Tymoigne & Wray 『MMT批判に答える』の抜粋訳と、これを作成した理由

こんにちは、望月慎(望月夜)@motidukinoyoruと申します。

(blog「批判的頭脳」、togetter、noteマガジン一覧)

(拙著『図解入門ビジネス 最新 MMT[現代貨幣理論]がよくわかる本』(秀和システム)(2020/3/24 発売))

ティモワーニュとレイによるMMT批判への再反論論文が書かれたのは2013年のこと、今から8年も昔の話になる。

基本的にこの論文は、アメリカにおける非主流派/異端派、特にポスト・ケインジアンによるMMT批判に応える内容となっていて、一般のMMT論争とはややテイストが異なるが、MMTを理解する入門としては有用である……という認識であった。

といっても、私自身もwankonyankoricky氏による翻訳(Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6)を通じて最初に知ったもので、論争のまとめとして読むというより、MMTのポイントを理解するガイドとして利用したというのが実際のところである。

ところが、日本の非主流派/異端派経済学者界隈では、まさにこの論文での再反論先となったような、周回遅れのMMT批判が精力的に輸入される事態が最近散見されるようになった。

Epstein, Gerald著 徳永潤二、内藤敦之、小倉将志郎訳 『MMTは何が間違いなのか?: 進歩主義的なマクロ経済政策の可能性』, 東洋経済新報社

3/21(日)武蔵大学国際シンポジューム『現代貨幣理論(Modern Monetary Theory) の批判的検討』

こうした動きに対しては、ヘッドホン氏によるエプシュタイン本批判や、私自身によるエプシュタイン批判、また徳永論文への批判など、散発的な形で批判を加えてきた。

しかしながら今回、恥ずかしながらようやくTymoigne & Wray (2013) の存在を思い出し、上述のような日本の状況を踏まえ、論文の中でも論争上重要であるだろう部分を抜粋訳してみせた次第である。

私個人にとっては、取り上げた部分は、(当然ながら)目新しいポイントではなく、以前からMMTerらが継続的に主張し、また我々が紹介してきた論点である。

問題は、8年ものラグがあるにも関わらず、こうした再反論を踏まえない形でMMT批判が展開されようとしている日本の非主流派/異端派経済学界隈の惨状にあり、かような悲劇的状況にあっては、このような『退屈な』文献紹介にも意味があると考えた次第である。

(*著作権は当然ながら論文著者に帰属し、このnoteによる金銭的利益は一切発生していない)

*各引用部分には、その内容に応じたサブタイトルをつけているが、これは私自身が整理のためにつけた独自のものであり、元論文著者とは直接的には関係しない。

MMT批判のカテゴライズ……貨幣の起源、政府通貨における租税の役割、財政政策、金融政策、発展途上国への妥当性、政策提言の妥当性

pp.3

Critiques of MMT can be classified according to five categories: views about origins of money and the role of taxes in the acceptance of government currency, views about fiscal policy, views about monetary policy, the relevance of MMT conclusions for developing economies, and the validity of the policy recommendations of MMT.

拙訳:

MMTに対する批判は、「貨幣の起源と政府通貨の受け入れにおける租税の役割に関する見解」、「財政政策に関する見解」、「金融政策に関する見解」、「MMTの結論の発展途上国への妥当性」、「MMTの政策提言の妥当性」の5つのカテゴリーに分類される。

①租税と統合政府仮説、②国内民間部門と財政政策・財政収支の適切なスタンス、③中央銀行、財務省、国内経済の間の相互作用、④海外部門、為替レート体制と財政政策への影響、国の発展レベル、⑤MMTの政策的枠組みと結論

pp.3

This article addresses each of these categories using the circuit approach and national accounting identities, and by progressively adding additional economic sectors. The first section focuses on the government sector. The section shows the importance of taxes for the smooth working of a government-based monetary system, and starts to deal with the consolidation hypothesis. The second section focuses on the domestic private economy and draws some conclusions about the conduct of fiscal policy and the proper stance of the government fiscal balance. The third section adds the central bank and studies the interactions among the central bank, the Treasury and the domestic economy. The fourth section adds the foreign sector and studies the impact on fiscal policy, the role of exchange-rate regimes as well as the level of development of a country. The fifth section focuses on the policy framework and conclusions of MMT.

拙訳:

本稿では、サーキット・アプローチと国民会計関数を用いて、段階的に経済部門を追加しながら、これらのカテゴリーをそれぞれ取り上げている。最初のセクションでは、政府部門に焦点を当てる。当該セクションでは、政府ベースの通貨システムが円滑に機能するためには租税が重要であることを示し、統合政府仮説の処理を開始する。第2節では、国内の民間経済に焦点を当て、財政政策の実施と政府の財政収支の適切なスタンスについて、いくつかの結論を導き出す。第3節では、中央銀行を加え、中央銀行、財務省、国内経済の間の相互作用を研究する。第4章では、海外部門を追加し、財政政策への影響、為替レート体制の役割、国の発展レベルを研究する。第5章では、MMTの政策的枠組みと結論に焦点を当てる。

通貨の負債性と課税

pp.6-7

A central means to give value to a financial instrument is through the necessity of its issuer to take back that financial instrument in the future.6 Households promise to take back their mortgage notes (when they repay their mortgages), businesses promise to take back their bonds (repaying principal due when bonds mature). When your neighbor returns to you your “cup of sugar” IOU, you must accept it and provide the sugar or another mutually acceptable payment. The same applies to government monetary instruments: the currency issuer must promise to accept the currency in payments to itself. Households meet that reflux requirement by working and earning a monetary wage, companies do it by making a monetary profit, government does it by taxing (broadly speaking—other types of payments to authorities can also be important, such as fees, fines, tithes, and tribute). Each of these means creates a demand for the financial instrument of the specific economic unit. The broader the capacity of the domestic private sector to earn monetary earnings, the easier it is to take back its financial instruments, and so the more broadly their financial instruments will be accepted. Generally, the broader the capacity to tax, the broader the demand for the government’s currency.

拙訳:

金融商品に価値を与える方法の中核は、金融商品の発行者がその金融商品を将来的に引き取る不可避性にある6。家計は住宅ローンの手形を引き取る(住宅ローンを返済する)ことを約束し、企業は債券を引き取る(債券が満期になったら元本を返済する)ことを約束する。隣人があなたの「カップシュガー」の借用書を返してきたら、あなたはそれを受け取り、砂糖を提供するか、あるいは相互に受け入れられる別の支払いをしなければならない。政府の通貨も同様で、通貨発行者は自分への支払いにその通貨を受け入れることを約束しなければならない。家計は働いて金銭的な賃金を得ることで、企業は金銭的な利益を上げることで、政府は課税(広義には、手数料、罰金、"十分の一税"、年貢など、当局への他の種類の支払いも重要である)することで、この還流の要件を満たす。これらの手段はそれぞれ、特定の経済単位の金融商品に対する需要を生み出す。国内の民間部門が金銭的な収益を得る能力が高いほど、その金融商品を引き取ることが容易になり、その結果、その金融商品はより広く受け入れられることになる。一般に、課税能力が広ければ広いほど、政府の通貨に対する需要も広くなるのである。

マサチューセッツ湾岸植民地のthe bills of credit通貨

pp.7

Thus, taxes are essential because they help the government currency to circulate at par (thereby making the payment system more efficient) and because they promote price stability by removing some purchasing power from domestic economic units. This lesson was learned rapidly by the Massachusetts Bay colonies--so much so that while residents of the colonies were first skeptical about the value of the bills of credit for economic and political reasons, bills rapidly were used as currency and circulated at par:

When the government first offered these bills to creditors in place of coin, they were received with distrust. […] their circulating value was at first impaired from twenty to thirty per cent. […] Many people being afraid that the government would in half a year be so overturned as to convert their bills of credit altogether into waste paper, […]. When, however, the complete recognition of the bills was effected by the new government and it was realized that no effort was being made to circulate more of them than was required to meet the immediate necessities of the situation, and further, that no attempt was made to postpone the period when they should be called in, they were accepted with confidence by the entire community […] [and] they continued to circulate at par. (Davis 1901, 10, 15, 18, 20)

拙訳:

このように、税金は、政府通貨が額面通りに流通するのを助け(それによって決済システムがより効率的になる)、国内の経済単位から購買力の一部を奪うことで物価の安定を促進するため、必要不可欠なものである。この教訓は、マサチューセッツ湾岸の植民地ではすぐに理解された。植民地の住民は、経済的・政治的理由から信用状の価値に最初は懐疑的であったが、信用状はすぐに通貨として使用され、額面通りに流通するようになった。

『政府が初めて貨幣の代わりに信用状を債権者に提示したとき、信用状は不信感をもって迎えられた。[...] その流通価値は、最初は20%から30%にまで損なわれた。多くの人々は,半年後には政府がひっくり返って,信用状が完全に紙くずになってしまうのではないかと恐れていた。[...] しかし,新政府によって信用状の完全な承認がなされ,当面の必要性を満たすために必要な分以上に流通させようとする努力はなされていないことが理解され,さらに,信用状が償還されるべき時期を先延ばしにしようとする試みもなされていないことがわかると,信用状は社会全体に確信を持って受け入れられ[...],額面通りに流通し続けたのである。(Davis 1901, 10, 15, 18, 20)』

MMTとインフレ、実物的制約と金融的制約、完全雇用orボトルネック、内生的貨幣供給ビューとマネタリズム否定

pp.8-9

We can now address two points that Palley brings forward:

The central policy assertion of MMT is the non-existence of financial constraints on government spending below full employment. The claim is government can issue money to finance non-inflationary spending as long as the economy is below full employment. […] The only time expansionary fiscal policy pays for itself is with balanced budget fiscal policy, but that is ruled out by MMT which denies the need to finance deficits with taxes. In a static economy that means the money supply would keep growing relative to output, causing inflation that would tend to undermine the value of money. (Palley 2013, 14)

First, Palley’s critique that MMT’s “proposed” monetary financing of government spending is inflationary is wrong headed. His point rests on the view that tax and monetary creation are choices within the budget constraint of the Treasury. As we have argued above, “money creation” and taxing are not alternatives but rather come at different points in the financing process. In other words, we are providing a description of the financing process, not a policy recommendation. Palley does not understand the logic of the financing sequence: the “money creation” must occur before the “money” is redeemed in tax payment.

Second, MMT does make a clear difference between real and financial constraints; this is one of the crucial points of MMT. Inflation is a real constraint not a financial constraint, so inflation does not prevent the government from funding itself—as such the capacity of the government to fund itself is independent of the state of the economy. Indeed, as the currencyissuer, government can always outbid the private sector, which certainly is a concern of MMT. At full employment, increasing government spending will be inflationary; before full employment government can cause bottlenecks and inflation of the prices of key inputs. Further, and more surprisingly, Palley seems to adopt a simplistic monetarist view of the cause of inflation when he claims that money supply growth greater than growth of output would “undermine the value of money”. Like most heterodox approaches, MMT rejects the quantity equation explanation of inflation. In our view, inflation would result if the relation between government spending and taxing were wrong, not because the ratio of money supply (however measured) and GDP were wrong. In that, we follow the traditional “endogenous money” view that the ratio of money stock to national output is an uninteresting residual.

