ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #2_Design Development |Prototyping and Updating the Hypothesis

In December 2019, NKC Nakanishi Metal Works Co., Ltd. (referred to as NKC in the following) launched their new whiteboard, “ideaboard®.” Unraveled by the project members themselves, this series records the story of how the ideaboard was brought to life, and into ours.

《Past articles》

ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #1_ The Idea|On Persistently Nurturing a Seed Idea

The series continues with Riku Nagasaki, head of “KAIMEN” (the business design team reporting directly to the president at NKC) as he lets us in on the process of realizing ideas.

Riku Nagasaki

head of KAIMEN

NKC BUSINESS DESIGN CENTER

1. Developing business through design: KAIMEN’s first project

—To begin with, what kind of department is KAIMEN?

It all started when we were approached to build an in-house design department.

However, I already thought that the in-house design business model was reaching its limit. If we were to truly take on “design management,” we would have to follow the process of shaping new ideas with designers taking the lead and submitting it for public evaluation. This is what is referred to as “design-driven innovation” as well. I told them that if they really wanted to do this, they would have to join me on my ideas on how this department should be. As a result, with a three-year time limit, we were able to launch “KAIMEN,” a department where businesses would be developed through design.

—When was it that KAIMEN began to take on the project of ideaboard?

KAIMEN was just me for the first half of the year. I was tackling lonely tasks such as searching for members or building the office. "Ideaboard" was the most realistic thing that came to mind when I thought of what I could specifically start doing by myself.

2. The creation and accumulation of great mistakes

—How did you shape the ideas built in your mind?

