日米外交アカデミー事前資料読み込み

はじめに

日米外交アカデミーで使う事前資料の要約を生成AIで出力しただけのものです。内容が誤っている可能性が多分にあるので、これを参考にして、配布された原典にあたってください。

Prof.Doi配布 "Snyder_1984_The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics"

はい、添付されたPDFの内容を階層化し、英語と日本語で要約いたします。

英語による要約:

I. The Security Dilemma Concept

The security dilemma refers to the self-defeating aspect of seeking security in an anarchic system

States accumulate power for defense, but this can be misperceived as aggressive by others, leading to a vicious cycle

The security dilemma can operate in armament, adversary, and alliance "games" or interactions

II. Alliance Formation in a Multipolar System: The Primary Alliance Dilemma

In forming alliances, states face a "prisoner's dilemma" incentive structure

They are compelled to ally to avoid the worst outcome of isolation, even though all-around abstention would be better

Specific alignments are shaped by states' particular conflicts and affinities of interest

III. The Secondary Alliance Dilemma After Alignments Form

Allies face risks of abandonment (defection by the ally) and entrapment (being dragged into the ally's conflicts)

Strategies to reduce one risk tend to increase the other, creating a dilemma

Alliance and adversary interactions occur simultaneously, creating linked effects that also shape strategy choices

IV. The Restraining Allies Dilemma and the Straddle Strategy

When allies' partners face off in a crisis, the allies may collaborate to restrain both or support their own partner

In July 1914, Britain faced a severe dilemma and chose an unsuccessful "straddle" strategy of partial support and partial restraint

V. The Alliance Security Dilemma in a Bipolar System

In bipolarity, the risk of abandonment is low, so the dilemma is less severe

Allies are freer to choose divergent strategies toward the adversary with less concern for alliance impacts

The current NATO crisis reflects disagreements over how to manage relations with the adversary, not risk of alliance collapse

VI. The Nuclear Dimension

For Europe, nuclear abandonment means loss of credible U.S. deterrence, entrapment means nuclear war-fighting on its soil

INF deployment presents this dilemma acutely, seen as both deterrence insurance and entrapment risk

VII. Conclusion

The alliance dilemma is more severe in multipolarity than bipolarity

In multipolarity, abandonment fears foster policy convergence; in bipolarity, policy can diverge without threatening alliance cohesion

日本語による要約:

I. 安全保障のジレンマの概念

安全保障のジレンマとは、無政府状態のシステムで安全保障を追求することの自己敗北的な側面を指す

国家は防衛のために力を蓄積するが、これは他国に攻撃的と誤認され、悪循環につながる可能性がある

安全保障のジレンマは、軍備、敵対国、同盟の「ゲーム」や相互作用の中で作用する

II. 多極システムにおける同盟形成:第一次同盟のジレンマ

同盟を形成する際、国家は「囚人のジレンマ」のインセンティブ構造に直面する

全員が棄権した方が良いのに、孤立という最悪の結果を避けるために同盟を組まざるを得ない

具体的な連携は、国家間の特定の対立や利害の類似性によって形作られる

III. 連携形成後の第二次同盟のジレンマ

同盟国は、見捨てられる(同盟国による離反)リスクと巻き込まれる(同盟国の紛争に引きずり込まれる)リスクに直面する

一方のリスクを減らす戦略は、他方のリスクを増大させる傾向があり、ジレンマを生む

同盟と敵対国の相互作用は同時に起こり、戦略選択を形作る相互連関効果を生む

IV. 同盟国を抑制するジレンマと二股戦略

同盟国のパートナーが危機に直面した時、同盟国は両者を抑制するために協力するか、自国のパートナーを支持するかの選択に迫られる

1914年7月、英国は深刻なジレンマに直面し、部分的支持と部分的抑制の失敗に終わった「二股」戦略を選択した

V. 二極システムにおける同盟の安全保障のジレンマ

二極では、見捨てられるリスクが低いため、ジレンマはそれほど深刻ではない

同盟国は、同盟への影響をあまり気にせず、敵対国に対して異なる戦略を選択する自由がある

現在のNATOの危機は、同盟の崩壊のリスクではなく、敵対国との関係をどう管理するかをめぐる意見の不一致を反映している

VI. 核の側面

ヨーロッパにとって、核の放棄とは米国の抑止力の信頼性喪失を意味し、巻き込まれるとは自国の土地で核戦争が行われることを意味する

INF配備は、抑止力の保険とも巻き込まれるリスクとも見なされ、このジレンマを先鋭化させる

VII. 結論

同盟のジレンマは、多極の方が二極よりも深刻である

多極では、見捨てられる恐怖が政策の収斂を促進する。二極では、政策は同盟の結束を脅かすことなく分岐できる

Prof. Doi配布 "Morrow_2000_Alliances"

英語による要約:

I. Introduction

Alliances are neither necessary nor sufficient for effective intervention in wars, raising the question of why states formalize some relations into alliances

II. Decisions to intervene in war

Three key considerations: 1) marginal effect on outcome, 2) individual gains from intervention, 3) potential losses if intervention fails

These considerations help understand arguments about alliance credibility

III. Making alliances credible

A. Signaling

Alliances can signal shared interests if forming them imposes costs that only committed states will bear

Policy coordination and military specialization can impose such costs

B. CommitmentAlliances can create credible commitments by improving allies' ability to fight together or by imposing audience costs for failing to honor the alliance

IV. Neorealism and balance of power

Problems with neorealist view of security as a pure public good and of states as either status quo or revisionist powers

Side payments and diversity of state interests mitigate free-riding problems in balancing against threats

