A personal history of interactive installations - Part 1

Preface

This article is part of Takram's "Mark @ Design Engineering" research group activities, in which we may experiment with new technologies or write articles to research topics of interest.

In this article, I will present Part 1 of a personal history of interactive installations. What that means is that rather than aiming for an exhaustive history of the field, I'll be featuring the key moments and figures that stick in my mind, had an impact on me and which form my basis for understanding the field as it is practiced today in design intervention (as I do at Takram).

Being from North America, I felt it would be a fun exercise to present my mental model of the field and see if I can get some feedback about how it compares with that of people who learned and have been practising it in Japan (like my colleagues). As such, feel free to comment if you think there are some seminal Japan-related moments or figures that you think ought to be included.

This "Part 1" specifically focuses on The Past, therefor I plan on writing follow-up articles on The Present and The Future of interactive installations.

1.1) A Definition

First of all, what exactly is an "interactive installation"?

My definition is: a physical installation that can be interacted with by the audience. Technologically-speaking, the installation can be either analog or digital, or both.

An analog installation by La Camaraderie . People add their drawings to a zeotrope to create a collaborative animation.

A digital installation by teamLab . The contents are digital and the user interaction (ie. Motion tracking) is indirect and computer-controlled.

1.2) Early Origins

We could say that the first examples of people using tools or interacting with physical items for the purpose of entertainment / education could be from toys or from the theater. Toys might be a more obvious ancestor to today's interactive installations, but the theater does present a For example, the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk (ie. The "total work of art", made famous by Richard Wagner in the mid-18th century as a core principle of his theatrical art) has left an indelible mark on the conceptual aspirations of most contemporary interactive installations, seeking to create an immersive and multisensory experience.

Toys and exhibition devices have a long history of being presented at world fairs and universal expositions. This praxinoscope was invented by Charles-Émile Reynaud and presented at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, 1878.

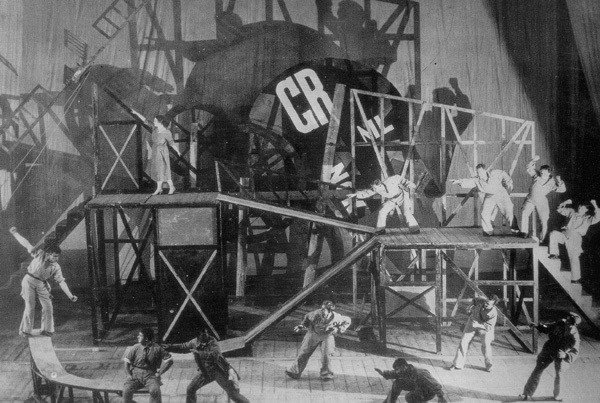

Russian Constructivist Theater provides some early precedents for using large mechanical installations in entertainment. This stage is for a play by Vsevolod Meyerhold, in 1922.

Wagner's ideal of a "total" (or completely immersive) artform is made apparent by his whole-ranging ideas on stage design, mechanical props, and even the architecture of the theater itself. One could say that the contemporary terms of "immersive" and "holistic" that are used ad nauseam in today's interactive / experiential design industry trace its origins back to this. (As a side note, the professor I had in university that introduced me to the historical importance of theater and performance in regards to modern interactive experience design actually wrote this book on the topic .)

