Why I Believe We Are Witnessing the Collapse of Our Healthcare System in Real Time

And What We Can Do About It?

Many hospitals have started putting beds in the hallways of their emergency rooms to increase capacity.

This month marks my ninth year as a nurse. In the past nine years, I have personally watched the healthcare situation in the United States go from bad to worse. Every year we seem to have more problems than the last and more challenges to work against. Ultimately, it’s our patients that suffer from lower quality care and longer wait times.

The chief problem with the U.S. healthcare system has historically been the exorbitant cost. The U.S. sticks out like a sore thumb when it comes to spending on healthcare for a comparable number of doctors, nurses, and hospital beds, according to data from OECD.

More recently, however, access to healthcare is becoming a larger problem than the cost. In the last few years, hospitals have faced unprecedented overcrowding of their emergency departments and inpatient units resulting in ambulance diversions, increased wait times to be seen, increased time it takes to be admitted to a bed upstairs (also known as ER boarding), and a doubling in the number of people who leave the hospital without being seen (LWBS) due to the long wait times. The American Medical Association has called out these problems in recent studies.

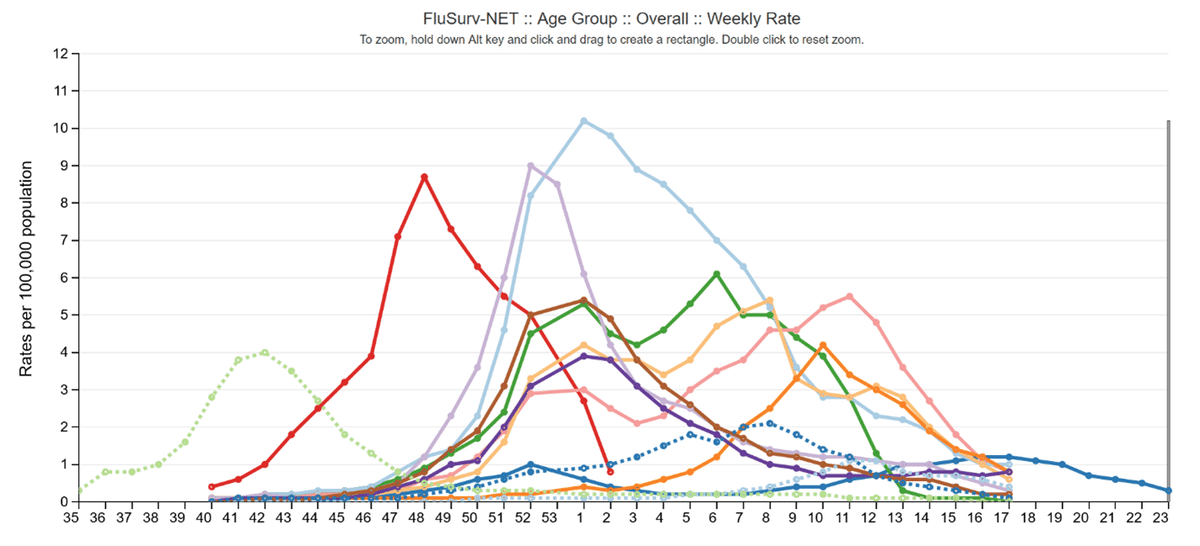

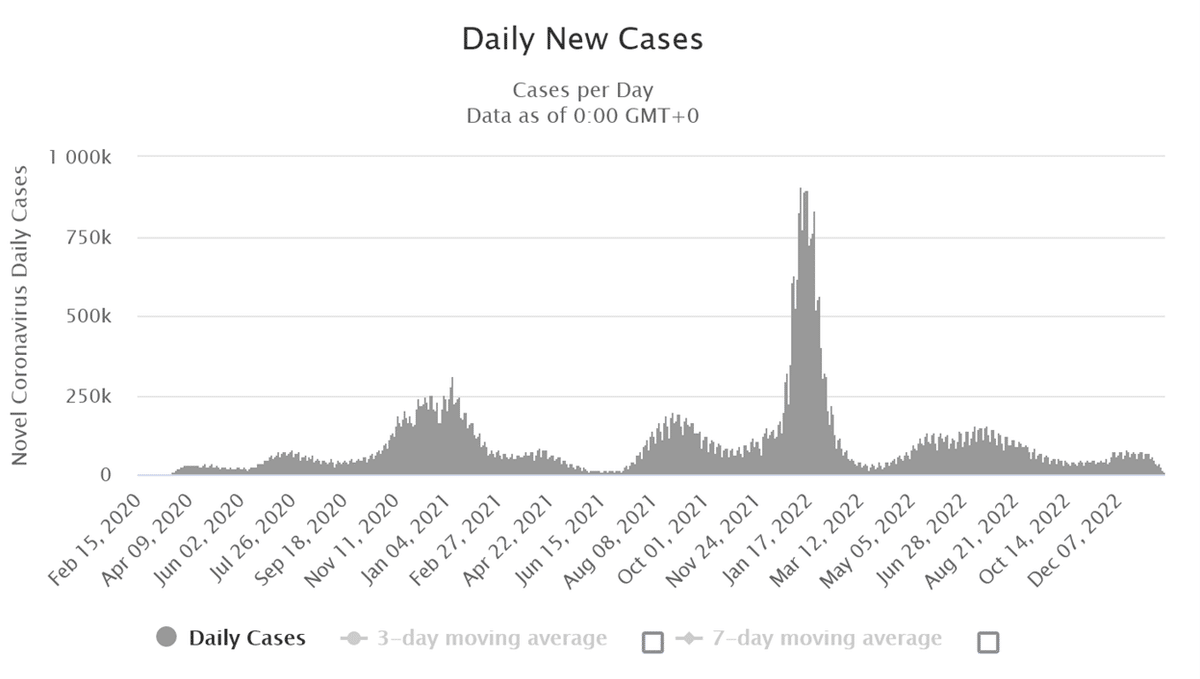

One possible explanation is what Yale has termed a “tripledemic”. In 2022 and 2023 there was a bad mix of influenza (flu), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and Covid-19. While I agree that seasonal increases in respiratory illnesses acutely exacerbate an already over capacity system, I feel that relying on this explanation alone misses what I believe to be much larger structural problems in the healthcare system that are not just present in the U.S.

