Language I: Introduction to Vowel Phonetics Using Ancient Greek

This is part 1 of a series I plan on updating. It will examine aspects of language such as phonetics, grammar and orthography using ancient languages, which are mysterious and fun to reconstruct. If you would like to support my work, please follow me on Twitter at @paganus6.

Most of you who have interacted with me on my Twitter probably are aware that I am quite learned in the field of language. This is likely a result of my prolonged scholarly habits, especially in the fields of archaeology and religious studies. It is only natural that my love of ancient scholarship extends to a love of ancient languages themselves. Indeed, experts in ancient languages are often very valuable men sought after by archaeologists for field research.

I: What is Phonetics?

Today I would like to introduce to you the study of phonetics. Phonetics is simply the way language sounds. It is different from the study of sound itself, which is called acoustics, although there is significant overlap between the two fields as one gets into the "biological underpinnings" of phonetics, i.e. how the sound is produced by the vocal chords, position of the tongue, etc.. It is distinguished from the study of orthography, which is the way language is written. The study of phonetics is referred to as phonology. The phonology of a language is typically a systematic categorization of a language's phonemes, or individual units of sound. Today, you can find the phonology of almost any language on Wikipedia. There is even a dedicated category on Wikipedia which lists the phonology of almost every spoken language you can think of.

As you can imagine, scholars have always been occupied with the question of phonetics, because language is not always written in the same way it is spoken. Virtually every language has orthographic divergence from its phonetics, of which English is a wonderful example. Typically slight phonetic differences by region comprise the basis of most accents, and thus phonetics is very important in the study of dialectology.

Today there is a standard written system called IPA, or the International Phonetic Alphabet, which assigns a distinct notation for each recognizable phoneme in human language. Many of the symbols are part of the standard Latin alphabet, but others were invented or taken from other languages. IPA symbols are typically enclosed in /slashes/ or [square brackets]. The difference is explained better in the appropriate section of the Wikipedia article for IPA than I can manage in the scope of this article.

II: What are Vowels?

Now that I have introduced you to the essentials of phonology, we will move on to the main subject of this article, that being vowels. To put it simply, a vowel is a phoneme produced by the vocal chords without any stricture, or disruption causing friction in the air flow. This is what separates a vowel from a consonant.

Vowels are typically distinguished from each other based on four factors: length, height, backness and roundedness. In languages like French, there is also frequent nasalization.

II.1: Vowel Length

Vowel length is how long the vowel sound is sustained, i.e. how long air keeps flowing out of the mouth/nose and the vocal chords keep vibrating.

Different languages have different ways of notating vowel length. Some languages don't use any. English doesn't have a standard way of notating vowel length, though some combinations of letters almost always stand for a certain long vowel: for example, "ee" almost always represents a long /i/ sound. In IPA, a long vowel has a colon-like next to it. A long /i/ is thus represented by /iː/.

Another common way of representing a long vowel is using a macron. (And no, I am not referring to the French president!) The macron is a straight bar placed over a letter, such as "ā." In most languages, a macron is not actually used as part of day-to-day writing, but is used in dictionaries and pronunciation guides as an indicator of a long vowel. In the field of ancient languages, they are common in modern renditions of written Latin, and in romanized Sanskrit.

II.2: Vowel Height

Vowel height typically refers to how close the tongue is to the roof of the mouth, though it can depend on how open your jaw is too. There are different levels of height, the typical three being close, mid, and open, but there are close-mid and other in-between heights as well, which are actually quite common.

Close vowels have the tongue as close to the roof as possible without creating stricture. Examples are the "ee" (IPA: /iː/) in English "see" and the "ü" (IPA: /yː/) in German "über."

Close-mid vowels can only be defined as being in between a close vowel and a mid vowel. Examples are the IPA sound /eː/, which is the "ay" in English "may," and /øː/, which is the "ö" in German "schön." Interestingly enough, the IPA symbol /ø/ is the actual letter for the sound in standard Danish and Norwegian.

Mid vowels are, again, hard to define. They are typically defined as being midway in between a close vowel and an open vowel. True mid vowels are rarer to find examples for, but the sound of the /ə/ in spoken English is an easy example. It is the "-er" sound in UK English words such as "smaller."