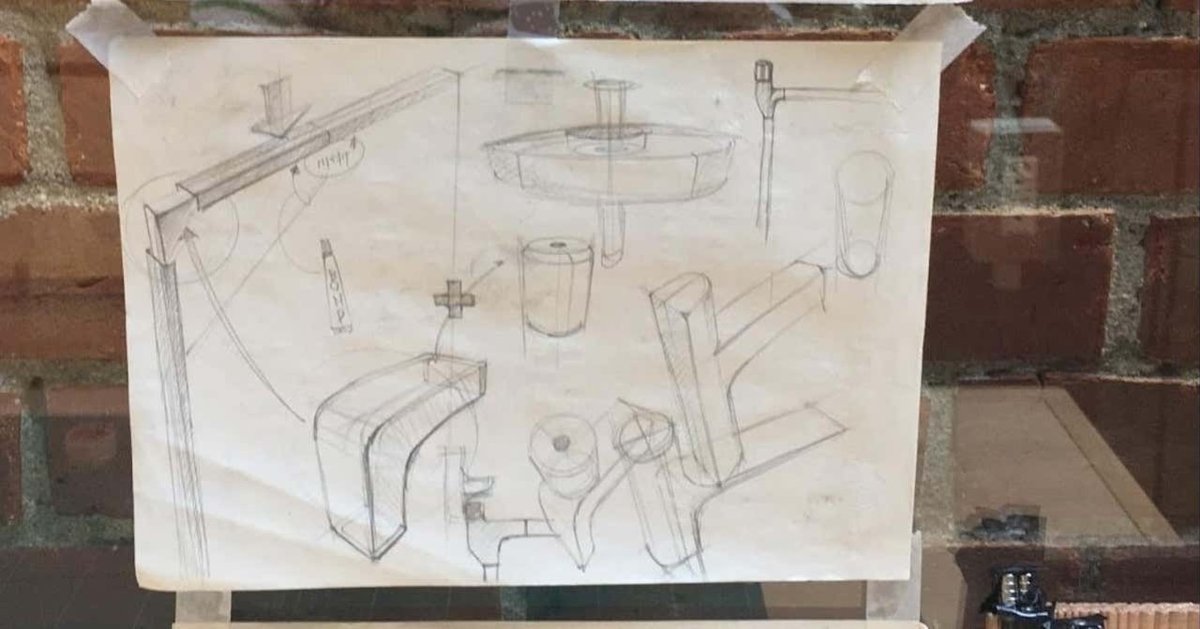

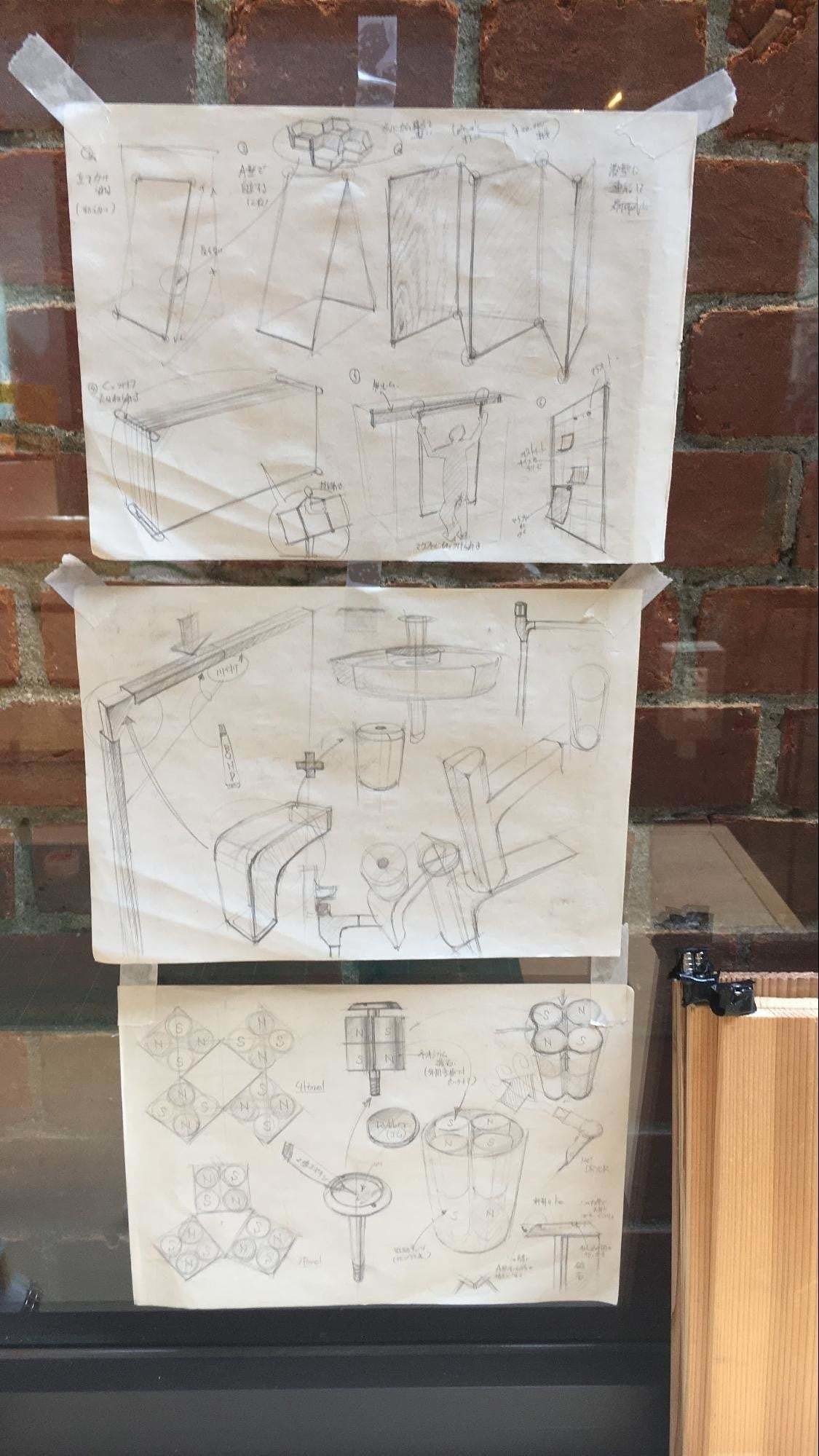

This is the first sketch. I was thinking as I randomly drew sketches.