拙訳:

ここで、Palley氏が提示した以下の2つのポイントについて説明する。

『MMTの中心的な政策主張は、完全雇用以下における政府支出に財政的制約が存在しないことだ。その主張とは、経済が完全雇用以下である限り、政府はインフレにならない支出のために貨幣を発行できるというものなのである。[...] 拡張的な財政政策が自らを賄うのは、均衡財政政策の場合だけだが、MMTでは赤字を税金で賄う必要性を否定しているため、それは除外されている。静的経済では、貨幣供給量が生産量に対して増加し続けることになり、貨幣の価値を損なう傾向のあるインフレを引き起こすことになる。(Palley 2013, 14) 』

まず、MMTの「提案する」政府支出の貨幣的資金調達がインフレを引き起こすというPalley氏の批判は誤りだ。彼の指摘は、税と貨幣の創造が財務省の予算制約の中での選択であるという見解に基づいている。先に述べたように、「貨幣の創造」と「課税」は代替手段ではなく、資金調達プロセスの異なるポイントで行われるものである。つまり、私たちは資金調達プロセスの説明をしているのであって、政策提言をしているわけではないのだ。Palley氏は、資金調達の順序の論理を理解していない。要するに、「貨幣」が納税で償還される前に「貨幣創造」が行われなければならないのである。

第二に、MMTは実物的制約と金融的制約を明確に区別している。これはMMTの重要なポイントの一つだ。インフレは金融的制約ではなく、実物的制約だ。したがって、インフレは政府の資金調達を妨げるものではない。実際、通貨発行者である政府は、いつでも民間部門を凌駕することができ、これは確かにMMTの関心事項である。完全雇用下では、政府支出を増やすとインフレになるが、完全雇用の前でも、政府がボトルネックを発生させて、重要な投入物の価格でインフレが起きる可能性がある。また、もっと驚くべきことに、Palley氏はインフレの原因について単純なマネタリストの見解を採用しているようで、貨幣供給量の増加が生産高の増加を上回ると「貨幣の価値が損なわれる」と主張している。多くの異端派的アプローチと同様に、MMTはインフレの量的方程式による説明を否定している。我々の考えでは、政府の支出と課税の関係が誤っていればインフレになるのであって、貨幣供給量(測定方法はともかく)とGDPの比率が間違っているからインフレになるのではない。この点では、マネーストックと国民の生産高の比率は大した意味のない残差であるとする伝統的な「内生的貨幣」の考え方に従っている。

十分条件としての租税貨幣論と例外の不在 / 「時間の霧」mists of timeと現代通貨

pp.9-11

Palley, Rochon and Vernengo, find MMT to be extreme in its linking of money and taxes:

Unfortunately, MMT sets up unnecessary controversy by asserting that the obligation to pay taxes is the exclusive reason for the development of money (Palley 2013, 3) Sovereignty, understood as the power to tax and to collect in the token of choice, is not the main explanation for the existence of money, even if modern money is ultimately chartal money. (Rochon and Vernengo 2003, 57)

The word money is used too broadly in these quotes. To be more precise, MMT does argue that imposition by authorities of obligations (including taxes, fines, fees, tithes and tribute) is logically sufficient to “drive” acceptance of the government’s currency. Some who adopt MMT (including us) believe that the historical record, such as it exists, does point to these obligations as the origin of money: government currency was first made acceptable through the imposition of an obligation, and the creation of a monetary unit of account was also initiated by a government to denominate those obligations. Once these were established, government currency was used for other purposes as explained further in section 2. Over time financial instruments issued by others were denominated in the same money unit, and some of these also began to circulate.

But to be clear, MMT does not argue that taxes are necessary to drive a currency or money—critics conflate the logical argument that taxes are sufficient by jumping to the conclusion that MMT believes there can be no other possibility. In truth, MMT is agnostic as it waits for a logical argument or historical evidence in support of the belief of critics that there is an alternative to taxes (and other obligations). We have not seen any plausible alternative. The orthodox-Austrian Robinson Crusoe story is unacceptable as it contains several logical flaws (Gardiner 2004; Ingham 2000; Desan 2013). The other common explanation relies on an infinite regress story: Billy-Bob accepts currency because he thinks Buffy-Sue will accept it (Buchanan 2013). In our view, that is less than satisfying. If Palley, Rochon, or Vernengo has an alternative story, we would love to see it.

More importantly, as Rochon and Vernengo seem to agree, modern “chartal” currency is today “driven” by taxes. In other words, even if the “origins” of money are hidden in the “mists of time”, we can look around the modern world and note that almost without exception each national government adopts its own money of account, imposes tax obligations in that unit, and issues currency as well as central bank reserves also denominated in that unit. In turn, the government accepts (and hence “destroys” in redemption) high powered money (bank reserves) in tax payment. For government currency, it is not an oversimplification to state that taxes play a central role in the origins of today’s monetary systems. It is logical once one moves away from a commodity view of money and into the financial view of money in which the government plays a central role. Private money-denominated IOUs developed for other reasons than the imposition of taxes, but history suggests that government provided the foundation upon which modern monetary systems developed. When new countries are formed (for example, out of the disintegrating Soviet Union), their governments adopt a new money of account, impose tax and other obligations in that unit, issue a new currency in that unit, and accept their own liabilities in tax payment. Whatever might have been the case in prehistoric times, with few exceptions we observe a familiar pattern throughout recorded history.

拙訳:

Palley、Rochon、Vernengoの3人は、MMTが貨幣と税金を結びつける点で極端であると考えているようだ:

『遺憾ながら、MMTは、納税義務が貨幣の発展の唯一の理由であると主張することで、不必要な論争を引き起こしている(Palley 2013, 3)。選択した形で課税し、徴収する力として理解される主権は、たとえ現代の貨幣が究極的には表券貨幣であるとしても、貨幣の存在の主要な説明にはならない。(Rochon and Vernengo 2003, 57)』

こうした引用部では、貨幣という言葉があまりにも広い意味で使われてしまっている。より正確に言えば、MMTは、政府による義務(税金、罰金、手数料、十分の一税、年貢を含む)の賦課が、政府の通貨の受容を「駆動」するのに論理的に十分であると主張しているのである。MMTを採用している人の中には(私たちも含めて)、歴史的な記録によれば、こうした義務が貨幣の起源であると考えている人もいる。すなわち、政府の通貨は義務の賦課によって初めて受け入れられるようになり、その義務を表わす通貨単位の作成も政府によって開始された。これらが確立された後、政府通貨は2項で説明したように他の目的のために使用された。やがて、他人が発行した金融商品も同じ通貨単位で表示されるようになり、それらの一部も流通するようになった。

しかし、念のために言っておくと、MMTは通貨や貨幣を動かすために税金が必要だと主張しているわけではない。批判者は、税金が十分条件であるという論理的な議論を混同して、MMTがそれ以外の可能性はないと考えているという結論に飛びついている。実際には、MMTは不可知論者であり、税金(やその他の義務)に代わるものがあるという批判者の信念を裏付ける論理的な議論や歴史的な証拠を待っている。我々は、これまで尤もらしい代替案を見たことがないが。オーソドックスなオーストリアのロビンソン・クルーソーの話は、いくつかの論理的欠陥を含んでいるため、受け入れられない(Gardiner 2004; Ingham 2000; Desan 2013)。もう一つの一般的な説明は、無限後退の物語に依存している:ビリー・ボブが通貨を受け入れるのは、バフィー・スーが受け入れると思っているからである、と(Buchanan 2013)。我々の考えでは、これは満足できるものではない。Palley、Rochon、Vernengoのいずれかが別のストーリーを持っているのであれば、それを見せていただきたいものである。

さらに重要なことは、RochonとVernengoも同意しているように、現代の「表券」通貨は今日、税金によって「駆動」されているということである。言い換えれば、貨幣の「起源」が「時間の霧」の中に隠されているとしても、現代の世界を見渡せば、ほぼ例外なく、各国政府が独自の勘定科目の貨幣を採用し、その単位で納税義務を課し、その単位で通貨や中央銀行の準備預金を発行していることがわかる。その結果、政府は納税のためにハイパワード・マネー(銀行準備金)を受け入れる(つまり、償還で「破壊」する)。政府通貨については、今日の通貨システムの起源に税金が中心的な役割を果たしていると言っても過言ではないだろう。商品的貨幣観から、政府が中心的な役割を果たす金融的貨幣観に移行するなら、それは論理的なことである。貨幣で単位付けされた民間のIOUは、税金の賦課とは別の理屈で発展したが、歴史的に見れば、政府が現代金融制度の基礎を提供したことになる。崩壊したソビエト連邦から新しい国ができると、その国の政府は新しい貨幣を採用し、その単位で税金などの義務を課し、その単位で新しい通貨を発行し、自らの納税義務を負うことになる。先史時代にはどうであったかは別にして、ごく少数の例外を除いて、記録された歴史の中ではおなじみのパターンが見られる。

(記述ではなく)理論としての統合政府とその妥当性

pp.12-13

Palley, Fiebiger, Gnos, Rochon, and Lavoie complain that this is not descriptive of how fiscal operations work today. The Massachusetts colony experiment does not provide relevant insights about current fiscal operations. The contemporary Treasury is not a bank that can keystroke funds into existence, and it can run out of funds if it does not tax and issue bonds. While the U.S. Treasury can issue its own monetary instruments (coins), it typically does not operate that way and there are institutional and political constraints that prevent the Fed from directly funding the Treasury. Thus, they claim, one should interpret the accounting budgetary equation of the Treasury as a budget constraint with alternative choices. Lavoie argues that the consolidation hypothesis leads proponents of MMT to make counterintuitive and over-the-top logical conclusions that immediately put off new readers, and prevent the contributions of MMT from being accepted more widely:

The government budget restraint shows the accounting relationship whereby governments that issue sovereign money can, in principle, finance spending by printing money. However, that also requires a particular institutional arrangement between the fiscal authority and the central bank. […]. This is an important issue of political economy. MMT dismisses this political economy and assumes there is and should be full consolidation of the fiscal authority and central bank. (Palley 2013, 6)

Wray argues that the Treasury does not need to procure funds in order to spend but creates new funds as it spends such that in ‘theory’ fiscal receipts cannot be spent. This description of fiscal policy could perhaps be applied to monetary systems that existed centuries ago, for example, when the colonial government of Massachusetts issued the first fiat paper currency in America circa 1690. The bills of credit were spent into the economy and redeemable not for a precious metal but for tax liabilities. Does the US Treasury finance its expenses in the modern era in a way comparable to the colonial experiences of the 1690s-1700s? (Fiebiger 2012a, 3) In short there is no utility in depicting the “government” as financing all spending by net/new money creation when that claim applies only to the central bank (Fiebiger 2013, 66)

One problem with the MMT “benign neglect” / “do not worry” analyses of public finances is that the “keystroke” theme is non-descriptive. […] MMT gets fiscal policy back-to-front by supposing that the Treasury expends funds without first procuring funds. The Treasury is not a bank and if it does not collect fiscal receipts it cannot spend because it has no ‘money’ (Fiebiger 2013, 71).