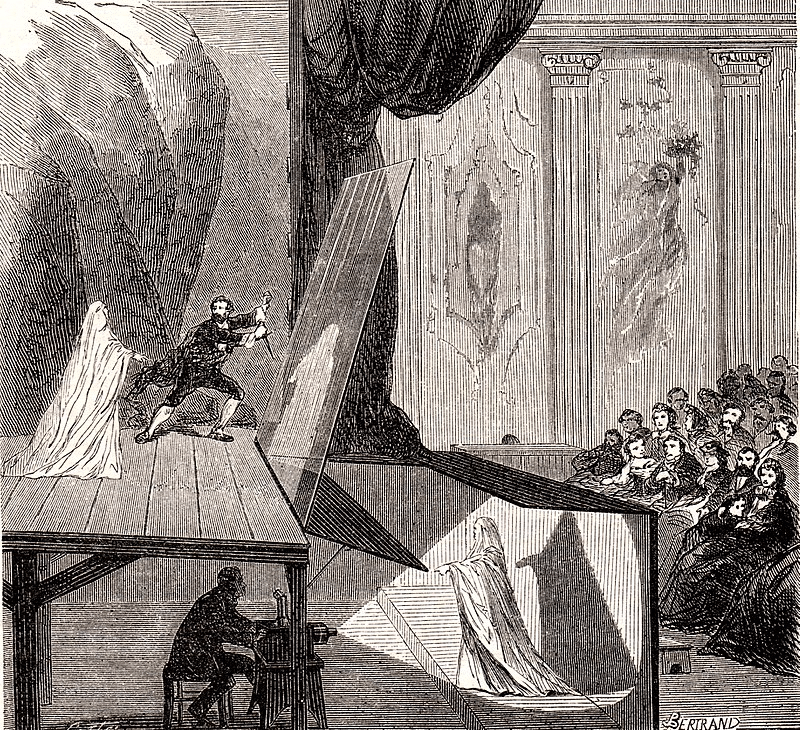

The Gesamtkunstwerk and the Bayreuth theater of Wagner introduced the pursuit of phantasmagoria; the creation of a inexplicable sense of immersion in the theater-going experience. Above, the illusion known as "Pepper's Ghost".

When I look at this new Disney ride, aiming to immerse the audience and remove the separation between it and the performance, I can't help but think of Wagner. All the choreographed combinations of machinery, projection and sound echo back to those early ideas . Perhaps the same could even be said about teamLab installations or AR / VR games, I wonder?

The Bauhaus school was another unmistakable influence on media art and, consequently, interactive installations. Of note was László Moholy-Nagy, a professor there who innovated in multiple mediums and who's ideas affected a wide range of disciplines, from video art to electroacoustics. His piece below is often considered as the first kinetic sculpture in modern art.

Light Prop for an Electric Stage, by Moholy-Nagy, 1930. Widely considered as the first kinetic sculpture in modern art.

A new documentary on the legacy of Moholy-Nagy, who's importance seems to have been rediscovered of late.