Wait time to access healthcare is not just a U.S. problem and is much worse outside the U.S.

A 50 hour wait to be seen by a doctor in the emergency department or a multi-day wait to be admitted to an inpatient bed in the U.S. might seem like a long time, but this pales in comparison to wait times for “non-urgent” care in socialized healthcare systems such as in the United Kingdom or Canada. According to data from the U.K.’s National Health Service, millions of people waited 18 weeks or more, some more than an entire year, to access healthcare which includes referrals to specialists (consultants), testing, and treatment. The trend of people waiting up to 18 weeks for care was steadily rising even before the nurse and ambulance driver pay strikes in late 2022. Canada has a similar problem. According to data from the Fraser Institute, the average wait time was 27 weeks in 2022, a threefold increase since 1993.

An aging population will only worsen the problem

In a prior Note, Why The United States Is Currently Like Japan In The Year 1995, I went into detail about how the U.S. may experience a population demographic shift similar to what Japan is currently experiencing. In short, a declining birth rate in Japan beginning in 1974 caused Japan’s population to peak in 2010. The population has been declining since and is getting older. Japan now has the oldest population in the world with a median age of almost 50 years old, meaning half the population is 50 or older. In the U.S., the birth rate began declining in 2009 and the U.S. population may subsequently peak in 2045 and begin declining in a similar way to what is occurring in Japan.

Modern healthcare allows us to live longer lives, but as more people become older a greater number will need doctors, nurses, and hospital beds. The system is already at, and in many cases over, capacity with the current population. I fear a true crisis is on the horizon as the U.S. population ages and more people need access to a limited supply of healthcare services.