While attempting to convince economists and the public that there are no financial constraints to expansionary fiscal policies (except artificially erected ones), neochartalists end up using arguments that become counter-productive. There is little or nothing to be gained from contending that government can spend by simply crediting a bank account; that the Treasury can act as if it were a bank; that government expenditures must precede tax collection; that the creation of high-powered money requires government deficits in the long run; that central bank advances can be called public spending; or that taxes and issues of securities do not finance government expenditures. This entire list of counter-intuitive claims follows a logic, premised on the consolidation of the government’s financial activities with the central bank’s operations, thereby modifying standard terminology. […] But MMT now brings itself to an end with a theory dependent on the counter-factual consolidation of the government and the central bank. This goes beyond a mere debate of (over-)simplification. The consolidation premise does not describe reality and it twists standard terminology (Lavoie 2013, 23)

拙訳:

Palley、Fiebiger、Gnos、Rochon、Lavoieは、上記が今日の財政運営を記述するものではないと訴えている。”マサチューセッツ植民地での実験は、現在の財政運営についての適切な洞察を提供していない。現代の財務省は、資金をキーストロークで生み出すことができる銀行ではなく、課税したり債券を発行したりしなければ資金が不足してしまう。米国財務省は独自の通貨手段(コイン)を発行することができるが、通常はそのような運用はしておらず、FRBが財務省に直接資金を供給することを妨げる制度的・政治的制約がある。したがって、財務省の会計上の予算方程式は、代替の選択肢がある予算制約として解釈すべきだ”と彼らは主張する。Lavoie氏は、『統合政府仮説は、直観に反する大げさな論理的結論へとMMT支持者を導くものであり、それは直ちに新しい読者を遠ざけ、MMTの貢献がより広く受け入れられることを妨げるものである』と主張している:

『政府予算制約は、ソブリンマネーを発行する政府が、原則として貨幣を印刷することで支出を賄うことができるという会計上の関係を示している。しかし、そのためには、財政当局と中央銀行の間に特定の制度的な取り決めが必要となる。[...]. これは、政治経済学の重要な問題である。MMTはこの政治経済学を否定し、財政当局と中央銀行が完全に統合されていること、またそうすべきであることを前提としている。(Palley 2013, 6) 』

『Wray氏は、財務省は支出するために資金を調達する必要はなく、支出することで新たな資金を生み出すため、「理論上」は財政収入を支出することはできないと主張している。このような財政政策の説明は、例えば、1690年頃にマサチューセッツ州の植民地政府がアメリカで最初の不換紙幣を発行したような、何世紀も前に存在した通貨制度にも適用できるかもしれない。この信用状は経済に使われ、貴金属ではなく納税額と交換された。現代の米国財務省は、1690年代から1700年代の植民地時代の経験に匹敵するような方法で経費を調達しているのだろうか。Fiebiger 2012a, 3) 』

『要するに、「政府」がすべての支出を正味の/新規の貨幣創造によって賄っていると描くことには、その主張が中央銀行にしか適用されない場合には、何の役にも立たないのである(Fiebiger 2013, 66)。』

『MMTの「良心的な無視」/「心配しない」財政分析の問題点の一つは、「キーストローク」というテーマが記述的でないことである。MMTは、財務省が最初に資金を調達せずに資金を支出すると仮定することで、財政政策を前面に押し出している。財務省は銀行ではなく、財政収入を集めなければ、「お金」がないので使うことができない(Fiebiger 2013, 71)。』

『拡張的な財政政策には(人為的に作られたものを除いて)金融的な制約はないということを経済学者や国民に納得させようとする一方で、新表券主義者は結局、逆効果になるような議論を用いている。「政府は銀行口座に入金するだけで支出できる」「財務省はあたかも銀行のように行動できる」「政府の支出は徴税に先行しなければならない」「強力な貨幣創造は長期的には政府の赤字を必要とする」「中央銀行の前金は公共支出と呼べる」「税金や証券の発行は政府の支出を賄うものではない」などと主張しても、ほとんど何の得にもならない。このような直観に反する主張の数々は、政府の財務活動と中央銀行の業務を統合することを前提とした論理に従っており、それによって標準的な用語が変更されている。[...]しかし、MMTは現在、事実と異なる政府と中央銀行の統合に依存した理論で終止符を打っている。これは、単なる(過剰な)単純化の議論を超えている。連結の前提は現実を記述しておらず、標準的な用語を捻じ曲げている(Lavoie 2013, 23) 』

pp.13-14

The critique of lack of descriptiveness misses the point. The consolidation hypothesis does not aim at describing current institutional arrangements, rather, it is a theoretical simplification to get to the bottom of the causalities at play in the current monetary system. It is correct that, under current institutional arrangements, Treasury must receive funds to its account at the central bank before it spends and that this is accomplished through taxes and bond auctions, but that is not the point of MMT when using the consolidation logic. The logic of the argument is about a government sector that combines the central bank and the Treasury into one entity that issues currency. This logic ignores current self-imposed institutional and political constraints on the Treasury and the central bank for three reasons that will be developed in more detail in Section 3: First, the balance sheet outcome is the same regardless of the institutional framework. Second, the impact of Treasury spending, taxing, and bond offering on interest rates and aggregate income is the same with or without consolidation. Third, ultimately, the central bank and the Treasury work together to ensure that the Treasury can always meet its obligations, and that the central bank can smooth interest rates. The central bank is involved in fiscal policy and the Treasury is involved in monetary policy.

Like all theories, MMT makes simplifications that aim at laying bare the foundation of our monetary system once all the political and institutional constraints that government imposes on itself are removed. The consolidation hypothesis and ensuing conclusions are not descriptive, they are logical conclusions. However, that logic was reached after an extensive analysis of the institutional framework of monetarily sovereign governments; it does not result from ivory tower thinking. The logic is important because it can be used to understand current debates about government, and to reframe them in order to provide relevant ways to solve problems for which government intervention may be needed. As shown in the last section, this provides means to cut through the current self-imposed constraints to deal directly with the issues at stake.

拙訳:

記述性に欠けるという批判は、的外れである。統合政府仮説は、現在の制度的な取り決めを記述することを目的としているのではなく、現在の通貨システムで作用している因果関係を突き止めるための理論的な単純化である。現在の制度上、財務省が支出する前に中央銀行の口座に資金を入金しなければならず、それが税金や国債の入札によって実現されていることは正しいが、統合政府仮説の論理を用いた場合のMMTの論点はそこではない。当該議論の論理は、中央銀行と財務省を統合して、通貨を発行する1つの組織にした政府部門についてのことである。この論理は、セクション3で詳しく展開する3つの理由から、財務省と中央銀行に課せられた現在の自縄自縛の制度的・政治的制約を無視している。第一に、バランスシートの結果は制度的枠組みに関係なく同じである。第二に、財務省の支出、課税、債券発行が金利や総所得に与える影響は、統合の有無にかかわらず同じである。第三に、最終的には、中央銀行と財務省が協力して、財務省が常に債務を履行できるようにし、中央銀行が金利を平滑化できるようにする。中央銀行は財政政策に関与し、財務省は金融政策に関与する。

全ての理論がそうであるように、MMTは、政府が自らに課している政治的・制度的な制約をすべて取り除いた後の通貨システムの基盤を明らかにすることを目的とした単純化を行っている。統合政府仮説とそれに続く結論は、記述的なものではなく、論理的な結論である。しかし、その論理は、貨幣主権政府の制度的枠組みを徹底的に分析した上で到達したものであり、象牙の塔の思考から生まれたものではない。この論理は重要である……というのは、政府に関する現在の議論を理解し、政府の介入が必要な問題を解決するための適切な方法を提供するにあたって、議論を再構築するために用いることができるからだ。最後のセクションで示したように、この論理は、現在の自縄自縛の制約を切り抜けて、問題となっている問題に直接対処する手段を提供する。

マサチューセッツのジレンマ……財政スタンスと純貯蓄の欲望

pp.18-19

Second, going back to the Massachusetts dilemma, one can conclude that, as long as the domestic private sector desires to have a net accumulation of government currency, there is no need to retire all of the emitted currency through taxation, i.e. there is no need to have a balanced budget. The question about what the proper federal fiscal stance is at full employment, or other economic states, cannot be determined independently of the non-federal government sectors’ desire in terms of net accumulation of federal government financial assets. [……]

[……]The fiscal balance at full employment will depend on the desired net saving of the nongovernment sectors at full employment income. [……]

[……] However, as national income rises non-discretionary government spending will decline and taxes will rise. This will occur without changing the tax structure and without policy decisions aimed at lowering discretionary spending, but just due to automatic stabilizers. Thus, contrary to what Palley argues, there is no need to proactively raise taxes (i.e. raise tax rates or impose new taxes) and cut spending as the economy does better if strong enough automatic stabilizers are in place. But this does not mean that a surplus is needed during an expansion. To summarize, MMT certainly does not say that at full employment the fiscal position of the government cannot be balanced; it can, but that is not up to the government sector to decide.9

拙訳:

第二に、マサチューセッツのジレンマに戻ると、国内の民間部門が政府通貨の純蓄積を望む限り、放出された通貨をすべて税で償還する必要はない、つまり均衡財政をとる必要はないという結論になる。完全雇用やその他の経済状態において連邦政府の財政スタンスがどうあるべきかという問題は、連邦政府以外の部門における連邦政府金融資産の純蓄積の欲望と無関係には判断できない。……

……完全雇用時の財政収支は、完全雇用所得において非政府部門が望む純貯蓄額に依存する。……

……しかし、国民所得が増加すると、非裁量的な政府支出は減少し、税収は増加する。これは、税制を変えなくても、裁量的な支出を減らすような政策決定をしなくても、自動安定化装置の働きによって起こることである。したがって、Palley氏の主張とは逆に、十分に強力な自動安定装置が働いていれば、景気が良くなったからといって積極的に増税したり(つまり、税率を上げたり、新たな税を課したり)、歳出を削減したりする必要はないのである。しかし、だからといって、景気拡大時に黒字が必要かというと、そうではない。要約すると、MMTは、完全雇用時に政府の財政状態が均衡することはあり得ないとは言っておらず、均衡することは可能だが、それは政府部門が決めることではないということなのだ9。

貨幣主権政府の財政スタンスにおけるMMT的不可知論と留保

pp.19

Third, the previous discussion does not mean that MMT is for a fiscal deficit, nor is it for a fiscal surplus or a balanced budget. MMT is agnostic regarding the fiscal position of a monetarily sovereign government per se. As Abba Lerner’s “functional finance” approach insists, the fiscal position of the government is not a relevant policy objective for a monetarilysovereign government. Price and financial stability, moderate growth of living standards, and full employment are the relevant macroeconomic objectives, and the fiscal position of the government has to be judged relative to these goals. If there is inflation that is demand-led, the fiscal position is too loose (surplus is too small or deficit is too large); if there is non-frictional unemployment, the fiscal position is too stringent. Also if financial fragility grows due to negative net saving by the domestic private sector, the government’s stance is probably too tight.

拙訳:

第三に、これまでの議論においてはMMTは、財政赤字に賛成しているというわけでも、財政黒字や均衡財政に賛成しているわけでもない。MMTは、貨幣的主権を持つ政府の財政的立場それ自体については不可知論である。アバ・ラーナーの「機能的財政」アプローチが主張するように、政府の財政状況は、貨幣主権政府にとって意味のある政策目標ではない。物価と金融の安定、生活水準の適度な向上、完全雇用が関連するマクロ経済目標であり、政府の財政状態はこれらの目標に照らして判断されなければならない。需要主導型のインフレであれば、財政状態はルーズである(黒字が小さすぎるか、赤字が大きすぎる)。また、国内の民間部門の純貯蓄がマイナスになることで金融の脆弱性が高まっている場合、政府のスタンスはおそらくタイト過ぎる。

pp.19

We do not mean to imply that government decisions have no impact. For example, a “trickle up” policy to move income to the rich might increase the private sector’s net saving desire, resulting in bigger budget deficits at full employment; a policy that uses New Deal-style job creation to achieve full employment might instead be consistent with a balanced budget. In other words, government policy can affect the private sector’s behavior.

拙訳:

我々は、政府の決定には何の影響もないと言っているわけではない。例えば、富裕層に所得を移動させる「トリクルアップ」政策は、民間部門の純貯蓄欲求を高め、その結果、完全雇用時の財政赤字が拡大する可能性がある。また、ニューディール型の雇用創出で完全雇用を実現する政策は、逆に財政均衡に整合する可能性がある。要するに、政府の政策が民間企業の行動に影響を与え得る。

国内民間部門の純貸出(net lending)の達成は、政府部門の純借入(net borrowing)を通常必要とする

pp.19-20

A fourth conclusion is that for the stability of the economic system, it is usually important that the domestic private sector not be a net borrower. Indeed, if the domestic private sector is a net borrower, this implies that the amount of net financial assets held by the domestic private sector is declining because borrowing from other sectors grows faster than the gross accumulation of financial claims on other sectors. As a consequence net worth declines unless the nominal value of real asset grows fast enough through asset price appreciation. This is exactly what happened during the recent housing boom when the speculative boom of housing prices was rapid enough to sustain the wealth of households in spite of unprecedented borrowing. Of course, all this is in line with Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis (Tymoigne and Wray 2014). The implication of having a domestic private sector being a net lender is that the federal government sector has to be in deficit unless the foreign sector is willing to be in deficit.1

拙訳:

第4の結論は、経済システムの安定のためには、通常、国内民間部門が純借入をしないことが重要であるということだ。実際、国内民間部門が純借入である場合、国内民間部門が保有する純金融資産額が減少していることを意味する。これは、他部門からの借入が他部門に対する金融債権の総計累積よりも速く増加していることを意味する。その結果、資産価格の上昇によって実物資産の名目価値が十分に上昇しない限り、純資産は減少する。まさにこれが生じたのが直近の住宅ブームで、空前の借り入れにもかかわらず、住宅価格の投機的な上昇が家計の資産を維持するのに十分なほど急速だったのである。もちろん、これらはすべて、ミンスキーの金融不安定性仮説に沿ったものだ(Tymoigne and Wray 2014)。国内の民間部門が純貸出であることの意味するところは、海外部門が進んで赤字にならない限り、連邦政府部門は赤字にならざるを得ないということである1。

通貨における税の位置付け……十分条件と税以外の需要

pp.20

A fifth conclusion, is that, contrary to what Palley, Rochon and Vernengo state, MMT does not believe that the only reason for holding the government currency is because of taxes. Taxes are just a sufficient condition for acceptability of currency—not a necessary condition, however historically taxes and other obligations to authorities did play a central role in the development of modern currency going back at least to Ancient Egypt. Government currency can be held for other reasons as the Massachusetts experiment showed. This is actually why the government can run a deficit as people want to hold government financial instruments (in monetary form or not) beyond the purpose of paying taxes (Wray 2012).