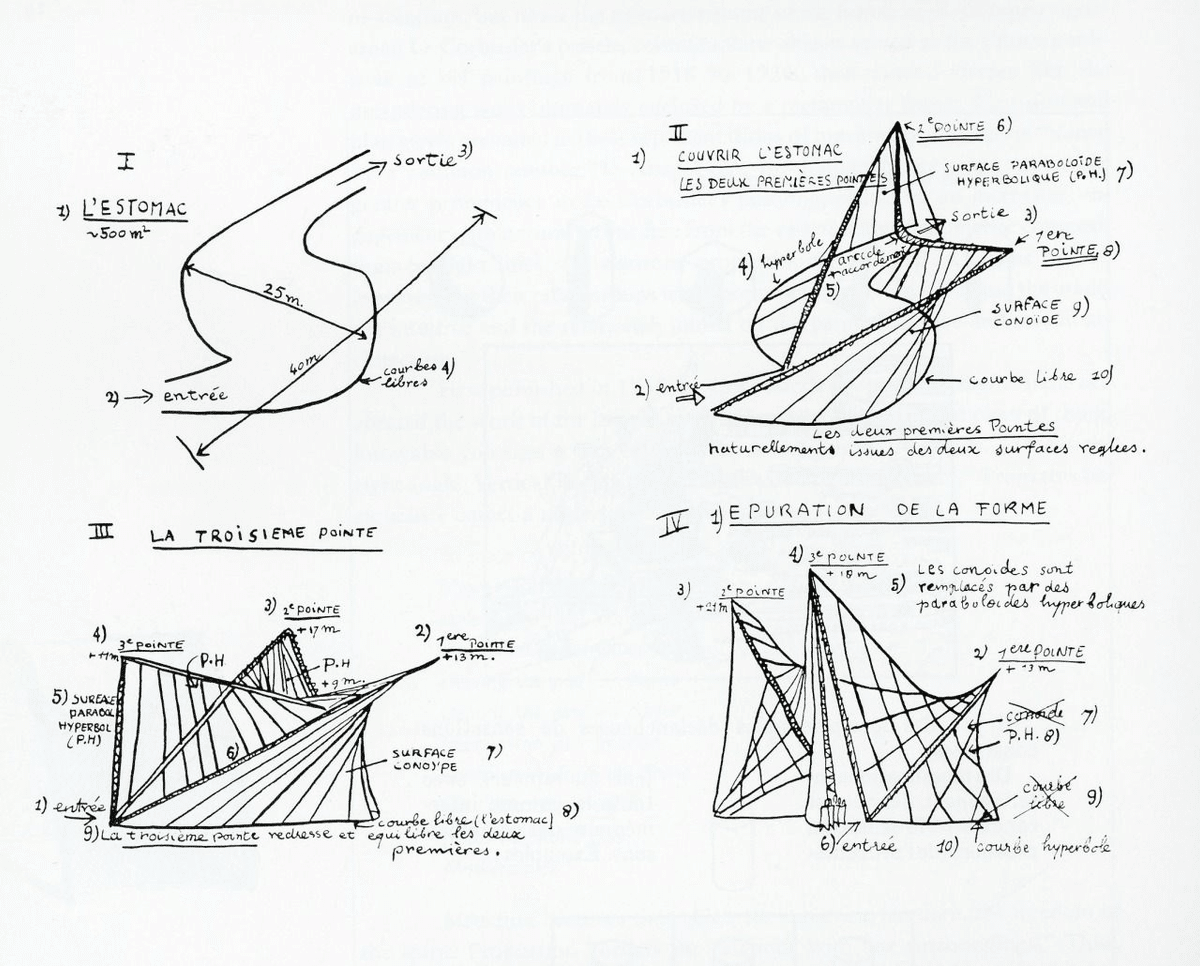

The effects of Moholy-Nagy (and his Bauhaus peers, undoubtedly) can be traced to the beginnings of electroacoustics, musique concrète, and the works of such notable figures are Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage. Another related figure in terms of interactive installations is Iannis Xenakis, architect and artist who's multi-medium approach to creating multi-sensory experiences were most notable for the time. In 1958 at the Brussels World Fair, Xenakis worked on 'Poème Électronique' (with Le Corbusier and Edgard Varèse), one of the first well-known examples of public multimedia art installations. It featured film, slides and lighting on the walls and ceiling inside a Le Corbusier-designed structure. It probably can't be considered to be an "interactive" installation, but it did have an evolving sound-path that was spatially-controlled by perforated control tape and human operators. Here is a good timeline of the history of computer music which mentions it and the above artists.

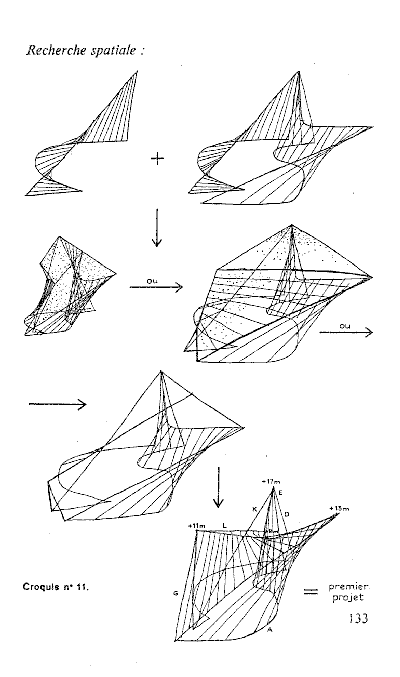

The Philips pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World Fair, inside which played Poème Électronique.

Above, some of Xenakis' sketches for the Philips pavilion.

A short documentary about the Poème Électronique project presented at the 1958 Brussels World Fair.

