements. One day, black pictures with the hashtag #blackouttuesday , which my friends posted, filled my newsfeed. I saw some of my friends express how they have been concerned about their "blackness," which made me think about how I can support the movement. According to Van Haperen, Uitermark, and Van der Zeeuw (2020, p310), the nature of Instagram, which allows individuals to share personal experiences through individual networks, has contributed to the development of the movement, gathering the experiences of people worldwide. In addition, Papacharissi (2016, p310) points out that online activities “connect disorganised crowds” and form a sense of community through shared emotions.

Source: Author's dataset

This black picture, which I posted (and could also find on my friends’ profiles), shows that I sensed and internalised the shared mood as well as wanted to be a part of the imaginary community for Black Lives Matter.

However, my engagement in the Black Lives Matter movement happened only temporally. Although I was actively engaged in the movement by sharing posts with hashtags when I saw others post the #blacklivestuesday pictures, I have not uploaded any #blacklivesmatter posts since the black picture. That said, I am confirmed as an “affective public” (Papacharissi 2016, p311), who is mobilized, connected, and identified through emotional attachments with social movements. Papacharissi (2016, p311) suggests that affective publics show spontaneous response, which helps the movement gain high publicity although their participation is not guaranteed for a long time.

The affective action can also be included in impression management. When the #blacklivesmatter posts occupied my newsfeed, I received a sense of community, which encouraged me to create the post to present myself as a supporter. This feeling of community represents the existence of an “imaginary audience” (Yau & Reich 2018, p197), which impacts our conceptions of who we are and how we would like others to see ourselves to meet socio-cultural expectations (Papacharissi 2016, p311). Thus, having the #blacklivesmatter post on my “Rinsta," where I interact with different social groups, has contributed to impression management activities.

Findings

Over the week, I have been observing my Instagram usage and found out that I used Instagram to stay connected with my different social groups, post photos on both “Rinsta” and “Finsta," and be engaged in the #blacklivesmatter movement. In addition, findings indicate that I am a network individual who strategically manages my self-presentation to satisfy my and my peer's socio-cultural expectations by using my real and fake accounts. Thus, in the remaining section, I will discuss how effective Instagram is for “impression management” (Goffman 1959) and why we tend to see “fake identity” on Instagram.

Fake Self or Real Self?