拙訳:

5つ目の結論は、Palley、Rochon、Vernengoが述べているのとは異なり、MMTは政府通貨を保有する唯一の理由が税金であるとは考えていないということである。税金は通貨を受け入れるための十分条件に過ぎず、必要条件ではないが、歴史的には少なくとも古代エジプトまで遡って、税金やその他の政府当局への義務が近代通貨の発展に中心的な役割を果たしていた。マサチューセッツ州の実験が示したように、政府の通貨は他の理由で保有されることもある。それこそが、政府が赤字を出す理由である: 人々は納税の目的を超えて政府の金融商品を(貨幣の形であろうとなかろうと)保有したいと考えるのだ(Wray 2012)。

中央銀行による先行融資(advance)と政府による財政赤字の間の違い

pp.20-21

Sixth, Fiebiger is perfectly correct to state that the previous accounting framework is not enough to understand how financial fragility grows within a specific subsector of the domestic private sector because financial assets and liabilities held within that subsector are eliminated from the analysis above. However, the flow of funds identity helps greatly to conceptualize economic relationships between public and private sectors, which is one of the points of MMT. In addition, MMT does differentiate between saving (in the flow of funds it is the change in net worth: ΔNW) and net saving (saving less investment). Net saving shows how the accumulation of net worth occurs beyond the accumulation of real assets. For the domestic private sector, this comes from a net accumulation of financial claims against the government and foreign sectors. A central point here is that government deficits add to the saving and net saving of the private domestic sector. Lavoie notes:

While it would seem that government deficits in a growing environment are appropriate — as it provides the private sector with safe assets to grow in line with private, presumably less safe, assets — it is an entirely different matter to claim that government deficits are needed because there is a need for cash. Even if the government kept running balanced budgets, central bank money could be provided whenever the central bank makes advances to the private sector. (Lavoie 2013, 9)

This is correct but this is not the point made by MMT. Providing advances does not lead to net saving of government currency as financial assets of the domestic private sector increase by the size of the increase in financial liabilities. Stated another way, advances have to be repaid so the gain in government currency is only temporary. Only a government deficit induced by fiscal policy leads to net saving. Monetary policy can change the composition of net saving by substituting currency for other assets, but it cannot change the size of net saving, i.e. the net accumulation of financial assets. A central bank advances currency into existence while the Treasury spends currency into existence. The difference is important: fiscal policy creates net financial assets; monetary policy only “liquefies” financial assets.

拙訳:

第6に、国内民間部門の特定のサブセクター内で保有されている金融資産・負債が上述の分析から除外されているため、そのサブセクター内で金融の脆弱性がどのように拡大していくのかを理解するには、従来の会計フレームワークでは不十分である、というFiebiger氏の意見は全く正しい。しかし、資金フローの定式化は、MMTのポイントの一つである”公的部門と民間部門の経済的関係の概念化”に大いに役立つ。また、MMTでは、貯蓄(資金フローでは純資産の変化:ΔNW)と純貯蓄(貯蓄から投資を差し引いたもの)を区別している。純貯蓄とは、実物資産の蓄積を逸脱して純資産の蓄積が生ずることを示している。国内の民間部門では、政府や海外部門に対する金融債権の正味の蓄積がそれにあたる。ここでの重要なポイントは、政府の赤字が国内民間部門の貯蓄と純貯蓄を増加させるということだ。Lavoie氏は言うには:

『成長環境下での政府の赤字は適切であると思われる。民間部門に安全な資産を提供し、民間の、おそらく安全性の低い資産に合わせて成長させることができるからだ。しかし、現金が必要だから政府の赤字が必要だと主張するのは、まったく別の問題である。政府がバランスの取れた予算を実行し続けたとしても、中央銀行が民間部門に先行融資を行えば(make advances)、いつでも中央銀行の資金を供給することができるからだ。(Lavoie 2013, 9)』

これは正しいが、これはMMTの問題にしているポイントとは異なる。先行融資(advances)の提供は、国内の民間部門の金融資産と金融負債が同じ分だけ増加するため、政府通貨の純貯蓄にはつながらない。言い換えれば、先行融資は返済しなければならないので、政府通貨の増加は一時的なものとなってしまうのだ。財政政策による政府の赤字のみが純貯蓄をもたらすのである。金融政策は、通貨と他の資産とを交換することで純貯蓄の構成を変えることはできるが、純貯蓄の規模、つまり金融資産の純蓄積を変えることはできない。中央銀行が先行融資を通じて通貨発行するのに対し、財務省は支出を通じて通貨発行する。この違いは重要で、財政政策は純金融資産を創出するが、金融政策は金融資産を「流動化」するだけである。

中央銀行の独立性の限界、財務省との協力/同調義務

pp.26-27

Ultimately, the financial operations of the Treasury and the central bank are so intertwined that both of them are constantly in contact to make fiscal and monetary policy run smoothly. The Treasury gets involved in monetary policy and the central bank gets involved in fiscal policy. As such the independence of the central bank is rather limited and it must ultimately financially support the Treasury in one way or another (Tymoigne 2013). MacLaury from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis summarizes all these points quite nicely:

The central bank is in constant contact with the Treasury Department which, among other things, is responsible for the management of the public debt and its various cash accounts. Prior to the existence of the Federal Reserve System, the Treasury actually carried out many monetary functions. And even since, the Treasury has often been deeply involved in monetary functions, especially during the earlier years. […] Following the 1951 accord between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve System, the central bank was no longer required to support the securities market at any particular level. In effect, the accord established that the central bank would act independently and exercise its own judgment as to the most appropriate monetary policy. But it would also work closely with the Treasury and would be fully informed of and sympathetic to the Treasury's needs in managing and financing the public debt. […] The Treasury and the central bank also work closely in the Treasury's management of its substantial cash payments and withdrawals of Treasury Tax and Loan account balances deposited in commercial banks, since these cash flows affect bank reserves. (MacLaury 1977)

拙訳:

結局のところ、財務省と中央銀行の財務運営は非常に複雑に絡み合っており、財政政策と金融政策を円滑に進めるために、両者は常に連絡を取り合っている。財務省は金融政策に関わり、中央銀行は財政政策に関わる。そのため、中央銀行の独立性はかなり制限されており、最終的には何らかの形で財務省を財政的に支援しなければならない(Tymoigne 2013)。ミネアポリス連邦準備銀行のMacLaury氏は、これらの点を非常にうまくまとめている。

『中央銀行は財務省と常に連絡を取り合っており、財務省は特に、公的債務とその様々な現金勘定の管理に責任を負っている。連邦準備制度ができる前は、財務省が実際に多くの金融機能を担っていた。そして、その後も、特に初期の頃は、財務省はしばしば金融機能に深く関わってきた。1951年に財務省と連邦準備制度との間で結ばれた協定により、中央銀行はもはや証券市場を特定のレベルで支える必要はなくなった。この協定により、中央銀行は独立して行動し、最も適切な金融政策について独自の判断を下すことになったのである。しかし、中央銀行は財務省と緊密に協力し、公的債務の管理と資金調達における財務省のニーズを十分に把握し、同調することになった。財務省と中央銀行は、商業銀行に預けられている財務省の多額の現金支払いとTT&L(Tresury Tax and Loan)勘定の残高の引き出しを管理する際にも密接に協力する。(MacLaury 1977)』

中央銀行と財務省のより記述的な業務説明と統合政府仮説の整合性および意義

pp.27

The central bank and the Treasury must work together to support the monetary and financial systems because they are ultimately two sides of the same coin, the government sector. The most recent example occurred during the recent financial crisis when the Treasury issued bills at the request of the Fed to drain reserves (Tymoigne 2013). Thus, Fiebiger is correct when he notes that:

But it must be acknowledged that, in the modern era, the US Treasury sells bonds to acquire the funds it needs to finance deficit-spending and that without this financing operation would be short of “money” (Fiebiger 2012b, 31)

MMT does not deny this when one accounts for all of the institutional framework. The point is that, in that extreme case where nobody wants to buy bonds from the Treasury, the central bank will intervene, or the Treasury will finds ways to avoid having no funds in their coffers. They have done so for centuries now due to their privilege in the monetary system. They have done so not only to finance Treasury but also to avoid financial instability that results from a federal government that does not perform its monetary duties properly. Thus, if one wants to account for institutional aspects in order to be more descriptive, one should account for all of them, namely those that constrain Treasury-Central Bank operations, and those that allow Treasury to bypass these constraints (Tymoigne 2013). For example, in the US special dealer banks always stand by to purchase treasuries and the Fed ensures there are sufficient reserves to do so by supplying them through temporary repos (a matched purchase of Treasury debt with a requirement that the seller must repurchase later). While the Fed is not in that case directly buying the new issue directly from the Treasury, it uses the open market purchase to buy an existing bond in order to provide reserves needed for a private bank to buy the new security. The end result is exactly the same as if the central bank had bought directly from the Treasury.

拙訳:

中央銀行と財務省は、究極的には政府部門という同じコインの裏表の関係にあるため、金融・財務システムを支えるために協力しなければならない。最近の例では、最近の金融危機の際に、準備預金の除去のため、財務省がFRBの要請に応じて債券を発行したことがあった(Tymoigne 2013)。したがって、Fiebigerが次のように指摘しているのは正しい。

『しかし、現代においては、米国財務省は赤字支出を賄うために必要な資金を得るために債券を販売しており、この資金調達がなければ「貨幣」が不足することを認めなければならない(Fiebiger 2012b, 31)。』

MMTは、すべての制度的枠組みを考慮した場合、これを否定しない。重要なのは、誰も財務省から国債を買いたくないという極端なケースでは、中央銀行が介入するか、財務省が資金不足を回避する方法を見つけるということだ。中央銀行は何世紀にもわたってそうしてきたが、それは通貨システムにおける特権のためだ。中央銀行がそうしてきたのは、財務省に資金を供給するためだけではなく、金融業務を適切に遂行しない連邦政府から生じる金融不安を回避するためでもある。したがって、より記述的にするために制度的側面を考慮するのであれば、財務省と中央銀行のオペレーションを制約するものと、財務省がこれらの制約を迂回することを可能にするものと、すべてを考慮する必要がある(Tymoigne 2013)。例えば,米国ではスペシャルディーラーバンクが常に国債を購入するために待機しており,FRBは一時的なレポ(売り手が後で買い戻さなければならないという条件付きの国債買入)を通じて準備預金を供給することで,国債購入のための十分な準備預金があることを保証している。この場合,FRB は財務省から直接新規銘柄を購入しているわけではないが,民間銀行が新規証券を購入するのに必要な準備預金を提供するために,公開市場での買入を利用して既存の債券を買い入れている。最終的な結果は,中央銀行が財務省から直接購入した場合とまったく同じになる。

pp.28-29

The reader may note that none of the preceding is a theoretical analysis. It is an analysis of balance-sheet accounting and the impact of government spending and taxes on the CB currency supply, as well as an analysis of the interaction between the central bank and the Treasury. However, MMT does draw some theoretical conclusions from the preceding. One of them is that consolidating the central bank and the Treasury in the government sector makes theoretical sense. One could separate the Treasury and central bank instead of consolidating, but this simply adds assumptions and intermediate steps without changing the nature of the operations. Indeed, it has the potential of masking the true nature of the operations, which makes it decidedly less useful as a starting point.