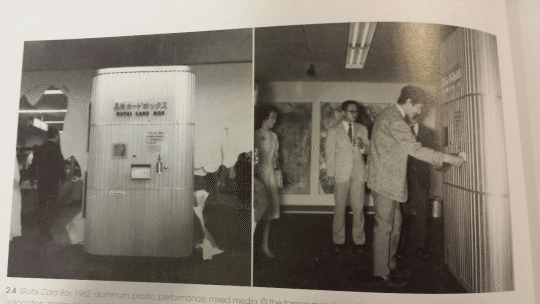

In Japan, the Gutai group paved the way for "interactive" installation art with works like Gutai Card Box (1962) in which the audience could order a painted postcard from the artist sitting inside a vending machine-like contraption. Although simple, the inclusion of the audience into the artwork can be seen as a precursor to modern interactive experiences centered around the audience or viewer.

Gutai Card Box (1962)

1.3) Birth of the Modern Computer

At first, interacting with computers was very limiting, where options simply went from punch cards to simple input/output devices like mice, screens, etc. Bell Labs, Xerox PARC, and other famous research facilities pioneered some of the most important breakthroughs.

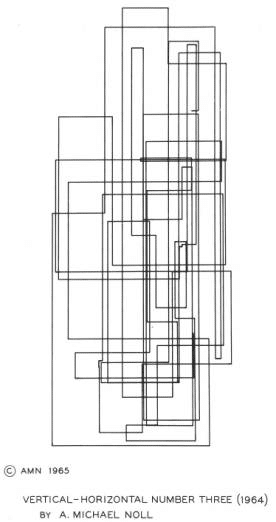

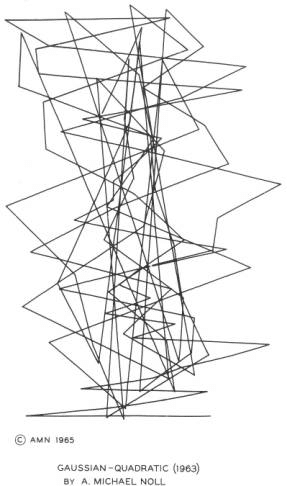

A. Michael Noll is said to have created the first digital computer art in 1962, while working at Bell Labs, and is also known for some of the first computer animations for TV and movies. Here is a history of early digital art at Bell Labs.

Bell Labs even housed a research program called 'Experiments in Art and Technology' (E.A.T) that brought together their technological innovations with artists. They produced many events that are considered the first large-scale collaborations between artists and research engineers, bringing forth the dawn of technologically-enabled, interactive, and even participative art installations (eg. 9 Evenings).

Ivan Sutherland's Sketchpad demo, 1962, influenced much work done afterwards at Xerox PARC, and later influencing Apple. Another famous demo that also had a huge impact on PARC was the 'Mother of all demos' by Doug Engelbart, in 1968.

Decades later, as computer technology jumped forward, digital computer animation suddenly started to appear in the mainstream. People like Loren Carpenter and Alvy Ray Smith, who eventually became co-founders of Pixar, created some of the earliest examples.

Loren Carpenter is credited with the first fully-computer-generated 3D graphics in 1980 with 'Vol Libre'. Fractals were used to generate the terrain. This led Carpenter to create the first 3D graphics in mainstream movies for the terraforming sequence in Star Trek II - Wrath of Khan (1982) (below).

The famous terraforming sequence in Star Trek II - Wrath of Khan (1982), by Loren Carpenter.

1.4) Keyword: Immersion

It would be difficult to talk about interactive installations in entertainment without including at least a little about Disney. Since the 1950s, the Walt Disney Imagineering group has built some of the world's most popular installations featuring mechatronics, robotics, etc. As far as recent design industry trends or buzzwords are concerned, I wouldn't think it is a stretch to say that many of them might originally have come from Disney (eg. immersion, storytelling, "immersive storytelling", "immersive environments", etc.).