V. Other issues in alliance politics

Tradeoffs between arms and allies in security policy

Burden-sharing within alliances

Managing the risks of abandonment and entrapment in alliances

Differences between symmetric and asymmetric alliances

Domestic political influences on alliance commitments

VI. Future research directions

More detailed models of signaling, commitment, and entrapment in alliances

Empirical studies guided by refined theory

Linking domestic political institutions to alliance behavior

日本語による要約:

I. はじめに

同盟は戦争への効果的な介入に必要不可欠でも十分でもないため、なぜ国家は一部の関係を同盟として形式化するのかという疑問が生じる

II. 戦争への介入の決定

3つの主要な考慮事項:1)結果への限界的影響、2)介入からの個別の利得、3)介入が失敗した場合の潜在的損失

これらの考慮事項は、同盟の信頼性に関する議論を理解するのに役立つ

III. 同盟を信頼できるものにする

A. シグナリング

同盟の形成にコストを課すことで、コミットしている国家のみが負担するシグナルとなり、共有された利害を示せる

政策調整と軍事専門化がそのようなコストを課す可能性がある

B. コミットメント同盟は、同盟国の共同戦闘能力を向上させたり、同盟を守らなかった場合のオーディエンス・コストを課すことで、信頼できるコミットメントを生み出せる

IV. ネオリアリズムとバランス・オブ・パワー

安全保障を純粋な公共財とみなし、国家を現状維持勢力か修正主義勢力かに二分するネオリアリズムの見方の問題点

脅威に対抗する際の「ただ乗り」問題は、サイドペイメントと国家利益の多様性によって緩和される

V. 同盟政治におけるその他の問題

安全保障政策における軍備と同盟のトレードオフ

同盟内の負担分担

同盟における見捨てられることと巻き込まれることのリスク管理

対称的同盟と非対称的同盟の違い

同盟コミットメントに対する国内政治の影響

VI. 今後の研究の方向性

同盟におけるシグナリング、コミットメント、巻き込まれることのより詳細なモデル化

洗練された理論に導かれた実証研究

国内政治制度と同盟行動の関連付け

Prof. Doi配布 "Kenwick_McManus_2021_Deterrence Theory and Alliance Politics"

English:

Deterrent Effect of Alliances

1.1 Bargaining Model ApproachAlliances may shift the bargaining range

Potential to contribute to deterrence by reducing information asymmetries

1.2 Alliance Reliability and CredibilityDistinction between actual likelihood of intervention (reliability) and perceived likelihood (credibility)

Enhancing credibility through hand-tying mechanisms and sunk costs

Causes of Deterrence Failure

2.1 Changes in the Distribution of Power and Interests

2.2 Moral Hazard Problem

2.3 Security DilemmaEmpirical Record on Alliances and War

Variation in effects across different eras

Differences based on alliance types

Impact of time since alliance formation

Influence of strategic environment

Variation based on level of hostility

Recent Trends in the International Alliance System

Shift towards defensive alliances

Stagnation of the alliance system

Rise of New Signaling Mechanisms

Defense cooperation agreements

Leadership visits and other signals

Japanese:

同盟の抑止効果

1.1 交渉モデルアプローチ同盟は交渉の幅を変える可能性がある

情報の非対称性を減らすことで抑止に貢献する可能性

1.2 同盟の信頼性と信憑性実際の介入可能性(信頼性)と認識された介入可能性(信憑性)の区別

手を縛るメカニズムや埋没コストによる信憑性の向上

抑止失敗の原因

2.1 力と利益の分布の変化

2.2 モラルハザード問題

2.3 安全保障のジレンマ同盟と戦争に関する実証的記録

時代による効果の違い

同盟の種類による違い

同盟形成からの時間経過の影響

戦略環境の影響

敵対レベルによる違い

国際同盟システムの最近の傾向

防衛同盟への移行

同盟システムの停滞

新たなシグナリングメカニズムの台頭

防衛協力協定

首脳訪問など

Here is a hierarchical summary of the "Deterrence Theory and Alliance Politics" chapter in both Japanese and English:

Japanese:

同盟の抑止効果

1.1 交渉モデルアプローチ同盟は交渉の幅を変える可能性がある

情報の非対称性を減らすことで抑止に貢献する可能性

1.2 同盟の信頼性と信憑性実際の介入可能性(信頼性)と認識された介入可能性(信憑性)の区別

手を縛るメカニズムや埋没コストによる信憑性の向上

抑止失敗の原因

2.1 力と利益の分布の変化

2.2 モラルハザード問題

2.3 安全保障のジレンマ同盟と戦争に関する実証的記録

時代による効果の違い

同盟の種類による違い

同盟形成からの時間経過の影響

戦略環境の影響

敵対レベルによる違い

国際同盟システムの最近の傾向

防衛同盟への移行

同盟システムの停滞

新たなシグナリングメカニズムの台頭

防衛協力協定

首脳訪問など

English:

Deterrent Effect of Alliances

1.1 Bargaining Model ApproachAlliances may shift the bargaining range

Potential to contribute to deterrence by reducing information asymmetries

1.2 Alliance Reliability and CredibilityDistinction between actual likelihood of intervention (reliability) and perceived likelihood (credibility)

Enhancing credibility through hand-tying mechanisms and sunk costs

Causes of Deterrence Failure

2.1 Changes in the Distribution of Power and Interests

2.2 Moral Hazard Problem

2.3 Security DilemmaEmpirical Record on Alliances and War

Variation in effects across different eras

Differences based on alliance types

Impact of time since alliance formation

Influence of strategic environment

Variation based on level of hostility

Recent Trends in the International Alliance System

Shift towards defensive alliances

Stagnation of the alliance system

Rise of New Signaling Mechanisms

Defense cooperation agreements

Leadership visits and other signals

Prof. Kohama配布 "Hedley Bull on Diplomacy (from the Anarchic Society)"

Diplomacy and International Order

Introduction

In Chapter 7 of "The Anarchical Society," Hedley Bull explores the concept of diplomacy and its role in maintaining international order. He addresses three primary questions:

What is diplomacy?