Alarming evidence of the negative impact of an inadequate healthcare system is already starting to appear. Life expectancy has declined in the U.S. for two years in a row now from 78.8 years in 2019 to 77.0 in 2020 and down to 76.1 years in 2021. The Covid-19 pandemic precipitated this decline, but I worry that the current strains on the healthcare system will prevent this downward trend from reversing if people are unable to access the care they need in a timely manner.

Increasing the supply of healthcare may not be the solution

The knee jerk reaction to this looming healthcare crisis is a call for more funding, more doctors, more nurses, and more hospital beds. The U.S. already spent $4.1 trillion Dollars, or 17.8% of its GDP on healthcare in 2021. Thus, I'm not sure that throwing more money at the problem is the solution. Fortunately, Japan may offer insight that further increasing the healthcare supply may not be the answer. According to OECD, Japan and the U.S. have a comparable number of doctors and nurses, but Japan has a higher life expectancy than the U.S. at almost 85 years compared to the U.S.'s 76 years. Japan also spends only 11.1% of it's gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare compared to the U.S.'s 17.8% expenditure. Japan is caring for a population that is much older than the U.S. too. There is variance in the number of hospital beds Japan has, but this may be due to how Japan classifies a “hospital” bed which also includes long-term stays comparable to a skilled nursing or rehabilitation facility in the U.S. that isn't included in U.S. acute hospital bed data. This variance is also observed in hospital length of stay which is 16.4 days in Japan versus 5.4 days in the U.S.

So what is the answer?

How does Japan deliver better results (higher life expectancy) at lower cost and with a comparable number of healthcare team members? Data from the OECD offers some insight. Japan has the lowest overweight and obesity rate in the world. The U.S. is in second place for the highest rate of obesity at an astonishing near 75% of the population!

Obesity and being overweight is associated with high blood pressure and diabetes which increases the risk of heart disease and stroke. These conditions require treatment by a healthcare professional and often at some point in a hospital setting. If these conditions progress, the chronic problems like heart failure or disability from stroke can necessitate dependence on healthcare such as multiple hospitalizations or nursing home care. The loss of personal independence is one negative connotation, but the demand on the healthcare system which exceeds the available supply lowers the quality for everyone. There are 271 million people in the U.S. 15 years old and older. If 75% of those people are obese or overweight that is 204 million people at risk for needing access to healthcare to manage their lower quality health.

We have to reduce the demand on the healthcare system

Barring a revolution in android doctors or nurses or a MedPod or Med-Bay from the Prometheus or Elysium movies, our supply of healthcare is likely to remain inflexible. The supply may even shrink in the coming years as current and future healthcare team members are dissuaded from the profession due to exhaustion or low pay. The Covid-19 pandemic gave many healthcare workers cause to either retire or quit the field. Thus, the only lever we may be able to manipulate is the demand side of the equation. The only way to reduce the demand for healthcare is to individually strive to live healthier lives and ideally not need the emergency room or hospital except for true medical emergencies. Some ways to help improve health and reduce the risk of future health problems is to:

Maintain a healthy weight

Eat less and move more

Do not smoke or use drugs

Do not drink excess alcohol

Get routine physicals at a primary care or family doctor and monitor for conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol and get treatment if you have them

Limit salty, sugary, and fatty foods and drinks

I feel that if we continue down the current path of inactivity and poor diet and then expect the healthcare system to just be ready and waiting to undo a lifetime of unhealthy habits in one ER visit or a five day hospital stay, we are setting ourselves up for a very bleak future of more hospital overcrowding, longer wait times, lower quality and delayed care, and lower life expectancy as a result of that lower quality and delayed healthcare.

We must begin to accept some personal responsibility to better our health and reduce the rates of obesity and being overweight so we ideally don't get sick as often and need to rely on the over capacity healthcare system. If we don't, well, we're already seeing the consequences in the news of people dying waiting to get into a hospital that has no bed for them.

What route to take will ultimately be a personal choice.