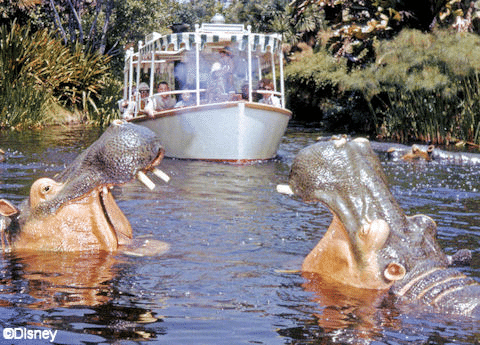

"When Disneyland opened in 1955, the park featured crude versions of AudioAnimatronics (AA) figures. These figures had limited movements and were unreliable. This is best illustrated by the simplistic animals seen on the Jungle Cruise." (source)

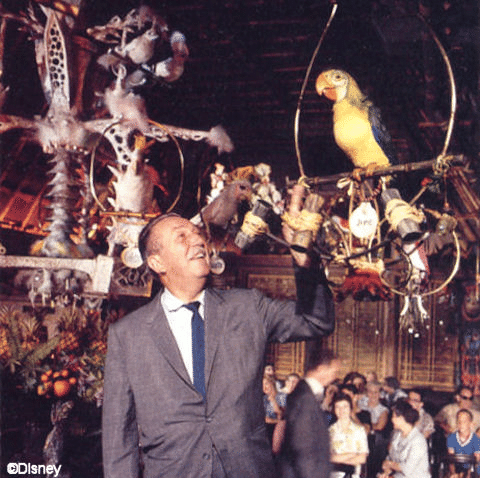

"Walt Disney’s Enchanted Tiki Room" opened in 1963 and featured various robotic singing performers such as birds and flowers. "The show contained 225 AA performers directed by a fourteen-channel magnetic tape feeding 100 speakers and controlling 438 separate actions." It was so advanced for it's time that guests just didn't "get it". (source)

"The exploration of space brought a number of technological advancements to the world in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Disney Imagineers were able to capitalize on these inventions and apply them to their crude figures. With the use of rudimentary computers and new hydraulic and pneumatic hardware, their animals began to move less like robots and more like the real thing." (source)

Thanks to all the technical innovations during that time (like at Bell Labs and Xerox PARC), inventors kept trying to increase the audience's sense of immersion using computers. See here for a nice timeline of the history of VR.

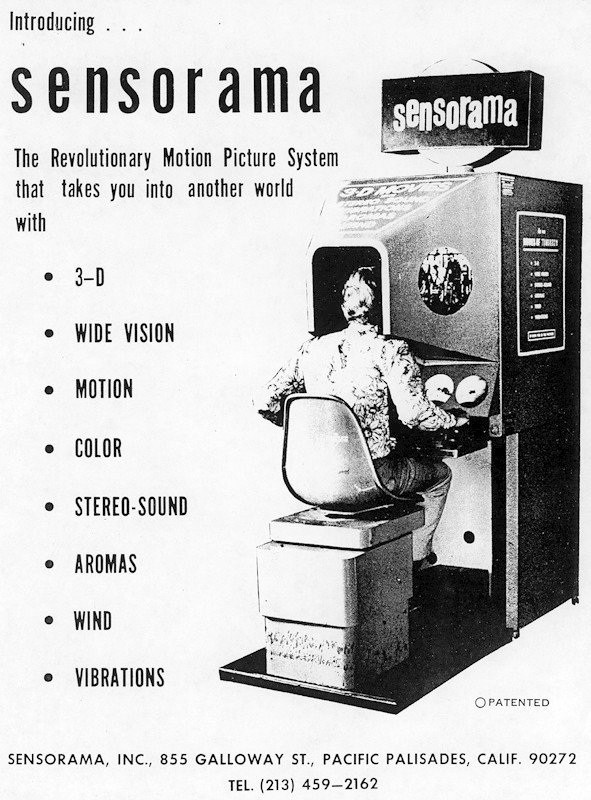

Cinematographer Morton Heilig created the Sensorama, the first VR machine (patented in 1962) that tried to stimulate all of the senses using color 3D video, audio, vibrations, smell and wind.

1.5) From Passive to Interactive

From the 1960s onwards, it seems that two important things started to change: installation art was discovering the concept of being "interactive" (even without technology), and digital technology was seeping into various artforms (theatre, film, etc.) while just beginning to hint at it's potential for interactivity.

Without mentioning too many analog (ie. pre-digital) installation artists, below are two notable ones that helped give rise to interactive experiences.