How does diplomacy contribute to international order?

What is the relevance of diplomacy to international order at present?

Definitions of Diplomacy

Bull identifies three important senses of the term "diplomacy":

General Conduct: The conduct of relations between states and other entities with standing in world politics by official agents and peaceful means. This broad definition encompasses all official and peaceful interactions.

Professional Diplomacy: Relations conducted specifically by professional diplomats, such as ambassadors and envoys. This is a more traditional and narrower view.

Tactful Conduct: Relations carried out in a manner that is tactful or subtle, emphasizing the skillful handling of international affairs.

He prefers the first, broad definition, emphasizing that diplomacy involves official agents conducting peaceful relations on behalf of states or recognized political entities.

Functions of Diplomacy

Bull outlines several key functions that diplomacy fulfills in relation to international order:

Communication: Facilitating communication between political leaders of states and other actors in world politics. Diplomats serve as messengers, ensuring accurate and effective transmission of information.

Negotiation: Negotiating agreements between states. Diplomats identify overlapping interests and work towards mutually beneficial solutions.

Information Gathering: Collecting and assessing information about foreign countries to inform policy decisions. This includes understanding political climates, intentions, and capabilities.

Minimization of Friction: Reducing tensions and misunderstandings between states through tactful communication and adherence to conventions. Diplomats help manage conflicts and prevent escalation.

Symbolic Representation: Symbolizing the existence of an international society and mutual recognition among states. Diplomats embody the idea of international cooperation and shared norms.

The Present Relevance of Diplomacy

Bull discusses changes in the role and perception of diplomacy in the contemporary world:

Decline of the Resident Ambassador: The traditional role of resident ambassadors has diminished due to direct communication between leaders, technological advancements, and the proliferation of special missions and agencies.

Rise of Multilateral Diplomacy: There's been a shift from bilateral diplomacy to multilateral diplomacy through international organizations and conferences, reflecting the interconnectedness of global issues.

Shift from Negotiation to Political Warfare: In periods of low consensus or high tension, states may resort to confrontational tactics rather than traditional negotiation, emphasizing propaganda or "diplomacy by insult."

International Technical Management: In areas where states perceive their interests as identical, technical experts may collaborate directly, reducing the need for traditional diplomatic negotiation.

Despite these changes, Bull argues that diplomacy remains central to maintaining international order. The essential functions of diplomacy—such as communication, negotiation, information gathering, minimizing friction, and symbolic representation—continue to be vital. While the methods and actors involved in diplomacy may have evolved, the underlying necessity for diplomatic engagement persists.

外交と国際秩序

はじめに

ヘドリー・ブルの『アナーキカル・ソサエティ』第7章では、外交の概念とそれが国際秩序の維持に果たす役割が探求されています。彼は以下の3つの主要な質問に取り組んでいます。

外交とは何か?

外交は国際秩序にどのように貢献するのか?

現在の国際秩序における外交の関連性は何か?

外交の定義

ブルは「外交」という用語の3つの重要な意味を特定しています。

一般的な関係:国家や世界政治で地位を持つ他の主体が、公式の代理人を通じて平和的手段で関係を行うこと。これはすべての公式で平和的な相互作用を包含する広い定義です。

職業的な外交:大使や使節など、専門の外交官によって行われる関係。これはより伝統的で狭義の見方です。

巧みな関係:丁寧で微妙な方法で行われる関係。国際問題の巧妙な処理に重点を置いています。

彼は最初の広い定義を支持し、外交が国家や認められた政治的存在の公式代理人によって平和的に行われる関係であることを強調しています。

外交の機能

ブルは、外交が国際秩序に関連して果たすいくつかの主要な機能を挙げています。

コミュニケーション:国家や他の世界のアクターの政治指導者間のコミュニケーションを促進する。外交官はメッセンジャーとして働き、情報の正確で効果的な伝達を保証します。

交渉:国家間の合意を交渉する。外交官は重なり合う利益を見つけ、相互に有益な解決策に向けて努力します。

情報収集:政策決定を支えるために、外国に関する情報を収集・評価する。政治的な気候、意図、能力を理解することが含まれます。

摩擦の最小化:丁寧なコミュニケーションと慣習の遵守を通じて、国家間の緊張や誤解を減らす。外交官は紛争を管理し、エスカレーションを防ぎます。

象徴的な役割:国際社会の存在と国家間の相互認識を象徴する。外交官は国際協力と共有される規範の理念を体現します。

現在の外交の関連性

ブルは、現代世界における外交の役割と認識の変化について論じています。

駐在大使の役割の低下:指導者間の直接的なコミュニケーション、技術の進歩、特別な任務や機関の増加により、伝統的な駐在大使の役割は減少しました。

多国間外交の台頭:国際機関や会議を通じて、二国間外交から多国間外交へのシフトが起こっています。これはグローバルな問題の相互関係性を反映しています。

交渉から政治的闘争への移行:コンセンサスが低い時期や緊張が高まる時期には、国家は伝統的な交渉よりも対立的な戦術に頼ることがあり、プロパガンダや「侮辱外交」を強調します。

国際的な技術的管理:国家が自国の利益を同一視する分野では、技術専門家が直接協力し、伝統的な外交交渉の必要性を減らしています。

これらの変化にもかかわらず、ブルは外交が国際秩序の維持において依然として中心的な役割を果たしていると主張しています。外交の本質的な機能であるコミュニケーション、交渉、情報収集、摩擦の最小化、そして象徴的な役割は、方法や関与するアクターが進化しても引き続き重要です。

Prof. Kohama配布 "Frieden Lake Schultz World Politics Ch2"

Summary (English):

Interests, Interactions, and Institutions in World Politics:

Interests: These are the goals that actors pursue through their actions in international relations. States seek security, power, wealth, or ideological goals, while non-state actors may prioritize profit, environmental concerns, or human rights.