Thus, MMT recognizes that there are some self-imposed constraints on the financial operations of the government. Consider how operations are really done in the US—where the Treasury holds accounts in both private banks (TT&Ls) and the Fed (TGA), but can write checks only on its account at the Fed (it cannot spend bank currency, that is, its deposits at private banks). Further, the Fed is prohibited to be a net buyer of treasuries in the primary market (and is not supposed to allow overdrafts on the Treasury’s account) and thus the Treasury must have a positive balance in its account at the Fed before it spends. Thus, the Treasury must replenish its own account at the Fed either via balances collected from tax (and other) revenues or debt issuance to “the open market”. Fullwiler, Kelton and Wray (2012) have shown that these constraints do not change the end result of fiscal policy in terms of balance sheets, even though the order of financial transactions changes. One way or another, the Treasury gets goods and services in exchange for CB currency. Again the circuit approach improves our understanding of the logic at play. Figure 6 shows the circuit that includes all these institutional aspects.

The circuit is complicated now but, again, before the Treasury can tax and issue bonds, an injection of CB currency must occur first. This is so even though taxes and bond offerings are implemented through bank currency because the Treasury only spends using funds on its TGA. Thus, ultimately taxes and bond offerings drain CB currency when funds are moved from the TT&Ls and the TGA. Either the central bank advances the currency to the domestic private sector or it buys financial assets from that sector. In either case, the CB currency is then passed along to the Treasury, so the central bank is still involved in funding the fiscal operations of the Treasury, but it does so indirectly. In addition, the Federal Reserve provides a stable refinancing source of the Treasury by buying treasuries in the primary market to replace those maturing. To put it simply, the Fed is the monopoly supplier of CB currency, Treasury spends by using CB currency, and since the Treasury obtained CB currency by taxing and issuing treasuries, CB currency must be injected before taxes and bond offerings can occur.

拙訳

読者の皆様には、上記のいずれも理論的な分析ではないことにご留意いただきたい。これはバランスシート会計の分析であり、政府の支出や税金が中央銀行の通貨供給量に与える影響の分析であり、中央銀行と財務省の相互作用の分析でもある。しかし、MMTは前述の内容からいくつかの理論的結論を導き出している。その一つは、中央銀行と財務省を政府部門に統合することは、理論的に意味があるということだ。統合する代わりに財務省と中央銀行を分離することもできるが、これは単に前提条件や中間ステップを追加するだけで、オペレーションの本質は変わらない。むしろ、オペレーションの本質を覆い隠してしまう可能性があり、出発点としての有用性は決定的に低いと言える。

また、MMTでは、政府の財務運営には自らに課した制約があることも認識している。財務省は民間銀行(TT&L)とFRB(TGA ……政府預金)の両方に口座を持っているが、小切手を切ることができるのはFRBの口座に対してのみである(銀行通貨、つまり民間銀行への預金を使うことはできない)。さらに,FRB は主要市場で国債を純購入することが禁止されており(また、財務省の口座への当座貸越を認めないことになっている),したがって財務省は,使用する前に FRB の口座にプラスの残高がなければならない。したがって,財務省は,税収(およびその他の)から徴収した残高か,「公開市場」での国債発行によって,FRBにある自分の口座を補充しなければならないのである。Fullwiler, Kelton and Wray (2012)は,金融取引の順序が変わっても,これらの制約がバランスシートの観点から見た財政政策の最終結果を変えることはないことを示している。いずれにしても、財務省は中央銀行通貨と引き換えに財やサービスを得るのである。ここでも回路的なアプローチによって、作用する論理の理解が深まる。図6は、こうした制度的側面をすべて含む回路を示している。

回路は複雑になっているが、やはり財務省が課税したり債券を発行したりする前に、まず中央銀行通貨の投入が行われなければならない。税金や国債の発行が銀行通貨で実行されても、財務省は政府預金の資金を使ってしか支出しないからである。したがって、最終的に税金や債券発行によって、TT&Lや政府預金から資金が移動すると中央銀行通貨が流出する。中央銀行が通貨を国内の民間セクターに先行融資するか、民間セクターから金融資産を購入するかのいずれかである。いずれの場合も、中央銀行通貨は財務省に渡されるので、中央銀行は財務省の財政運営の資金調達に関与していることになるが、これは間接的なものである。加えて、連邦準備制度は、満期を迎える国債を交換するために国債をプライマリー市場で購入することで、財務省に安定した借り換えの源泉を提供している。簡単に言えば、FRBは中央銀行通貨の独占的な供給者であり、財務省は中央銀行通貨を使って支出を行い、財務省は課税と国債発行によって中央銀行通貨を入手するので、課税と国債発行が行われる前に中央銀行通貨を注入しておかなければならない。

統合政府仮説の必要性とECB/ユーロの特殊性

pp.29-31

Lavoie is actually on the same page and recognizes that the fact that central bank cannot directly finance the Treasury does not change the logic at play. However, he prefers not to use the consolidated government:

In a nutshell, as long as the other characteristics of a “sovereign currency” are fulfilled, it makes little difference, as the cases of Canada and the USA illustrate, whether the central bank makes direct advances and direct purchases of government securities or whether it buys treasuries on secondary markets, as long as the central bank shows determination in controlling interest rates. […] But then, if it makes no difference, why do neochartalists insist on presenting their counter-intuitive stories, based on an abstract consolidation and an abstract sequential logic, deprived of operational and legal realism. (Lavoie 2013)

MMT argues that the added complexity is counter-productive because it leads to poor understanding among economists, poor modeling, and bad policy choices. Were economists and policy makers to understand that the MMT consolidated case explains the underlying nature of government debt operations, we suggest that all three could be markedly improved. Finally, MMT insists that there is nothing “natural” about the operating procedures (including restrictions) adopted—since in practice they make no difference they could be dropped to simplify procedures. So the difference with Lavoie is partly a strategic difference but also partly a way to look at—and possibly improve—policy making as shown in section 5.

In conclusion, Treasury spending always involves monetary creation as private bank accounts are credited, while taxation involves monetary destruction as bank accounts are debited. The question becomes how the Treasury acquired the deposits it has in its account at the central bank. In the current institutional framework, the apparent answer is through taxation and bond offerings. While usually economists stop here, MMT goes one step further and wonders where the receipts of taxation and bond purchases came from; the answer is from the central bank. This must be the case because taxes and bond offerings drain CB currency so the central bank had to provide the funds (as it is the only source). The logical conclusion is then that CB currency injection has to come before taxes and bond offerings. Close study of the operations involved reveals that the CB either advances them, or more commonly, provides them through open market purchases. More broadly, the theoretical insight that MMT draws is that government spending (by the Treasury or spending and lending by the central bank) must come first, i.e. it must come before taxes or bond offerings. Spending is done through monetary creation ex-nihilo in the same way a bank lends (buying financial assets) by crediting bank accounts; taxes and bond offerings lead to monetary destruction (L1 goes down) in the same way that loan repayments destroy bank deposits.

One may note that most of these conclusions also apply to the Eurozone but there are specific institutional aspects that make the Eurozone Treasuries non-monetarily sovereign (Figure 7). First, there is no direct coordination of Eurozone Treasuries with the ECB for monetary and fiscal policy purposes (indeed this is prohibited). Second, Eurozone Treasuries are not allowed to issue any monetary instrument whereas the US Treasury issues coins to the Federal Reserve in exchange for TGA crediting at par value.14 And the US Treasury can issue coins of any denomination. Third, the ECB does not perform unconditional outright purchases and sales of Eurozone Treasuries. At least, before the Securities Market Programme and Outright Market Transactions program, the ECB did not perform any outright transactions on Treasuries. Thus, if Eurozone Treasuries are in trouble, they have no means to bypass existing self-imposed constraints short of leaving the Eurozone. Finally, the ECB does not provide a refinancing source to the Eurozone Treasuries. This does not mean that the ECB is not involved indirectly, as the Target 2 clearing mechanism operates to provide euro reserve balances to member central banks. This has always provided something of a “relief valve” for member state fiscal operations because national central banks do purchases treasuries in secondary markets. While the ECB has been reluctant to buy treasuries, it deals with national central banks on demand so the ECB is again indirectly involved in the funding of national Treasuries, albeit in a more narrow and cumbersome way.

拙訳:

Lavoieも同じ考えを持っており、中央銀行が財務省に直接資金を提供できないという事実は、この論理を変えるものではないと認識している。しかし、彼は統合政府を用いないことを好んでいる:

『一言で言えば、「主権通貨」の他の特徴が満たされている限り、カナダやアメリカの事例が示すように、中央銀行が金利をコントロールする決意を示している限り、中央銀行が国債を直接融資したり、直接購入したりしても、流通市場で国債を購入しても、ほとんど違いはないのである。しかし、もし違いがないのであれば、なぜ新表券主義者は、抽象的な連結と抽象的な順序論理に基づいて、運用上および法律上のリアリズムを欠いた、直感に反するストーリーを提示することにこだわるのだろうか。(Lavoie 2013)』

MMTが主張しているのは、複雑さが増すことは、経済学者の理解が妨げられ、モデル化を失敗させ、誤った政策選択につながるため、非生産的であるということである。経済学者や政策立案者が、MMTの統合ケースが政府債務の運用の基本的な性質を説明していることを理解すれば、上記の3つの点は著しく改善されると我々は提案する。最後に、MMTは、採用されたオペレーション手順(制約を含む)には何の「自然」もないと主張している。このように、Lavoieとの違いは、戦略的な違いであると同時に、第5節で示すように、政策立案の見方(及び改善の仕方)の違いでもあるのだ。

結論として、財務省の支出は常に民間の銀行口座に入金される貨幣の創造を伴い、課税は銀行口座から引き落とされる貨幣の破壊を伴う。問題は、財務省が中央銀行の口座にある預金をどのようにして取得したかである。現在の制度的枠組みの中では、税金と国債の発行がその表面的な答えになる。通常の経済学者はここで議論を終わらせているが、MMTはさらに一歩進んで、税金や国債の購入による収入はどこから来たのかと考察する。それによれば、税金や債券発行が中央銀行通貨を流出させるため、中央銀行が資金を提供しなければならなかった(それが唯一の供給源であるため)という具合になる。論理的には、税金や国債発行よりも先に中央銀行通貨を投入しなければならないということになるのである。関連するオペレーションを詳細に検討すると、中央銀行が資金を投入するか、より一般的には公開市場での購入を通じて資金を提供することがわかる。より広く言えば、MMTが導き出す理論的洞察は、政府の支出(財務省によるもの、あるいは中央銀行による支出や貸出)は最初に行われなければならない、つまり税金や国債の発行よりも先に行われなければならないというものである。支出は、銀行が銀行口座に入金して貸し出す(金融資産を購入する)のと同じように、自力で貨幣を創造することによって行われ、税金や国債の発行は、ローンの返済が銀行預金を破壊するのと同じように、貨幣の破壊(L1の減少)につながる。