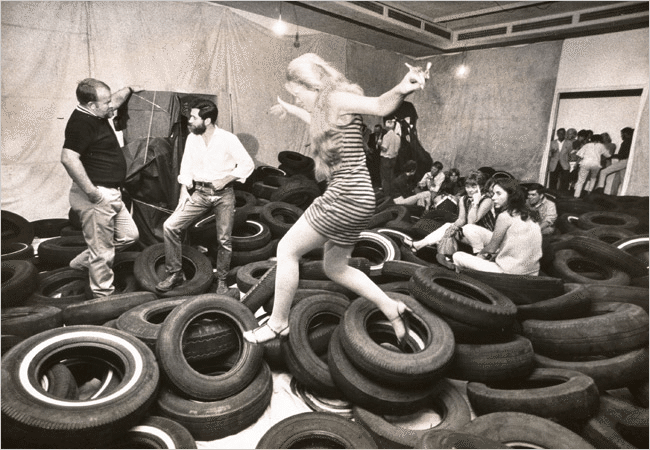

Yard, by Allan Kaprow, 1961. Tires are left in a space with the audience forced to traverse them while being encouraged to move the tires as desired.

Words, by Allan Kaprow, 1962. The audience is encouraged to contribute to written and verbal components as they progress through the artpiece. Kaprow's works are noted as some of the earliest examples of actively including audience participation into the artwork, leading to the concept of "interaction" and interactive experiences.

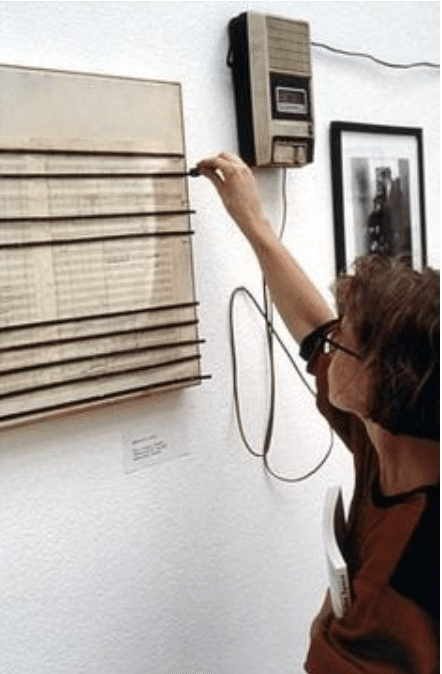

Random Access Music, by Nam June Paik , 1963. "In this piece, the audience is able to create [their] own sound collages. [...] Paik's main goal in Random Access was to disrupt the passive role of the recipient. [...] The recipient has the opportunity to become a creator by himself "( source )

In the world of theater and performance, creators were now armed with new technical possibilities. Although the theater is not usually interactive (after all, the audience is traditionally kept separate from the action) these new digitally-enabled creations were spelling-out the future possibilities of experiences in which the audience could also soon take part (and not just the performers). As such, the idea of the gesamtkunstwerk makes a resurgence in a quest to create a complete immersion of the senses.

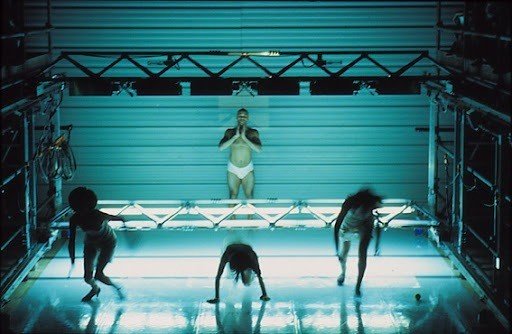

Needles and Opium, by Robert Lepage , 1991. A Canadian scenographer and theater producer renown since the 1980s for innovative stage designs that simultaneously disorient and immerse the audience. Also, on Youtube .

pH, by DUMB TYPE , 1990. Pioneers of multimedia theater and performance, their influence has been felt in almost all facets of interactive art, especially in the installations of ex-member Ryoji Ikeda .

Studio Azzurro , early pioneer of immersive video installations, created experiences that felt interactive & immersive by careful content choreography, even though the pieces didn't always include interactive systems.