Interactions: These occur when the choices of two or more actors combine to produce political outcomes. Cooperation and bargaining are the two primary types of interactions. Cooperation occurs when actors work together for mutual benefit, while bargaining involves the distribution of a fixed resource.

Institutions: Institutions create the rules of the game, shaping interactions and facilitating cooperation. Domestic and international institutions set standards of behavior, verify compliance, and reduce the costs of joint decision-making. Institutions are often biased, reflecting the power dynamics present when they were created.

Actors and Their Interests:

States, political leaders, bureaucracies, firms, international organizations, and NGOs all play a role in shaping international relations. Each has its own specific goals, such as wealth, influence, or policy objectives. These goals shape the interactions between different actors.

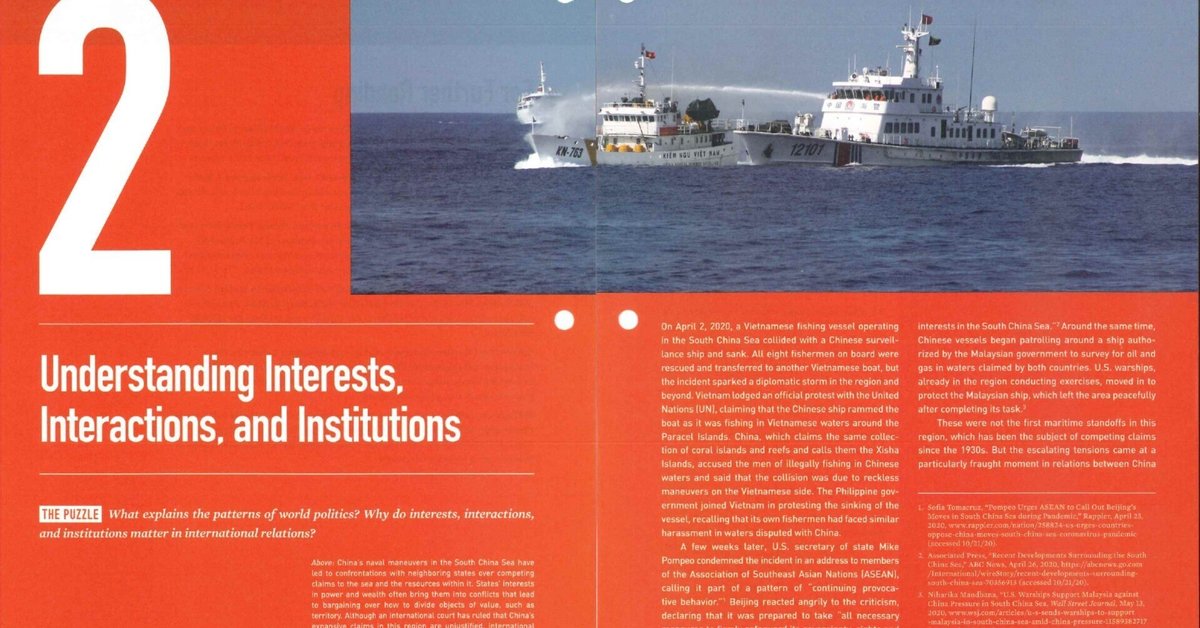

Example: The South China Sea dispute involves states (China, Vietnam, and others) seeking territorial control and security, while external powers like the U.S. have an interest in maintaining regional stability and trade routes.

Forms of Interaction:

Cooperation: When actors work together to achieve shared goals, as seen in alliances or trade agreements.

Bargaining: When actors must divide a fixed resource, such as territory or market access. For example, in trade negotiations, countries negotiate to secure favorable terms.

Strategic Interaction: Actors anticipate how others will react to their choices. For example, Vietnam's response to China in the South China Sea depends on its expectation of U.S. support.

Challenges to Cooperation:

Coordination Problems: Occur when actors agree on the need to cooperate but face difficulty aligning their actions, like deciding which side of the road to drive on.

Collaboration Problems: Arise when actors have incentives to cheat or defect, even when cooperation is beneficial. The classic example is the Prisoner’s Dilemma, where both parties have an incentive to betray the other.

Bargaining Power:

Power in Bargaining: The ability of one actor to impose costs on another or to withstand the consequences of no deal. Power shapes outcomes, often reflecting military or economic capabilities.

Coercion: Threatening or imposing costs to force another actor to make concessions. For instance, tariffs in trade disputes or military force in territorial disputes.

Institutions and Their Role:

Setting Standards of Behavior: Institutions set clear rules that reduce ambiguity, helping actors understand their obligations and monitor compliance.

Verifying Compliance: Institutions provide mechanisms like inspections (e.g., IAEA monitoring nuclear programs) to verify compliance with agreements.

Reducing Decision-Making Costs: Institutions help streamline collective decision-making, reducing the costs of coordinating actions across multiple actors. The UN and ASEAN are examples of institutions that facilitate political and economic cooperation.

Institutions and Power Dynamics:

Policy Bias: Institutions are shaped by the power dynamics present at their creation. For example, the UN Security Council’s veto power for the five permanent members reflects the outcome of post-WWII negotiations.