これらの結論のほとんどはユーロ圏にも当てはまるが、ユーロ圏の国債が非貨幣的主権であることを示す特定の制度的側面があることに注意してほしい(図7)。第一に,ユーロ圏の国債は,金融政策や財政政策のためにECBと直接連携することはない(実際に禁止されている)。第二に、ユーロ圏の財務省はいかなる金融商品も発行することができないが、米国財務省は同額の政府預金と引き換えに連邦準備制度理事会にコインを発行している14。第三に、ECBはユーロ圏の国債を無条件で買い取り、売り渡すことはしない。少なくとも、証券市場プログラムやアウトライト市場取引プログラムが導入される前は、ECBは国債のアウトライト取引を行っていなかった。そのため、ユーロ圏の国債に問題が発生した場合、ユーロ圏から離脱する以外に、既存の自己規制を回避する手段がない。最後に、ECBはユーロ圏の国債に借り換えの手段を提供していない。しかし、ECBが間接的に関与していないわけではない。Target 2の決済メカニズムは、加盟国の中央銀行にユーロの準備預金残高を提供するために機能している。各国の中央銀行が流通市場で国債を購入しているため、これは常に加盟国の財政運営に「救済弁」のようなものを提供してきた。ECBは国債の購入には消極的だが、各国の中央銀行とオンデマンドで取引しているため、より狭く煩雑な方法ではあるが、各国の国債の調達に間接的に関与してはいる。

国債発行の意義における合意

pp.32-33

Beyond the relevance of the consolidation of the central bank and Treasury for theoretical purpose, one can draw additional conclusions from the interaction between the central bank and Treasury in monetarily sovereign governments. First, Treasury has issued securities for purposes other than funding itself. One reason is to provide a means of payment to the country, another is to help the central bank in its interest-rate stabilization operations, and a third is to help financial institutions meet their capital requirements and to provide a foundation upon which all other securities are valued by providing a proxy for the risk-free rate. MMT argues that these reasons for issuing treasuries are much more relevant in a monetarily sovereign government, because they do not result from a self-imposed constraint. They respond to a genuine need of the economic system. Palley notes that bonds provide an important foundation for the financial system but does not seem to recognize that MMT agrees (Palley 2013, 22). Bond offerings by the Treasury are central to the stability of the financial system as long as the central bank does not pay interest on reserves. Interest-paying government liabilities are so important that Treasury may continue to issues treasuries for that purpose even if there is a fiscal surplus. Australia is a recent example of that case (Commonwealth of Australia 2003, 2011). China is an example of a case in which it is the central bank that issues interest-paying bonds when the Treasury runs a surplus.

拙訳:

中央銀行と財務省の統合が理論的に妥当であることはもちろんだが,貨幣主権政府における中央銀行と財務省の相互作用からは,さらに別の結論を導き出すことができる。まず,財務省は自らの資金調達以外の目的で証券を発行している。一つは国への支払い手段を提供するため、もう一つは中央銀行の金利安定化オペレーションを支援するため、もう一つは金融機関の自己資本規制を支援するため、そしてリスク・フリー・レートの代理を提供することで他のすべての証券が評価される基盤を提供するためである。MMTは、国債を発行するこれらの理由は、貨幣的主権を持つ政府ではより重要であると主張する。経済システムの真の必要性に応えるものだからだ。Palley氏は、債券が金融システムの重要な基盤となっていることを指摘しているが、MMTもそれに同意していることを認識していないようだ(Palley 2013, 22)。中央銀行が準備預金付利を行わない限り、財務省による債券の発行は金融システムの安定の中心となる。利子を支払う政府負債は非常に重要であるため、財務省は財政が黒字であってもその目的で国債を発行し続けることがある。最近では、オーストラリアがその例である(Commonwealth of Australia 2003, 2011)。中国は、財務省が黒字の時に中央銀行が利払い国債を発行する例である。

中央銀行において重要なのは、その負債額ではなく構成である

pp.34-35

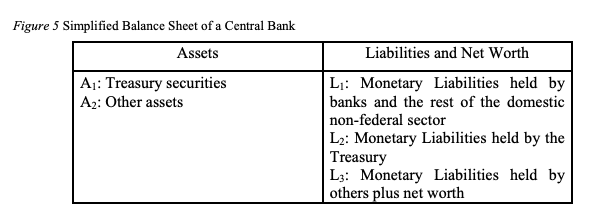

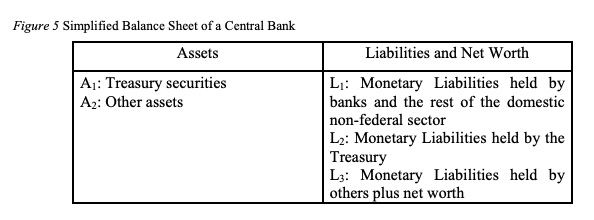

Fiebiger also takes issue with the exclusion of TGA from the definition of the money supply and argues that looking at L1 alone is not relevant. Net monetary creation would mean that the liability of the central bank goes up, when in fact when the Treasury spends L2 goes down by the same amount as L1 goes up.

MMT description of the money supply process [involves] arbitrary accounting practices; in particular, [and leads] to the mislaid belief that the Treasury’s account at the central bank can be “ignored” because the deposits are not ‘counted’ in any money stock measure and ‘net out’ when the public sector’s books are consolidated. (Fiebiger 2012a, 2)

When the Treasury spends the transaction only alters the composition of central bank liabilities and, therefore, is not money creation. (Ibid, 3)

There are several points here. First, taxes and bond offerings drain CB currency as funds collected from them are moved into the Treasury’s account at the Fed. It does not matter that banks are not the main participants in the primary market. The important step is when the funds obtained are moved into the TGA because this leads to a drain of CB currency from the nonfederal sector, which normally leads to a higher FFR unless the central bank intervenes. Second, Treasury spending injects reserves and this is the important point; or put in Fiebiger’s words, the change in the composition of the central bank liabilities is what matters, not the amount of liabilities of the Fed (except in the case of consolidation). The amount of central bank liabilities held by the domestic private sector increases, while the amount of central bank liabilities held by the Treasury goes down. Thus, contrary to what Fiebiger states, it is not that MMT relies on statistical definitions of money to argue that a change in L2 is not the relevant variable to study. It is changes in L1 that matters for economic analysis of a domestic economy because they reflect the interactions between the federal and non-federal sectors.

拙訳:

Fiebiger氏はまた、マネーサプライの定義から政府預金を除外していることを問題視し、L1だけを見ても意味がないと主張している。純然たる通貨創造は、中央銀行の負債が増加することを意味するが、実際には財務省が支出すると、L1が増加するのと同じ量だけL2が減少する。

『MMTによる貨幣供給プロセスの説明には、恣意的な会計処理が含まれている。特に、中央銀行に対する財務省の口座は「無視」できるという誤った信念につながっている。なぜなら、この預金はマネーストックの測定には「カウント」されず、公共部門の帳簿を連結する際に「相殺」されるからだと。(Fiebiger 2012a, 2)』

『財務省が支出しても、その取引は中央銀行の負債の構成を変えるだけであり、したがって貨幣の創造ではないのだ。(同上、3)』

ここにはいくつかの論点がある。第一に,税金と国債発行によって集められた資金がFRBにある財務省の口座に移されることで,中央銀行の通貨が流出すること。当該銀行がプライマリー・マーケットの主な参加者でないことは問題ではない。重要なステップは,得られた資金が政府預金に移されたときである。なぜなら,これは非連邦部門からの中央銀行通貨の除去につながり,中央銀行が介入しない限り,通常はFFレートの上昇につながるからである。第二に、財務省の支出は準備預金を注入するが、これは重要な論点である。あるいは、Fiebigerの表現法を借りれば、中央銀行の負債構成の変化が重要なのであって、FRBの負債額の変化が問題なのではない(統合政府の場合は除く)。国内の民間部門が保有する中央銀行の負債額は増加する一方で、財務省が保有する中央銀行の負債額は減少する。このように、Fiebiger氏が述べているのとは逆に、MMTが貨幣の統計的定義に依拠して「L2の変化は研究すべき関連変数ではない」と主張しているわけではない。国内経済の経済分析にとって重要なのはL1の変化だ。なぜならそれは、連邦部門と非連邦部門の間の相互作用を反映しているからである。

ゼロ金利政策下における国債発行は統合政府仮説の反証にならない

pp.36

In the same vein of confusing the consolidation hypothesis with a descriptive approach, Fiebiger asks why the Treasury continued to emit bonds when the FFR was effectively zero after 2009:

Why then has the US Treasury continued to issue bonds in the period 2009-2011Q2 (equal to $3,377bn) even though it had no reason to do so – according to MMT – because the fed funds rate was effectively zero and the Federal Reserve acquired the power to pay interest on reserves? If bond sales are a ‘voluntary’ part of fiscal policy and not needed since late 2008 for the ‘designed’ purpose of ‘interest rate maintenance’ operations, then, why did the US Treasury still issue bonds even though it bumped into the congressional ‘debt ceiling’ and nearly defaulted on its financial obligations in August 2011? (Fiebiger 2012, 6)

The first part of the answer is because the Treasury needs to fund itself according to existing procedures that we have discussed in detail—procedures that can be changed or eliminated, and indeed, are occasionally changed. However, the second part, is that during the period of time that the Fed was operating a phase of Quantitative Easing, the Federal Reserve asked the Treasury to issue bills for the purpose of draining reserves and maintaining the FFR on target (which was near zero but positive)—and it used the Supplementary Financing Program (SFP) for such purposes. It did so even after the FFR was close to zero and even after the Fed began to pay interest on reserves because these bills helped to drain a large amount of reserves and because not all institutions with an excess of Federal Reserve currency could get a reserve account at the Fed (Tymoigne 2013). In other words, SFP bills were issued for monetary policy purpose. As stated above, treasuries have been issued for purposes other than financing spending, and MMT argues that these other purposes are more relevant. While we will not go into details, it appears that the US Treasury issues longer maturity debt because the private wealth managers want it in their portfolios. That could be a legitimate purpose for issuing long term Treasury debt.15

拙訳:

統合政府仮説と記述的アプローチを混同しているのと同じ文脈で、Fiebigerは、2009年以降、FFレートが事実上ゼロになったときに、なぜ財務省が国債を発行し続けたのかを問うている:

『MMTによれば、FFレートが事実上ゼロになり、連邦準備制度が準備金に利息を支払う権限を得たため、2009年から2011年のQ2の期間に米国財務省が債券を発行する理由がないにもかかわらず、財務省はなぜ債券を発行し続けたのだろうか(3兆3770億ドルに相当)。もし国債の売却が財政政策の「任意」の部分であり、「金利維持」操作という「意図された」目的のために2008年後半から必要とされていないのであれば、なぜ米国財務省は2011年8月に議会の「債務上限」にぶつかり、金融債務の不履行になりそうになったにもかかわらず、依然として国債を発行したのだろうか。(Fiebiger 2012, 6)』

答えの最初の部分は、財務省が、これまで詳細に説明してきた既存の手続きに従って資金を調達する必要があるからだ。この手続きは、変更や廃止が可能であり、実際に時折変更されている。しかしながら、第2の部分は、FRBが量的緩和を行っていた期間、FRBは準備預金を除去し、FFレートを目標値(ゼロに近いプラス)に維持する目的で財務省に債券の発行を要請し、補完的資金調達プログラム(SFP)のために利用していたということである。FFレートがゼロに近づいた後でも、FRBが準備預金に利子を支払うようになった後でもこのようなことをしたのは、これらの手形が大量の準備預金を除去するのに役立ち、また、連邦準備通貨が余っているすべての機関がFRBに準備預金口座を持てるわけではなかったからである(Tymoigne 2013)。言い換えれば,SFP 債券は金融政策目的で発行されたものである。前述のように、国債は支出の資金調達以外の目的で発行されており、MMTはこのような他の目的の方がより意味があると主張している。詳細は割愛するが、米国財務省が長期債を発行しているのは、プライベート・ウェルス・マネージャーがそれをポートフォリオに入れたいからだと思われる。これは、長期国債を発行する合理的な目的であると言えるだろう15。

MMTにおける内生的貨幣供給……中央銀行通貨の”レバレッジ”と貨幣乗数否定

pp.36-37

While all these aspects relate to the fiscal and monetary policy impacts on reserves, it does not say anything about how private banks operate. Post Keynesians have worked extensively on that issue and so it is sufficient to say that the supply of bank currency is endogenous and is not based on a multiplier. The private banking sector, however, does leverage CB currency. In the world of finance, “to leverage” signifies being able to take a position in an asset without having to provide all or any funds for the position. Banks necessarily leverage CB currency, because they acquire asset position by issuing financial instruments that promise to deliver CB currency on demand or on some contingency at a later date. They do not have to have any CB currency now to make this promise. Thus statements like: “For chartalists, state money is exogenous, and credit money is a multiple of the former” (Rochon and Vernengo 2003, 61) is not correct and simply reflects a misunderstanding of the way that terms like “leverage” are used by financial markets participants.16 Fiscal operations result in exogenous fluctuations of CB currency, in the sense that they do not result from a demand from banks. In addition, all “state money” is also “credit money” so the difference is not relevant: all monetary instruments are financial instruments; they are all monetary claims that promise to do something. Government just promises to take back its currency on demand, while private currencies also promise to convert into government currency on demand or on some specified contingency.