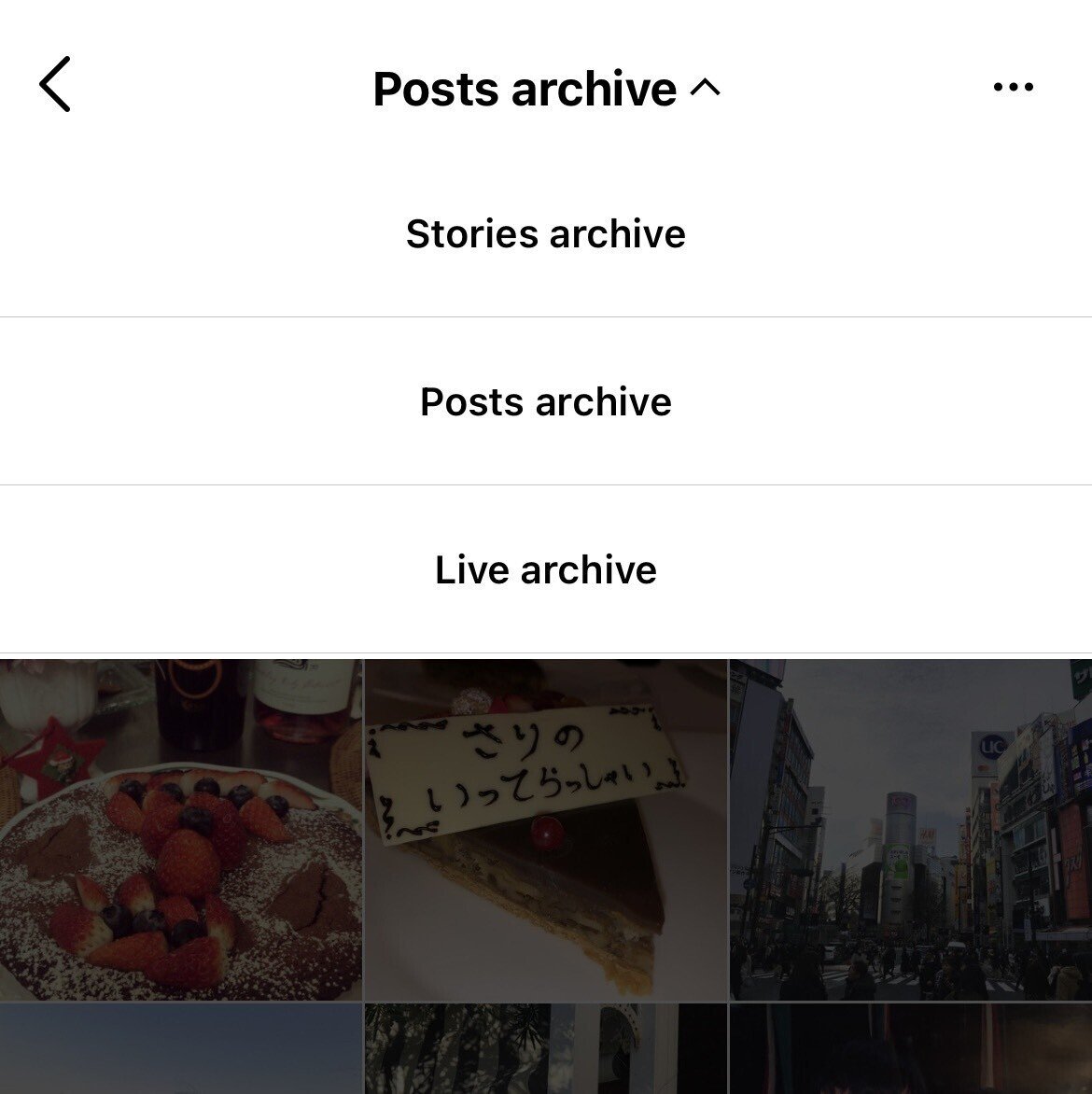

The concept of “Impression management” was coined by Goffman (1959), explaining “how an individual presents an ‘idealized’ rather than the authentic version of herself” (Hogan 2010, p378). As Hogan (2010, p378) states, Impression management can also be seen on social media. As observed, I uploaded only the best and funny photos of me with makeup and a nice outfit even though I had 50 more photos of me wearing the same clothes. In other words, I only chose photos that I want others to see and exhibited them to represent myself on Instagram. This selective behaviour indicates that Instagram allows us flexible ways to gain positive impressions by offering exhibition sites. Conforming to Hogan (2010, p378), we strategically disclose personal details to present an idealised identity online. In addition, Instagram also allows me extra time to reduce the amount of information by enabling "archive." Hogan (2010, p377) suggests that social media also has “curators” (built-in functions) that select what contents to post and where to place them.

Source: Author's dataset

For example, if I do not like photos, I can always hide them from my profile using the "archive" function. As a result, I spend more time on designing the whole presentation of my profile as I want it to be in order to satisfy aesthetic values. Thus, Instagram has it in itself to help us only show a positive presentation of ourselves.

Given that, one of the possible reasons behind the recognition of “fake identity” on Instagram is because we tend to portray ourselves in an idealised or conservative manner to meet norms and socio-cultural expectations or avoid false impressions. Although some might say that we would have the same impression concerns for in-person interactions, I conclude by suggesting that the “exhibitional” aspect of Instagram could emphasise how we strategically present ourselves in a positive way, which results in the perception of “fake identity.”

References

Boyd, d 2007, ‘Why Youth (heart) Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life’, in D Buckingham (eds), Youth, Identity, and Digital Media, MIT Press, Cambridge, pp. 119-142.

Crowder, C 2021, ‘When #BlackLivesMatter at the Women’s March: A Study of the Emotional Influence of Racial Appeals on Instagram’, Politics, Groups, and Identities, vol.10, no.1, pp.1-19.

Goffman, E 1959, ‘The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life’, Anchor Books, New York.

Hogan, B 2010, ‘The Presentation of Self in the Age of Social Media: Distinguishing Performances and Exhibitions Online’, Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol.30, no.6, pp.377-386.

Kang, J & Wei, L 2020, ‘Let Me Be at My Funniest: Instagram Users’ Motivations for Using Finsta (a.k.a., fake Instagram)’, The Social Science Journal, vol.57, no.1, pp.58-71.

Lee, A & Cook, P 2014, ‘The Conditions of Exposure and Immediacy: Internet Surveillance and Generation Y’, Journal of Sociology, vol.51, no.3, pp.674-688.

Papacharissi, Z 2016, ‘Affective Publics and Structures of Storytelling: Sentiment, Events and Mediality’, Information, Communication & Society, vol.19, no.3, pp.307-324.

Perloff, R 2014, ‘Social Media Effects on Young Women’s Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research’, Sex Roles, vol.71, no.11-12, pp.363-377.

Rainie, L & Wellman, B 2012, ‘Networked Relationships’ in L Rainie & B Wellman (eds), Networked: The New Social Operating System, MIT Press, Boston, pp.117-146.

Van Haperen, S, Uitermark, J & Van der Zeeuw, A 2020, ‘Mediated Interaction Rituals: A Geography of Everyday Life and Contention in Black Lives Matter*’, Mobilization: An International Quarterly, vol.25, no.3, pp.295-313.

Yau, J & Reich, S 2018, ‘It’s Just a Lot of Work”: Adolescents’ Self-Presentation Norms and Practices on Facebook and Instagram’, Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol.29, no.1, pp.196-209.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?