Institutional Change: As global power dynamics shift, institutions may evolve, as seen with China's increasing influence in the IMF or the creation of alternative institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Compliance with Institutions:

Why Follow the Rules?: States comply with institutions because the benefits of cooperation often outweigh the costs of rule violations. For example, the U.S. complies with WTO rulings to maintain the overall benefits of the global trading system.

Enforcement Challenges: International institutions lack enforcement mechanisms and rely on self-policing. Dispute resolution mechanisms like arbitration panels provide legitimacy to claims but cannot force states to comply.

Conclusion:

Complexity in International Relations: International politics is shaped by a combination of interests, interactions, and institutions. While cooperation is possible, it is often limited by power dynamics, competing interests, and the difficulty of enforcement. Institutions facilitate cooperation but cannot compel it, particularly in conflicts involving major powers like the U.S. and China.

要約 (日本語):

国際政治における利害、相互作用、制度:

利害: アクターが国際関係において追求する目標。国家は安全保障、権力、富、またはイデオロギー的目標を追求し、非国家アクターは利益、環境問題、人権などを優先する。

相互作用: 2つ以上のアクターの選択が政治的結果を生む際に発生する。相互作用には協力と交渉があり、協力はアクターが共通の利益を達成するために協力するもので、交渉は固定されたリソースの分配に関わる。

制度: 制度はゲームのルールを作り、相互作用を形作り、協力を促進する。国内および国際的な制度は行動の基準を設定し、遵守を確認し、共同意思決定のコストを削減する。

アクターとその利害:

国家、政治指導者、官僚機構、企業、国際機関、NGOなどが国際関係を形成する。それぞれが富、影響力、政策目標などの具体的な目標を持ち、これがアクター間の相互作用を形作る。

例: 南シナ海の紛争は、領土と安全保障を求める国家(中国、ベトナムなど)と、地域の安定と貿易ルート維持に関心を持つ米国などが関与する。

相互作用の形態:

協力: アクターが共通の目標を達成するために協力する場合、例えば同盟や貿易協定で見られる。

交渉: アクターが固定されたリソース(領土や市場アクセス)を分け合う必要がある場合。貿易交渉では、各国が有利な条件を得ようとする。

戦略的相互作用: アクターは他者の選択を予測して行動する。例えば、ベトナムが米国の支援を期待して中国にどう対応するか決定する場合。

協力への課題:

調整問題: アクターが協力の必要性に同意しても、行動を調整するのが困難な場合。道路交通ルールの例がある。

協力問題: アクターが協力しても裏切るインセンティブがある場合。囚人のジレンマの例では、両者が裏切る動機を持っているため、協力が難しくなる。

交渉力:

交渉における力: 他者にコストを課す能力や、合意に至らない結果に耐える能力が結果を左右する。軍事力や経済力が影響を与える。

強制: 関税や軍事力を用いて相手に譲歩を強いる戦略が含まれる。

制度の役割:

行動基準の設定: 制度は明確なルールを設定し、アクターが義務を理解し、遵守を監視できるようにする。

遵守の確認: IAEAの核施設検査のように、遵守を確認する仕組みを提供する。

意思決定コストの削減: 制度は多くのアクター間での協力を容易にし、UNやASEANが政治的、経済的協力を促進している。

制度と権力の力学:

政策バイアス: 制度は作成時の権力力学を反映している。例えば、国連安保理の拒否権は第二次世界大戦後の結果を反映している。

制度の変化: 世界の権力力学が変化するにつれて、制度も変化する。IMFでの中国の影響力の増加やAIIBの創設が例である。

制度に従う理由:

なぜルールを守るのか: 協力がもたらす利益が大きいため、アクターは制度に従うことが多い。WTOのルールに従う理由は、国際貿易制度の利益を享受するためである。

強制の課題: 国際制度は強制メカニズムを欠き、自己監視に依存している。仲裁委員会などの紛争解決メカニズムは合法性を提供するが、遵守を強制することはできない。

結論:

国際政治の複雑性: 国際政治は利害、相互作用、制度の組み合わせによって形作られる。協力は可能だが、権力力学や競合する利害、強制の難しさが制約となる。制度は協力を促進するが、必ずしもそれを強制することはできない。

Prof. Vllasi配布 "USDOS_How PRC Seeks to Reshape the Global Information Environment"

英語による要約:

I. Executive Summary

The PRC spends billions annually on foreign information manipulation efforts to promote pro-PRC narratives and suppress critical voices.

The PRC's approach involves leveraging propaganda and censorship, promoting digital authoritarianism, exploiting international organizations and bilateral relationships, pairing cooptation and pressure, and exercising control over Chinese-language media.

If unchecked, the PRC's efforts could reshape the global information environment, leading nations to make decisions that subordinate their interests to Beijing's.

II. Introduction

President Xi has significantly expanded PRC efforts to shape the global information environment.

The PRC commands a massive state media ecosystem overseen by the CCP's Central Propaganda Department and United Front Work Department.

Within its borders, the PRC curates an information environment that prevents voices from providing accurate information that could generate pressure on authorities.

III. Element 1: Leveraging Propaganda and Censorship

Beijing seeks to maximize the distribution of pro-PRC content through expanding state media, purchasing foreign media, content-sharing agreements, diplomatic engagement, media partnerships, sponsoring influencers, and misrepresenting commentary.

The PRC censors critical voices globally through manipulative social media tactics, monitoring communications, online and real-world intimidation, and diplomatic pressure.

IV. Element 2: Promoting Digital Authoritarianism

The PRC exports surveillance technologies and information control tactics while advancing authoritarian digital norms.