How can I prevent it from bending backward? How can I combine two together? How about using a honeycomb structure for the inside to make it lighter? Maybe the boards could click together when connected or stacked up? Perhaps one could carry five boards by fastening a belt around them? I was creating one idea after the other.

Furthermore, being a big fan of physics and science, the issue of structure also often comes to mind. For instance, I would think of something like: if we were to freely spin numerous multipole magnets on their axes, the S pole and N pole would automatically turn so that the magnets would line up side by side, regardless of whether there were an even/odd number of magnets. I quickly became interested in trying it out, so I bought a neodymium magnet at a hundred-yen shop and experimented right away. What I created based on this experiment was what became the first prototype.

—You immediately started making.

For KAIMEN, “making” is the most important matter. Before anything, make. Shape the idea into something you can show. This is basically KAIMEN’s meaning of existence. We make tons of stuff.

Although the quality has improved as we’ve become used to the process, making mistakes is more important than anything. It’s actually hard when we don’t fail, and it is these cases that we often end up questioning the project’s certainty. This early prototype actually also turns out to be a failure later on.

—How about market research?

To begin with, I don’t believe in market research, and when you are particularly making something that doesn’t exist, no one can judge what is good or bad. In that sense, we don’t do any kind of plain market research.

What we do emphasize is observing how each person uses existing products or prototypes. Things like, sensing someone’s confusion, or noticing when someone seems uncertain on how to place a product upright. You come to understand these things when you are patiently observing the user.

3. Verifying the hypothesis of “flexibly assemblable”

—Even at this stage, were you observing the user’s way of handling the product?