拙訳:

これらの点はすべて、財政政策と金融政策が準備金に与える影響に関連しているが、民間銀行がどのように運営されているかについては何も述べていない。ポスト・ケインジアンはこの問題について広範囲に取り組んできたので、銀行通貨の供給は内生的であり、乗数に基づくものではないと言えば十分であろう。しかし、民間銀行セクターは中央銀行通貨にレバレッジをかけている。金融の世界では、「レバレッジをかける」とは、ある資産のポジションを取る際に、そのポジションのためにすべての資金を提供する必要がないことを意味する。銀行は、要求に応じて、あるいは将来の偶発的な状況に応じ中央銀行通貨を提供することを約束する金融商品を発行して資産ポジションを取得するのであり、これは必然的に中央銀行通貨のレバレッジということになる。この約定にあたり、今現時点で中央銀行通貨を保有している必要はない。したがって、次のような記述:「表券主義者にとって、国家貨幣は外生的であり、信用貨幣は前者の倍数である」(Rochon and Vernengo 2003, 61)というのは正しくなく、単に金融市場の参加者が用いている「レバレッジ」と混同して誤解していることを反映している16。また、すべての「国家貨幣」は「信用貨幣」でもあるので、その区別に意味はない。すべての貨幣代替物は金融商品であり、何かを約束する金融債権である。政府は要求に応じて自国の通貨を引き取ることを約束するだけであり、民間通貨も要求に応じて、あるいは特定の事態に応じて政府の通貨に交換することを約束するだけなのだ。

税金を払っていないのに通貨を受け入れる個人の存在、及び税金として用いられていないのに受容・重用される外貨の存在は、いずれもMMTの反証にはならない

pp.37-8

4. ADDING THE FOREIGN SECTOR

Palley notes that government currency is demanded for reasons other than paying taxes and that foreigners who may want to hold the domestic (foreign to them) currency do not pay taxes to the domestic government. In addition, in some countries the domestic private sector does not want to use the domestic government currency in many, or even most, economic transactions even though the government is imposing a tax; thus taxes do not drive currency.

MMT has always made both of these points, indeed, they are critical to understanding MMT. Note that even within a sovereign nation there are individuals who do not owe taxes but still accept the national currency, and foreign currencies can be accepted domestically even though there are no domestic taxes in those currencies. And in some countries there are things for sale only in foreign currencies. All of these situations have been discussed in length by MMT. (Wray 1998) None of this causes problems for MMT. The simple fact is that almost all monies of account are “state monies” and almost all government currencies do have taxes or other obligations standing behind them. Further, even if one can find a money of account and a currency that has no fee, fine, tax, tribute, or tithe backing it, that would not invalidate MMT. Perhaps Palley does not understand the difference between “necessary” and “sufficient” conditions: a tax (or other involuntary obligation) is sufficient to drive a currency; it might not be necessary. MMT theory relies on the sufficient condition, not the necessary condition. There is no part of MMT theory that relies on the necessary condition. Even if Palley could uncover dozens of currencies driven without fees, fines, tithes, tribute or taxes, it would in no way invalidate MMT. It is curious, however, that so far as we know, he has found none that is documented to the standard that a serious researcher would desire.

拙訳:

4. 海外部門の追加

Palley氏は、政府通貨は納税以外の理由で需要があり、国内(彼らにとっては外国)の通貨を持ちたいと思う外国人は、国内政府に税金を払っていないと指摘する。また、一部の国では、政府が租税を課しているにもかかわらず、国内の民間部門が多くの、あるいはほとんどの経済取引で国内の政府通貨を使いたがらないこともあり、租税が通貨を動かすことはないと主張している。

MMTはこの2つの点を常に指摘しており、実際、MMTを理解する上で重要なポイントとなっている。注意してほしいのは、主権国家においても、税金を払っていないにも関わらず国の通貨を受け入れる個人はいるし、国内で税金として用いていなくても外国の通貨が国内で受け入れられることもある。また、国によっては、外貨でないと売れないものもある。これらの状況はすべて、MMTで長々と議論されてきた。(Wray 1998) これらはいずれもMMTにとって問題とはならない。単純な事実として、ほとんどすべての会計上の貨幣は「国家貨幣」であり、ほとんどすべての政府通貨はその背後に租税やその他の義務を負っている。さらに、たとえ手数料や罰金、租税、年貢、十分の一税などの裏付けがない貨幣や通貨を見つけたとしても、MMTが無効になるわけではない。おそらくパレー氏は、「必要条件」と「十分条件」の違いを理解していないのだろう。租税(またはその他の非自発的な義務)は、通貨を動かすのに十分ではあるが、必要ではないかもしれない。MMT理論は必要条件ではなく、十分条件に依存している。MMT理論には、必要条件に依存している部分はない。たとえPalleyが、手数料、罰金、十分の一税、年貢、税金なしで動いている何十もの通貨を発見したとしても、MMTが無効になることはないだろう。しかし、不思議なことに、私たちが知る限りでは、真面目な研究者が望む基準で文書化された形では、そうした通貨は一つも見つかっていない。

海外部門に対する自国通貨発行の独占性と、「国内支出」から「外国人貯蓄」へという順序、及び外貨建て負債や通貨ペッグによる債務危機

pp.38-39

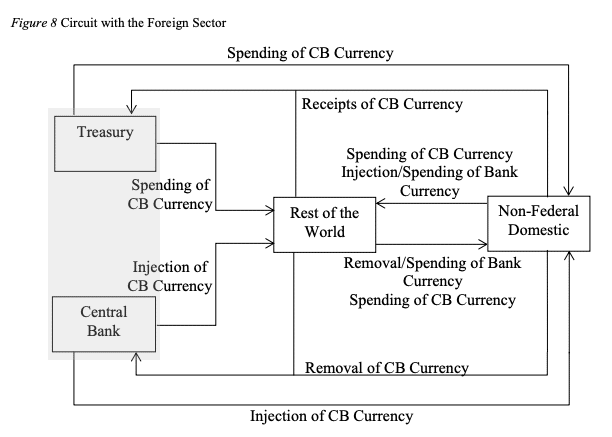

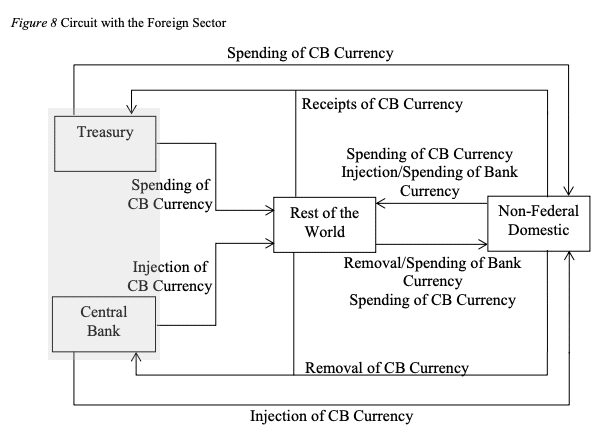

In this section operations with the foreign sector added are studied from the point of view of MMT. With the foreign sector added, we get the circuit in Figure 8. Some of the complexities presented in the previous section have been removed to get to the point.

Foreigners can create financial instruments denominated in the domestic unit of account that promise to deliver domestic (foreign to them) government currencies, but they cannot legally create that currency. All domestic currencies come from the domestic economy either from the federal government (government currency) or from the non-federal government (for example, bank deposits). It makes no sense to argue that foreigners supply US dollars to the US government. As foreigners cannot create US dollar currency, they must obtain it from the US. While it is true that a foreign bank can create US dollar deposits (which is done in the “Eurodollar” market), these must obtain “real US dollars” for cash withdrawals and clearing, which can only come from the US Fed or Treasury. Most of the time, when a foreigner provides US dollars to the US government (that is, by purchasing a treasury) the payment is made by debiting the foreigner’s reserve account at the Fed. The foreigner’s holding of the purchased treasury is really just a different electronic entry, also at the Fed. The “borrowing” of dollars is just a shift on the Fed’s balance sheet.

拙訳:

本節では、海外部門を加えたオペレーションをMMTの観点から検討する。海外部門を加えた場合、図8のような回路になる。前節で紹介した複雑な部分を削除して、要点をまとめた。

外国人は、国内(彼らにとっては外国)の政府通貨を交付することを約束した国内の会計単位建ての金融商品を作ることはできるが、その通貨を合法的に作ることはできない。すべての国内通貨は、連邦政府(政府通貨)か非連邦政府(例えば銀行預金)のいずれかによって国内経済からもたらされる。外国人がアメリカ政府に米ドルを供給していると主張しても意味がない。外国人は米ドルの通貨を作ることができないので、米国から米ドルを入手しなければならない。外国の銀行が米ドル預金を作ることができるのは事実だが(これは「ユーロダラー」市場で行われている)、これらは現金の引き出しや清算のために「本物の米ドル」を入手しなければならず、それは米国のFRBや財務省からしか得られない。ほとんどの場合、外国人がアメリカ政府に米ドルを提供する(つまり、財務省証券を購入する)とき、その支払いは外国人のFRBの準備口座から引き落とされることによって行われる。外国人が購入した財務省証券を保有しているといっても、それは実際にはFRBでの別の電子入力にすぎない。ドルの「借り入れ」は、FRBのバランスシート上での移動にすぎないのだ。

pp.40-41

Again the causality goes from spending by the domestic economy to saving by foreigners. Thus, a monetarily sovereign government does not need foreigners to fund itself. While the Treasury sells bonds to obtain CB currency, the central bank is the entity that ultimately issues the currency, not foreigners. “China” does not finance the “US.” It is the “US” that provides the dollars that “China” wants. Because China has accumulated so many dollar reserves (reserve accounts at the Fed plus holdings of US treasuries), it is true that she can buy new issues of US Treasuries using accumulated dollar reserve holdings. But that cannot be a net source of US government finance, rather, it represents a portfolio change—perhaps an exchange of reserve deposits at the Fed for US treasuries. US indebtedness does not change by this portfolio adjustment, although since the term structure of interest rates is usually positive, this transaction would increases payment commitments. However, those interest payments will be made—in the future—in the same way that all other government spending is made, through credits to the foreigner’s account at the Fed. There is nothing “special” about payments to foreigners, because the US government makes commitments in its own currency.

For a monetarily sovereign government, a debt crisis is a choice to default not an inability to make a promised payment. A debt crisis for economic reasons can occur if a government promises to deliver a foreign currency or if a government has to defend a currency peg. For a sovereign nation that does not promise to peg, there is no process that can lead to involuntary default, although as the US Congress is proving, default by choice remains a possibility. Now, none of this applies if a national government issues financial instruments denominated in a foreign currency—a point we have always made (indeed, it was the main reason why we criticized the formation of the EMU from inception (Wray 2003b)). Fiebiger does not seem to understand that this is a point made by MMT:

Those crises strongly support an alternative view that the critical issue when it comes to macro policy autonomy is not adoption of a “flexible exchange rate” but the currency denomination of external liabilities; and, the extent to which a nation’s currency is utilized by other nations as international money. (Fiebiger 2013, 72)

This is exactly what MMT says. MMT goes further by noting that some governments, like Hungary, can issue their own currency and have control over the interest rate but may choose to issue foreign-denominated debt, which creates problems (Mitchell 2012). Indeed, some who advocate MMT—including Wray—have argued that no sovereign government should be allowed (by its citizenry) to issue IOUs denominated in foreign currency. The position should be clear: MMT argues that sovereign currency increases policy space, so issuing debts in foreign currencies should be avoided. Fiebiger has apparently misunderstood the MMT position. However, the Palley-Fiebiger critique certainly could be applied to others—even if it cannot be applied to MMT. The exchange rate regime also plays a role in a debt crisis, because countries that only issue financial instruments denominated in the domestic unit of account may default if they feel their currency peg is threatened: Russia did so in the early 2000s.