This enables Beijing to track sentiment, fine-tune censorship, advance an infrastructure for surveillance, and exploit intelligence collection to shape messaging.

V. Element 3: Exploiting International Organizations and Bilateral Relationships

The PRC uses international organizations to amplify its narratives, isolate Taiwan, retroactively alter documents, and promote its digital governance vision.

Bilaterally, Beijing uses summits, agreements, domestic lobbying and legal action to amplify its narratives and suppress critical voices.

VI. Element 4: Pairing Cooptation and Pressure

The PRC coopt political elites, subnational groups, and journalists to shape their views in line with its narratives.

Beijing pressures corporations and individuals that challenge its narratives through threats of regulatory action, visa denial, and transnational repression.

VII. Element 5: Exercising Control Over Chinese-Language Media

The PRC shapes overseas Chinese-language content by furnishing low-cost content, leveraging fora, and exploiting WeChat.

In parallel, Beijing suppresses criticism through financial pressure, censorship via WeChat, and harassment of content producers.

VIII. Conclusion

The PRC's information manipulation degrades the integrity of the global information environment.

If successful, Beijing's efforts would diminish freedom to express critical views and bend fora and relationships to amplify its narratives.

日本語による要約:

I. エグゼクティブサマリー

中国は毎年数十億ドルを外国の情報操作に費やし、中国寄りのナラティブを促進し、批判的な声を抑圧している。

中国のアプローチは、プロパガンダと検閲の活用、デジタル権威主義の促進、国際機関と二国間関係の悪用、懐柔と圧力のペアリング、中国語メディアに対する統制の行使を含む。

もし抑止されなければ、中国の努力は世界の情報環境を再構築し、国家に中国の利益に従属する決定をさせる可能性がある。

II. イントロダクション

習近平国家主席は、世界の情報環境を形作るための中国の取り組みを大幅に拡大した。

中国は、中国共産党の中央宣伝部と統一戦線工作部が監督する巨大な国営メディアのエコシステムを有している。

国内では、中国は当局への圧力を生み出す可能性のある正確な情報を提供する声を防ぐ情報環境を管理している。

III. 要素1:プロパガンダと検閲の活用

北京は、国営メディアの拡大、外国メディアの購入、コンテンツ共有契約、外交的関与、メディアパートナーシップ、インフルエンサーのスポンサー、論評の不当表示を通じて、中国寄りのコンテンツの配信を最大化しようとしている。

中国は、世界中の批判的な声を、操作的なソーシャルメディアの戦術、通信の監視、オンラインと実世界の脅迫、外交的圧力を通じて検閲している。

IV. 要素2:デジタル権威主義の促進

中国は、権威主義的なデジタル規範を推進しながら、監視技術と情報統制の戦術を輸出している。

これにより、北京は感情を追跡し、検閲を微調整し、監視のためのインフラを推進し、メッセージを形成するために諜報収集を悪用することができる。

V. 要素3:国際機関と二国間関係の悪用

中国は、自国のナラティブを増幅し、台湾を孤立させ、文書を遡及的に改変し、デジタルガバナンスのビジョンを促進するために、国際機関を利用している。

二国間では、北京は首脳会議、協定、国内ロビー活動、法的措置を利用して、自国のナラティブを増幅し、批判的な声を抑圧している。

VI. 要素4:懐柔と圧力のペアリング

中国は、政治的エリート、国家以下の集団、ジャーナリストを懐柔して、自国のナラティブに沿って彼らの見解を形成している。

北京は、自国のナラティブに挑戦する企業や個人に、規制措置、ビザ拒否、国境を越えた弾圧の脅威を通じて圧力をかけている。

VII. 要素5:中国語メディアに対する統制の行使

中国は、低コストのコンテンツを提供し、フォーラムを活用し、WeChatを悪用することで、海外の中国語コンテンツを形成している。

並行して、北京は、財政的圧力、WeChatを介した検閲、コンテンツ制作者への嫌がらせを通じて批判を抑圧している。

VIII. 結論

中国の情報操作は、世界の情報環境の完全性を損なっている。

もし成功すれば、北京の努力は批判的な見解を表現する自由を減らし、フォーラムと関係を中国のナラティブを増幅するために屈服させるだろう。

Prof. Vllasi配布 "NIDS_2023_China Cognitive Warfare_Redacted"

英語による要約:

I. Introduction

As China develops into a strong country, it has increasingly challenged the US-centered international order through non-military means like influence operations and maritime gray zone situations.

The report examines how China's military organizational reforms have affected its actions in the psychological/cognitive domains and gray zone, and the organizational structure for implementing them.

II. Chapter 1: Restructuring China's Military Organizations

Xi Jinping's reforms strengthened the CCP's leadership over the military through the CMC chairman responsibility system and Party committees in the military.

The People's Armed Police and China Coast Guard were reorganized to maintain public security in peacetime and contribute to PLA joint operations in contingencies.

Coordination mechanisms were developed between the military and other governmental actors.

III. Chapter 2: China's Increasing Influence Operations

The PLA is increasingly engaged in activities associated with the Party's overall influence operations in the psychological/cognitive domain.

Key PLA activities include the "Three Warfares" of public opinion, psychological, and legal warfare.

Influence operations against Taiwan exemplify the Party's and PLA's wide-ranging activities and threats to Taiwan.

IV. Chapter 3: China's Maritime Gray Zone Situations

To become a "great maritime power," the Xi regime has coordinated the PLA Navy, China Coast Guard, and maritime militia based on military-police-civilian and "five-in-one" joint actions.