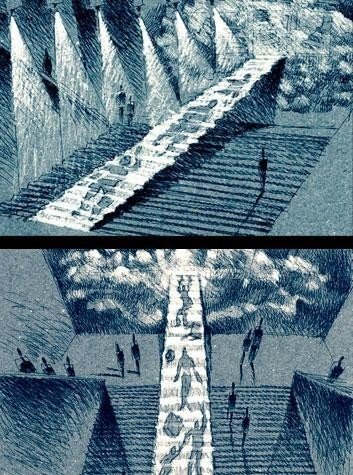

Studio Azzurro, La Citta degli Occhi , 2002. This piece is actually interactive, as the projected characters on the stairway react to the audience which can also climb the stairs.

With the democratization of new technologies, interactivity quickly became the trendy, shiny new toy that many artists wanted to play with, infiltrating all art-related disciplines, from installation art to architecture. Whereas today, it has become a practically essential component of any experience offered by a commercial design agency.

Blur Building , by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, 2002. "Interactive" is not always in respect to the audience; in this case, the piece reacts to climatic conditions in order to regulate water pressure, etc. Another interesting element of the piece was its critical stance vis-à-vis the design / art industry at the time: "Contrary to immersive environments that strive for visual fidelity in high-definition with ever-greater technical virtuosity, Blur is decidedly low-definition." Undeniably influenced by Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya .

Towards "Part 2-The Present"

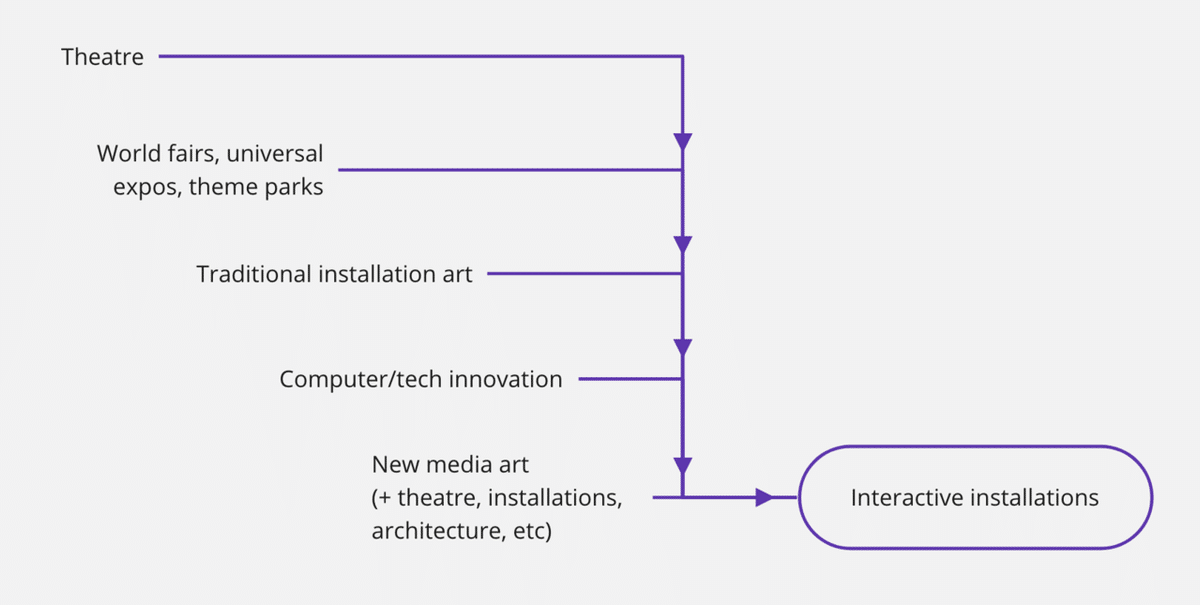

As I see it, "interactive installations" come from the addition of tech innovation to traditional / analog installation art (which itself has the lineage described above).

In the next part, we'll dive deeper into what trends, movements, or artists I especially think of when considering the present state of interactive installations. I imagine it will probably cover the 2000s up to present day.

And after that, towards the Future (... Part 3)!