Open-mid vowels are slightly more common. These include the /ɛ/, or the "e" in "bed," and the /ɔ/, or "o" in "not."

The open vowels are quite common, being frequently uttered even by babies. They are defined as having the tongue placed as far from the roof of the mouth as possible. They include the /a/ and /ɑ/ sounds, such as the "a" in English "hat" and "ah" in "nah" used by many German speakers, respectively.

II.3: Vowel Backness

Vowel backness is another thing which comes intuitively and hard to define. Basically, the back part of the tongue is closer to the roof of the mouth depending on how far "back" the the muscle is. /i/ would be defined as a front vowel, and /a/ as a back vowel. /ɜ/ is midway between, and is thus a central vowel. Precision, such as central-back vowels or central-front vowels, isn't common like with vowel height.

II.4: Vowel Roundedness

Vowel roundedness is probably the easiest attribute of vowels to define. Are your lips rounded like when you make an /o/ or /u/ sound? Then the pronunciation is rounded. Otherwise, it's unrounded. That's all there is to it.

II.5: Nasalization

Nasalization is not in Ancient Greek, which is the example language I will give in this article, but it is common in many other languages. It is defined by how much air flow passes through the nose during pronunciation. As far as European languages go, nasal vowels are particularly prevalent in French. They arose when Vulgar Latin transitioned into Old French; I quote Wikipedia:

In the Old French period, vowels become nasalised under the regressive assimilation, as VN > ṼN. In the Middle French period, the realisation of the nasal consonant became variable, as VN > Ṽ(N). As the language evolves into its modern form, the consonant is no longer realised, as ṼN > Ṽ.

That said, nasalization is also apparent in other European languages, such as Polish. They are even used in a Germanic language: the Swedish pseudo-dialect Elfdalian, which some people consider to be a separate language.

III: Diphthongs

I will dedicate this very brief section to a description of diphthongs, as they are better addressed on a per-language basis.

Diphthongs are created when one vowel transitions into another vowel, i.e. when you combine vowels. Diphthongs are very common in almost all languages. The word "eye" is essentially a diphthong of the vowel /a/ and the vowel /ɪ/, forming /aɪ/.

Another word which is useful to know is monophthong, which is a pure, standalone vowel sound. Diphthongization is when a monophthong turns into a diphthong, and monophthongization is when a diphthong turns into a monophthong.

There are triphthongs, which are three combined monophthongs, and so on.

IV: Ancient Greek Vowels

Now that we have a vocabulary built up for describing vowels, let's take a look at Ancient Greek vowel phonology. As with any language, its vowel phonology is largely reflected by its dialect. The typical Ancient Greek dialects are Attic, Ionic, Aeolic, Arcadocypriot and Doric. For this phonology, I will refer to the Classical Attic dialect.

I will begin by splitting the vowels into two groups: a short vowel group and a long vowel group. This is because the vowels used in short form do not necessarily appear in long form, and vice-versa.

IV.1: Short Vowels

Here is a table describing the short vowels used in Classical Attic Greek, courtesy of the Wikipedia article:

As you can see, there are three classes of vowels: close, mid and open. Each of these classes has two subclasses: front and back. And the front class of vowels, has two more sub-subclasses: unrounded and rounded.

IV.1.1: Short Close Vowels

There are three short close vowels: /i/, /y/, and /u/.

/i/ is represented by the Greek letter Iota, or ῐ. It is a short "ee" sound, like the "ea" in American English "eat." It is pronounced at the front, and is unrounded. It is a close front unrounded vowel.

/y/ is represented by the Greek letter Upsilon, or ῠ. There is no English equivalent. It is like a short, quickly spoken version of the "ü" in German "über." It is pronounced at the front like /i/, but is rounded. Just try pronouncing /i/, and then round your lips. You get /y/! It is a close front rounded vowel.

/u/ is also represented by an Upsilon. It is the short version of the English "oo" sound, as in "too." All back vowels in Attic Greek are rounded. /u/ is a close back rounded vowel.

IV.1.2: Short Mid Vowels

There are two short mid vowels in Attic Greek: /e/ and /o/.