It has integrated the coast guard and maritime militia into the military chain of command, expanded outposts, armed the coast guard, and strengthened the militia.

Gray zone operations differ between the East and South China Seas due to varying environments and adversaries.

V. Conclusions

The CCP's leadership is critical to China's external actions. Strengthening it has eased "fragmented authoritarianism" to some extent.

However, coordination remains weak in some domains like influence operations. Maritime cooperation has evolved more.

China's reliance on the CCP for coordination can be a weakness if the Party weakens. Influence operations risk being overrated.

The Russia-Ukraine War may impact Chinese thinking on cognitive domain operations and non-military means. Technological innovation will affect future influence operations and gray zone activities.

日本語による要約:

I. はじめに

中国が強国として発展するにつれ、影響力行使や海上グレーゾーン事態などの非軍事的手段を通じて、米国中心の国際秩序に挑戦してきた。

本レポートでは、中国の軍事組織改革が、心理・認知領域とグレーゾーンでの行動にどのような影響を与えたか、それらを実行するための組織構造を検討する。

II. 第1章:中国の軍事組織再編

習近平の改革は、中央軍事委員会主席責任制と軍内の党委員会を通じて、軍に対する中国共産党の指導力を強化した。

武装警察と中国海警は、平時の治安維持と有事の人民解放軍との共同作戦への貢献のために再編された。

軍と他の政府機関との連携メカニズムが整備された。

III. 第2章:中国の影響力行使の増大

人民解放軍は、心理・認知領域における党全体の影響力行使に関連した活動に、ますます従事するようになっている。

人民解放軍の主要な活動には、世論戦、心理戦、法律戦の「三戦」が含まれる。

対台湾の影響力行使は、党と人民解放軍の広範な活動と台湾への脅威を示す好例である。

IV. 第3章:中国の海上グレーゾーン事態

「海洋強国」となるため、習近平政権は、軍警民の共同行動と「五位一体」に基づき、海軍、海警、海上民兵を統合してきた。

海警と海上民兵を軍の指揮系統に組み込み、拠点を拡大し、海警を武装化し、民兵を強化してきた。

グレーゾーン作戦は、環境と相手国が異なるため、東シナ海と南シナ海では違いがある。

V. 結論

中国共産党の指導力は、中国の対外行動に不可欠である。それを強化することで、「分断された権威主義」をある程度緩和できた。

しかし、影響力行使などの一部の分野では、連携は依然として弱い。海上協力はより進化している。

中国が連携に中国共産党に依存していることは、党が弱体化した場合の弱点となり得る。影響力行使は過大評価のリスクがある。

ロシアのウクライナ侵攻は、認知領域作戦や非軍事的手段に関する中国の考え方に影響を与える可能性がある。技術革新は、将来の影響力行使とグレーゾーン活動に影響を与えるだろう。

Prof. Wiegand配布 "Morganthau Chapter"

I. The Balance of Power as a Universal Concept

A. Definition and usage

"Balance" or "equilibrium" used in many sciences

Applies to systems composed of autonomous forces

B. Two key assumptions

Stability within a system requires balance among elements

Equilibrium is disturbed by outside forces or changes in elements

C. Examples in different fields

Human body: balance among organs

Economics: balance between supply/demand, exports/imports, etc.

Society: balance between regions, industries, classes, etc.

II. Different Methods of the Balance of Power

A. Divide and Rule

Weakening competitors by dividing them

Examples: French policy toward Germany, Soviet policy toward Europe

B. Compensations

Territorial compensations to maintain balance

Examples: Treaty of Utrecht, colonial territory distribution

C. Armaments

Arms races to match or surpass rivals' military power

Disarmament attempts to stabilize balance

D. Alliances

Most important manifestation of balance of power

Nations can increase own power, add others' power, or withhold power from adversaries

E. The "Holder" of the Balance

Can be a third party not permanently aligned with either side

Shifts support to maintain equilibrium

Great Britain as historical example

III. Evaluation of the Balance of Power

A. Unreality of perfect balance

Uncertainty in power calculations

Nations seek superiority rather than equality

Leads to maximum power acquisition for safety margin

B. Consequences

Perpetual fear and competition

Tendency to consolidate temporary advantages

Can lead to diplomatic pressure or war

Here is the same summary in Japanese:

I. 普遍的概念としての勢力均衡

A. 定義と用法

多くの科学分野で「バランス」や「均衡」が使用される

自律的な力で構成されるシステムに適用

B. 2つの重要な前提

システム内の安定には要素間のバランスが必要

均衡は外部の力や要素の変化によって乱される

C. 様々な分野での例

人体:器官間のバランス

経済:需要/供給、輸出/輸入などのバランス

社会:地域、産業、階級間のバランスなど

II. 勢力均衡の様々な方法

A. 分割統治

競争相手を分割して弱体化させる

例:ドイツに対するフランスの政策、ヨーロッパに対するソ連の政策

B. 補償

バランス維持のための領土的補償

例:ユトレヒト条約、植民地領土の分配

C. 軍備

ライバルの軍事力に匹敵または凌駕するための軍拡競争

バランス安定化のための軍縮の試み

D. 同盟

勢力均衡の最も重要な現れ

国家は自国の力を増強、他国の力を追加、または敵対者から力を奪うことができる

E. 「均衡保持者」

どちらの側にも恒久的に同盟しない第三者となりうる

均衡維持のために支持を変える

歴史的例としてのイギリス

III. 勢力均衡の評価

A. 完全なバランスの非現実性

力の計算における不確実性

国家は平等ではなく優位性を追求

安全マージンのための最大限の力の獲得につながる

B. 結果

永続的な恐怖と競争

一時的な優位性を固定化する傾向

外交的圧力や戦争につながる可能性

Prof. Wiegand配布 "Mearsheimer Ch 2"