拙訳:

ここでも因果関係は、国内経済による支出から外国人による貯蓄へ、という順序になる。したがって、貨幣的主権を持つ政府は、自らの資金調達のために外国人を必要としない。財務省は中央銀行通貨を手に入れるために債券を売るが、最終的に通貨を発行するのは中央銀行であり、外国人ではない。「中国」が「米国」に資金を提供するわけではない。「中国」が欲しいドルを提供するのが、「米国」なのである。中国は多くのドル準備(FRBの準備金と米国債の保有)を蓄積しているので、蓄積したドル準備を使って米国債の新規発行を買うことができるのは事実である。しかし、それは米国政府の資金調達の純粋な源泉とはなりえず、それよりむしろポートフォリオの変更を意味するのであり、おそらくはFRBの準備預金と米国債の交換を意味することになる。このようなポートフォリオの調整によって米国の負債水準は変化しないが、金利の期間構造は通常プラスであるため、この取引によって支払いの約束が増えることになる。しかし,これらの利払いは,他のすべての政府支出が行われるのと同じ方法で,将来,FRBの外国人口座への入金を通じて行われる。外国人への支払いには何の「特殊性」もない。アメリカ政府は自国の通貨で約束をしているに過ぎないのだから。

貨幣的主権を持つ政府にとって、債務危機とはデフォルト(債務不履行)を選択することであり、約束した支払いができないことではない。経済的理由による債務危機は、政府が外国通貨の交付を約束した場合や、政府が通貨ペッグを守らなければならない場合に起こりうる。ペッグを約束していない主権国家には、非自発的なデフォルトにつながるプロセスはないが、米国議会が証明しているように、選択によるデフォルトは依然として可能性がある。しかし、政府が外国通貨建ての金融商品を発行している場合には、上記の説明はあてはまらない。この点については、我々は常に指摘してきた(実際、私たちが経済通貨同盟の形成を当初から批判していた主な理由はこの点であった(Wray 2003b))。Fiebigerは、この点がMMTの指摘であることを理解していないようだ。

『これらの危機は、マクロ政策の自律性に関する重要な問題は、「変動為替レート」の採用ではなく、対外負債の通貨表記であり、一国の通貨が国際通貨として他国に利用される程度であるという代替的な見解を強く支持している。(Fiebiger 2013, 72)』

これはまさにMMTが主張していることだ。MMTはさらに、ハンガリーのように、自国通貨を発行して金利をコントロールできるにも関わらず、外国建ての債務を発行することを選択する政府の場合もあり、それが問題を引き起こすと指摘している(Mitchell 2012)。実際、WrayをはじめとするMMTの提唱者は、いかなる主権政府も(その国民によって)外貨建てのIOUを発行することを許されるべきではないと主張している。MMTは主権通貨が政策スペースを拡大すると主張しており、外貨建ての債務を発行することは避けるべきだという立場を明確にしている。Fiebiger氏は明らかにMMTの立場を誤解している。しかし、Palley-Fiebigerの批判は、MMTには適用できなくても、他の人々には適用できるであろう。為替レート体制もまた、債務危機にて重要となる。なぜなら、国内の通貨単位でしか金融商品を発行していない国であっても、通貨ペッグが脅かされていると感じると、デフォルトに陥る可能性があるからである。2000年代初頭のロシアがそうだった。

自国通貨建て債務の不履行の実際と、技術的デフォルトの無意義性

pp.41

Credit rating agencies provide a rating for the national government of all countries regardless of the monetary system in place. In its 2007 Sovereign Debt Primer, Standard and Poor’s explains how the rating is determined.

A sovereign rating is a forward-looking estimate of default probability. […] The key determinants of credit risk [are economic risk and political risk]. Economic risk addresses the government’s ability to repay its obligations on time and is a function of both quantitative and qualitative factors. Political risk addresses the sovereign’s willingness to repay debt. Willingness to pay is a qualitative issue that distinguishes sovereigns from most other types of issuers. Partly because creditors have only limited legal redress, a government can (and sometimes does) default selectively on its obligations, even when it possesses the financial capacity for timely debt service. (Standard and Poor’s 2007, 1, 3-4)

MMT agrees that a monetarily sovereign government can willingly default on its currency for both economic and political reasons. Cantor and Parker (1995) provide examples of governments that defaulted on debts denominated in their own unit of account, and note that “Domestic currency defaults have usually been the result of an overthrow of an old political order—as in Russia and Vietnam—or the byproduct of dramatic economic adjustment programs aimed at curbing hyperinflation—as in Argentina and Brazil” (Cantor and Parker 1995, 3). However, Cantor and Parker also note that this type of default is rare. If one had to estimate a default probability on monetarily sovereign governments, it would be much lower than the historical 0.02 percent five-year median default probability used for AAA corporate bonds. One could argue that it would be so low as to make it irrelevant, which is what MMT argues.17

格付け会社は、通貨制度にかかわらず、すべての国の政府に対して格付けを行っている。スタンダード&プアーズは、2007年に発行した『ソブリン・デット・プライマー』の中で、格付けの決定方法について説明している:

『ソブリン格付けは、デフォルト確率の将来的な推定値である。信用リスクの主な決定要因は、経済的リスクと政治的リスクである。経済的リスクは、政府が債務を期限内に返済する能力を示すもので、量的および質的な要因の両方の機能を持っている。政治的リスクは、政府が債務を返済する意思があるかどうかを示すものだ。支払い意思は質的な問題であり、ソブリンは他の多くのタイプの発行体とは異なる。債権者の法的救済手段が限られていることもあり、政府はタイムリーに債務を返済する財政能力を持っていても、選択的に債務不履行に陥る可能性がある(実際にそうなることもある)。(Standard and Poor's 2007, 1, 3-4)。』

MMTは、貨幣的主権を持つ政府が、経済的・政治的な理由で進んで通貨の不履行を行うことができるという点に同意している。Cantor and Parker (1995)は、自国通貨建ての債務不履行に陥った政府の例を挙げ、「自国通貨建ての債務不履行は、通常、ロシアやベトナムのような古い政治秩序の転覆や、アルゼンチンやブラジルのようなハイパーインフレの抑制を目的とした劇的な経済調整プログラムの副産物である」と指摘している(Cantor and Parker 1995, 3)。しかし、CantorとParkerは、この種のデフォルトはまれであるとも述べている。仮に貨幣主権政府のデフォルト確率を見積もるとすれば、過去のAAA社債の5年間のデフォルト確率の中央値である0.02%よりもはるかに低い値になるだろう。これは、MMTが主張しているように、無意味と思われるほど低いものであると言えるであろう17。

pp.41

Defaults for technical reasons may also have occurred but these are irrelevant because they are resolved quickly. Venezuela is counted by Moody’s as having defaulted because “the person who was supposed to sign the checks was unavailable at the time” (Moody’s 2003; 22). The U.S. also defaulted in 1979 due to “unanticipated failure of word processing equipment used to prepare check schedules” (Zivney and Marcus 1989). We would not count that as evidence that MMT is wrong.

拙訳:

技術的な理由によるデフォルトも発生するかもしれないが、これらはすぐに解決されるので意味がない。ムーディーズでは、ベネズエラは「小切手に署名するはずだった人がその時にはいなかった」という理由でデフォルトになったとカウントされている(Moody's 2003; 22)。米国も1979年に「小切手の予定表を作成するためのワープロ機器の予期せぬ故障」が原因でデフォルトに陥っている(Zivney and Marcus 1989)。我々は、これをMMTが間違っているという証拠とは見做さない。

小規模開放経済における政策スペース制約の問題……固定為替、通貨ボード、ドル化

pp.43-44

In the worst case, some countries have limited real and external financial resources so their policy space is highly constrained as unskilled labor and unproductive land are the only resources they may have, and their government currency might not be accepted externally. In that case, foreign aid is crucial but some improvements can be made by using the labor force for specific public purposes that require limited external physical and financial resources. Payments in kind may also be necessary (to make sure to create a demand for the domestic production and to avoid imports of foreign products that are similar). In the most favorable case, a country provides the international currency and the rest of the world desires to save the international reserve currency. In that case, desired net saving by foreigners is positive because they want to accumulate net worth beyond physical accumulation, and so a current account deficit by the country supplying the reserve currency is needed.

Open economies are more sensitive to fluctuations in exchange rates and may desire to curb exchange-rate fluctuations by pegging a currency. MMT notes that there are different degrees in this type of policy that influence the policy space available to a government. A crawling peg provides some policy space that varies according to the exchange rate band. A currency board, the last step before completely giving up monetary sovereignty (“dollarization”), provides almost no policy space and so makes it difficult for a government to set its own policy agenda. Palley argues that dollarization contradicts MMT.

Small open economies with histories of high inflation have also shown themselves prone to the phenomenon of currency substitution or “dollarization” whereby domestic economic agents abandon the national money in favor of a more stable store of value. Dollarization shows that the store of value property is an important property of money, contrary to MMT denials of the significance of this property. (Palley 2013, 21)

This is a very strange claim by Palley; we know of no place where MMT denies the importance of stores of value, although like Keynes we wonder who would be sufficiently “insane” to hold cash balances if there are better alternatives. In addition, MMT does recognize that some small open economies may benefit from dollarization given that almost none of their economic activity is driven by the domestic private sector and government spending. MMT just states that the demand for the government currency is determined at minimum by the tax levy and the capacity to enforce it. In a highly open economy, residents may not use the government currency for purposes other than making legal payments to the government (“taxes”). If the government has limited means to enforce legal payments, the demand for the currency will be even smaller and so the capacity to spend without generating inflationary pressures will be even more limited.

Assuming that tax enforcement is perfect and that government currency is only demanded for tax purposes, then the equilibrium for the government will be a balanced budget. In that case, the equilibrium external balance will be determined by the desired net saving of foreign currency by the domestic private sector. Achieving that desire, however, is much harder than in the case of a monetarily sovereign government, because domestic private economic units have to rely on the desires of foreigners, and domestic economic units have limited capacity to influence this. The desired net saving of the domestic private sector and the foreign sector may not be compatible, which could lead to a painful adjustment process.

拙訳:

最悪の場合、一部の国では、実物的資源および対外的財源が限られている場合、政策スペースが非常に制約される: 非熟練労働者と非生産的な土地しか資源がなく、また政府通貨が対外的に通用しない可能性があるためだ。このような場合、外国からの援助が不可欠となるが、外部の物理的・財政的資源をあまり必要としない特定の公共目的のために労働力を利用することで、ある程度の改善が可能である。また、現物支給が必要な場合もありうる(国内生産物の需要を確実に生み出し、類似した外国製品の輸入を避けるため)。最も好ましいケースは、ある国が国際通貨を提供し、世界の他の国々が国際基軸通貨の貯蓄を望む場合である。この場合、外国人が望む純貯蓄は、物理的な蓄積を超えた純資産の蓄積を望むためプラスとなり、基軸通貨を供給する国による経常収支赤字が必要となる。

開放経済国は為替レートの変動に敏感であり、通貨を固定することで為替レートの変動を抑制したいと考えることがある。MMTでは、このような政策には程度の差があり、政府が利用できる政策スペースに影響を与えるとしている。クローリング・ペッグは、為替レートのバンドに応じて、ある程度の政策スペースを提供する。通貨ボードは、通貨主権を完全に放棄する(「ドル化」)前の最後のステップであり、政策スペースがほとんどないため、政府が独自の政策課題を設定することは困難である。Palley氏は、ドル化はMMTと矛盾すると主張している。