/e/ is represented by Greek Epsilon, or ε. It is like a short version of the "ay" in "may." It is a front, unrounded vowel. /e/ is technically a close-mid vowel, but most people don't care and lump it in with the mid vowels anyway. (The Medieval Greek version is /e̞/, which is a true mid vowel!) Its technical name is a close-mid front unrounded vowel.

/o/ is represented by Greek Omicron, or ο. The true /o/ sound is actually not common in English, but is best represented by a short version of the "o" in "Cambodia." Like the other back vowels, /o/ is rounded, and is thus a mid back rounded vowel.

IV.1.3 Short Open Vowels

There is one short open vowel, which is /a/, represented by the Greek letter Alpha, or ᾰ. It is roughly equivalent to the "a" in English "at." It is a front vowel, unrounded, and thus an open front unrounded vowel.

IV.2 Long Vowels

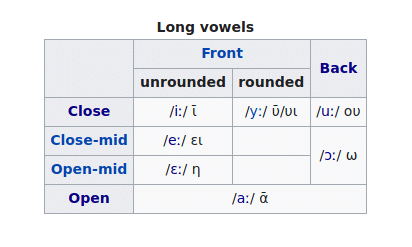

The classes of long vowels are the same as the classes of short vowels.

IV.2.1: Long Close Vowels

The three close long vowels correspond to the short vowels /i/, /y/, and /u/. They are /iː/, /yː/ and /uː/. /iː/ is represented by Iota, while /yː/ can be represented by an Upsilon, or the written digraph υι. (A digraph is a combination of two letters that represent a single sound.)

IV.2.2 Long Mid Vowels

There are three long vowels in Attic Greek which are generally considered to be mid vowels, or are at least lumped into that category. These are /eː/, /ɛː/ and /ɔː/.

/eː/ is the close-mid front unrounded vowel in long form. It is the same is the "ay" in English "may."

/ɛː/ is the long version of the open-mid front unrounded vowel, which doesn't appear in short form. (Don't confuse the IPA with the letter Epsilon!) It is represented by the letter Eta, or η. It is like a long version of the "e" sound in English "bet."

/ɔ:/ is a long version of the open-mid back rounded vowel, which also doesn't appear in short form. It is represented by the Greek letter Omega, or ω. It is equivalent to the "ough" in English "thought".

IV.2.3 Long Open Vowels

Like with the short vowels, there is only one long open vowel, and that is /a:/. It is represented by an Alpha. It is similar to a long version of the "a" in English "hat."

IV.3 Ancient Greek Diphthongs

Ancient Greek once had many more diphthongs than it does now, due to monophthongization undergone in the Hellenistic Period, when true Ancient Greek underwent the process of transforming into Koine Greek. They are divided into two classes: diphthongs that start with a short first vowel, and diphthongs that start with a long first vowel.

All second vowels in Ancient Greek diphthongs are either an /i/ or an /u/.

IV.3.1 Short Vowel Diphthongs

Here is the table for the short vowel diphthongs:

The diphthongs with asterisks before them were later monophthongized.

The close vowel /y/ has a diphthong /yi/, represented by the Greek υι.

The mid vowel /e/ has diphthongs /ei/ (Greek ει) and /eu/ (Greek ευ), and /o/ has /oi/ (Greek οι) and /ou/ (Greek ου).

The open vowel /a/ has /ai/ (Greek αι) and /au/ (Greek αυ).

IV.3.2 Long Vowel Diphthongs

Here is the table for long vowel diphthongs:

The close vowel /ɛː/ has diphthongs /ɛːi/ (Greek ῃ) and /ɛːu/ (Greek ηυ), and /ɔ:/ has diphthongs /ɔ:i/ (Greek ῳ) and /ɔ:u/ (Greek ωυ). "ῃ" and "ῳ" both have Iota subscripts, which are tiny Iotas underneath the letter that imply the letter is followed by an Iota. They ceased being pronounced in later Greek.

There are no long mid vowels with diphthongs in Ancient Greek.

The open vowel /a:/ has two diphthongs: /a:i/ (Greek ᾳ) and /a:u/ (Greek αυ).

V: Conclusion

As you can see, vowels can be quite complicated once we delve into the nitty-gritty details of them. I hope you learned something. In further articles I may go through the phonetics of consonants and phonologies of other languages, such as various stages of Latin.

Have a good day.

Paganus