I. Introduction

States seek to maximize power and achieve hegemony

This chapter presents the logic behind why states pursue power

II. Why States Pursue Power

A. Five assumptions about the international system:

The international system is anarchic

Great powers inherently possess offensive military capability

States can never be certain about other states' intentions

Survival is the primary goal of great powers

Great powers are rational actors

B. These assumptions lead to three behavioral patterns:

Fear

Self-help

Power maximization

C. States aim to be the hegemon in the system

Survival would be almost guaranteed as hegemon

States look for opportunities to gain power at others' expense

D. Calculated aggression

States consider the balance of power before taking offensive action

They weigh costs and risks against potential benefits

III. Hegemony's Limits

A. Definition of hegemony

Domination of the entire system

Can be global or regional

B. Difficulty of achieving global hegemony

Virtually impossible except with clear nuclear superiority

The "stopping power of water" limits power projection

C. Regional hegemony

The best outcome a great power can realistically hope for

The United States is the only regional hegemon in modern history

D. Behavior of regional hegemons

Seek to prevent peers in other regions

Prefer at least two great powers in other regions

Act as "offshore balancers"

IV. Power and Fear

A. Relationship between power and fear

More powerful states generate more fear among rivals

Level of fear affects intensity of security competition

B. Types of power

Potential power: population size and wealth

Actual power: military forces, especially land power

C. Factors affecting fear levels:

Presence of nuclear weapons

Geographic barriers (e.g., large bodies of water)

Distribution of power in the system

D. Focus on capabilities over intentions

Intentions are ultimately unknowable

States balance against capabilities

V. Hierarchy of State Goals

A. Survival as the primary goal

B. Non-security goals (e.g., economic prosperity, ideology, unification)

C. Pursuit of non-security goals allowed if not conflicting with security

D. Security trumps other goals when conflicts arise

VI. Creating World Order

A. Great powers do not cooperate purely for world order

B. International order as a by-product of self-interested behavior

C. Challenges to creating world order:

Disagreement on how to achieve stability

Inability to ignore power considerations

VII. Cooperation Among States

A. Factors inhibiting cooperation:

Concerns about relative gains

Fear of cheating

B. Types of cooperation:

Alliances against common enemies

Ganging up on third states

Arms control agreements

C. Limitations of cooperation

Takes place in a fundamentally competitive world

Cannot eliminate security competition

VIII. Conclusion

Structure of international system causes great powers to seek hegemony

Survival as principal motive, but anarchy encourages aggressive behavior

Theory treats all states alike, differing only in amount of power controlled

Here is the same hierarchical summary in Japanese:

I. はじめに

国家は力を最大化し、覇権を達成しようとする

この章では、国家が力を追求する理由の背後にある論理を提示する

II. 国家が力を追求する理由

A. 国際システムに関する5つの前提:

国際システムは無政府状態である

大国は本質的に攻撃的な軍事能力を持つ

国家は他国の意図を確実に知ることはできない

生存が大国の主要な目標である

大国は合理的な行動主体である

B. これらの前提は3つの行動パターンにつながる:

恐怖

自助

力の最大化

C. 国家はシステムにおける覇者になることを目指す

覇者として生存がほぼ保証される

国家は他国を犠牲にして力を得る機会を探す

D. 計算された侵略

国家は攻撃的行動を取る前に力のバランスを考慮する

コストとリスクを潜在的な利益と比較検討する

III. 覇権の限界

A. 覇権の定義

システム全体の支配

グローバルまたは地域的な覇権がありうる

B. グローバル覇権達成の困難さ

明確な核優位がない限り、事実上不可能

「水の阻止力」が力の投射を制限する

C. 地域的覇権

大国が現実的に望める最良の結果

アメリカは近代史上唯一の地域的覇者

D. 地域的覇者の行動

他の地域にライバルが生まれるのを防ごうとする

他の地域に少なくとも2つの大国が存在することを好む

「オフショア・バランサー」として行動する

IV. 力と恐怖

A. 力と恐怖の関係

より強力な国家はライバル国の間でより多くの恐怖を生み出す

恐怖のレベルが安全保障競争の激しさに影響する

B. 力の種類

潜在的な力:人口規模と富

実際の力:軍事力、特に陸軍

C. 恐怖のレベルに影響を与える要因:

核兵器の存在

地理的障壁(例:大きな水域)

システム内の力の分布

D. 意図よりも能力に焦点を当てる

意図は究極的に知ることができない

国家は能力に対してバランスを取る

V. 国家目標の階層

A. 生存が主要な目標

B. 非安全保障目標(例:経済的繁栄、イデオロギー、統一)

C. 安全保障と矛盾しない限り非安全保障目標の追求が許容される

D. 衝突が生じた場合、安全保障が他の目標に優先する

VI. 世界秩序の創造

A. 大国は純粋に世界秩序のためには協力しない

B. 国際秩序は自己利益的行動の副産物

C. 世界秩序創造の課題:

安定性の達成方法に関する意見の不一致

力の考慮を無視することの不可能性

VII. 国家間の協力

A. 協力を阻害する要因:

相対的利益に関する懸念

裏切りの恐れ

B. 協力の種類:

共通の敵に対する同盟

第三国に対する共同行動

軍備管理協定

C. 協力の限界

根本的に競争的な世界で行われる

安全保障競争を排除することはできない

VIII. 結論

国際システムの構造が大国に覇権を求めさせる

生存が主要な動機だが、無政府状態が攻撃的行動を促す

理論はすべての国家を同様に扱い、違いは力の量のみ

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?