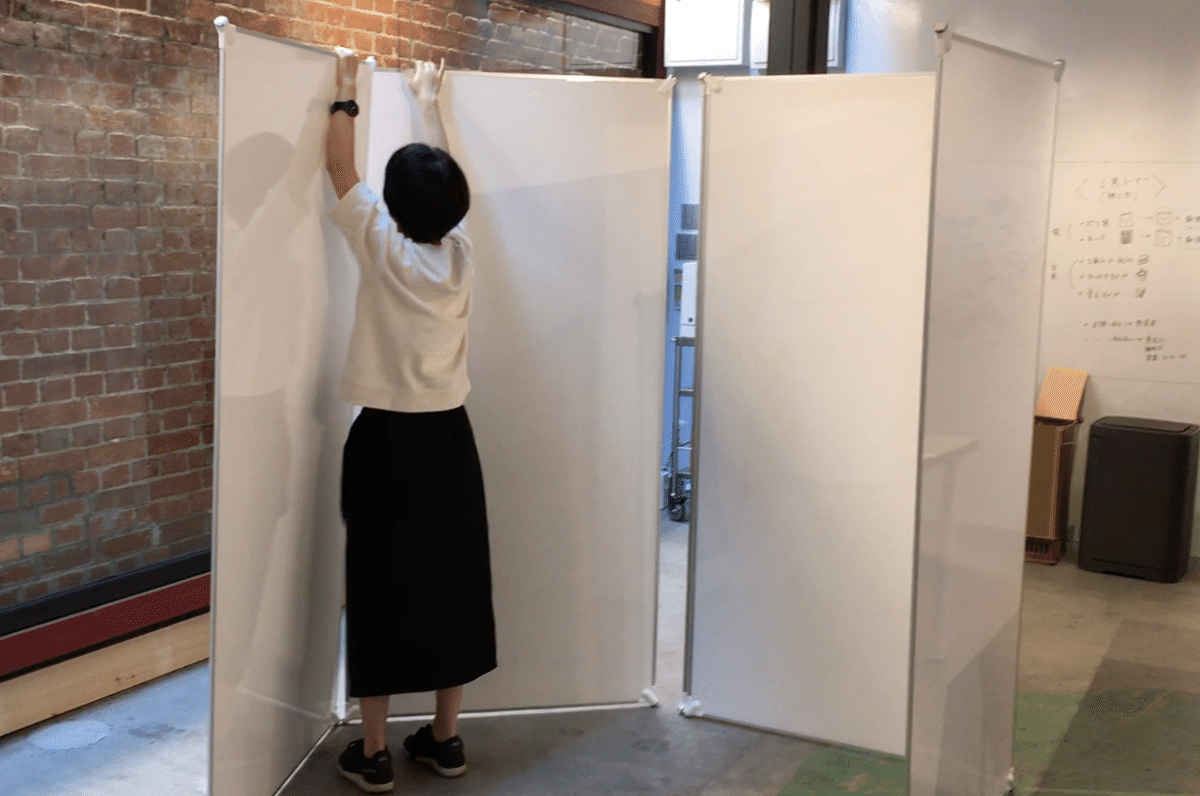

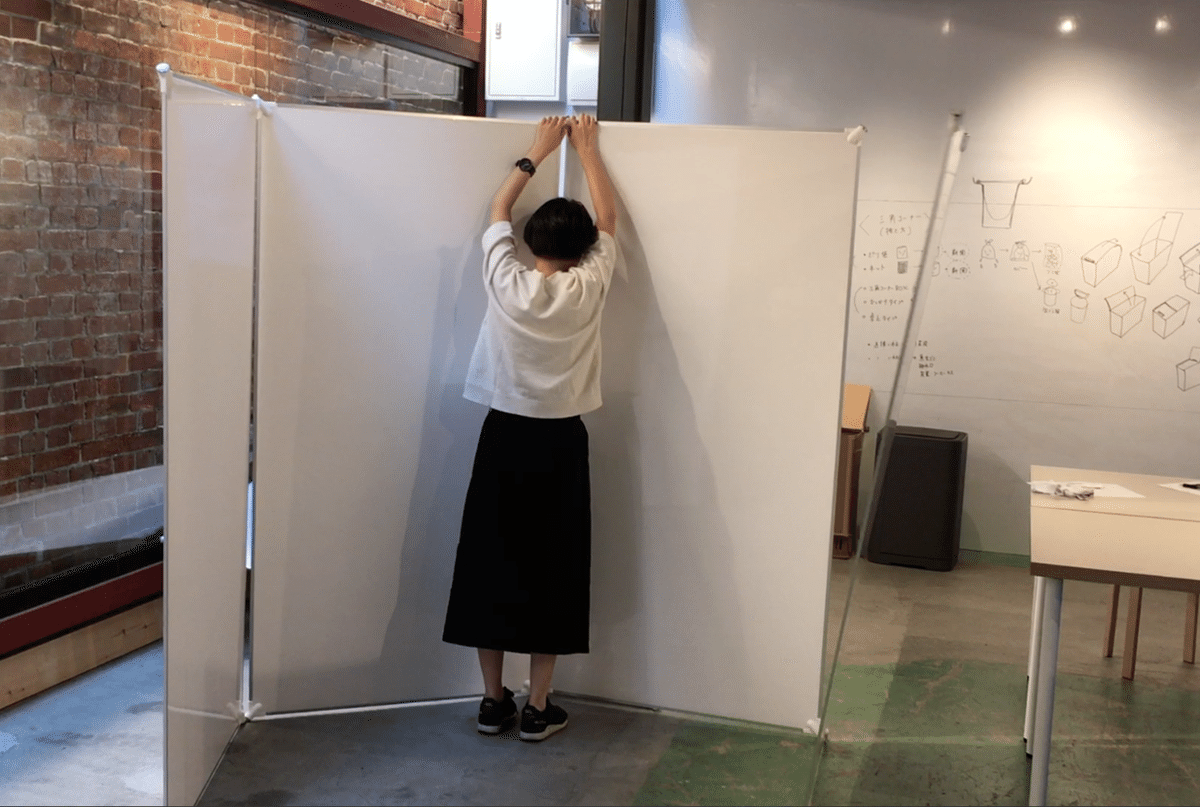

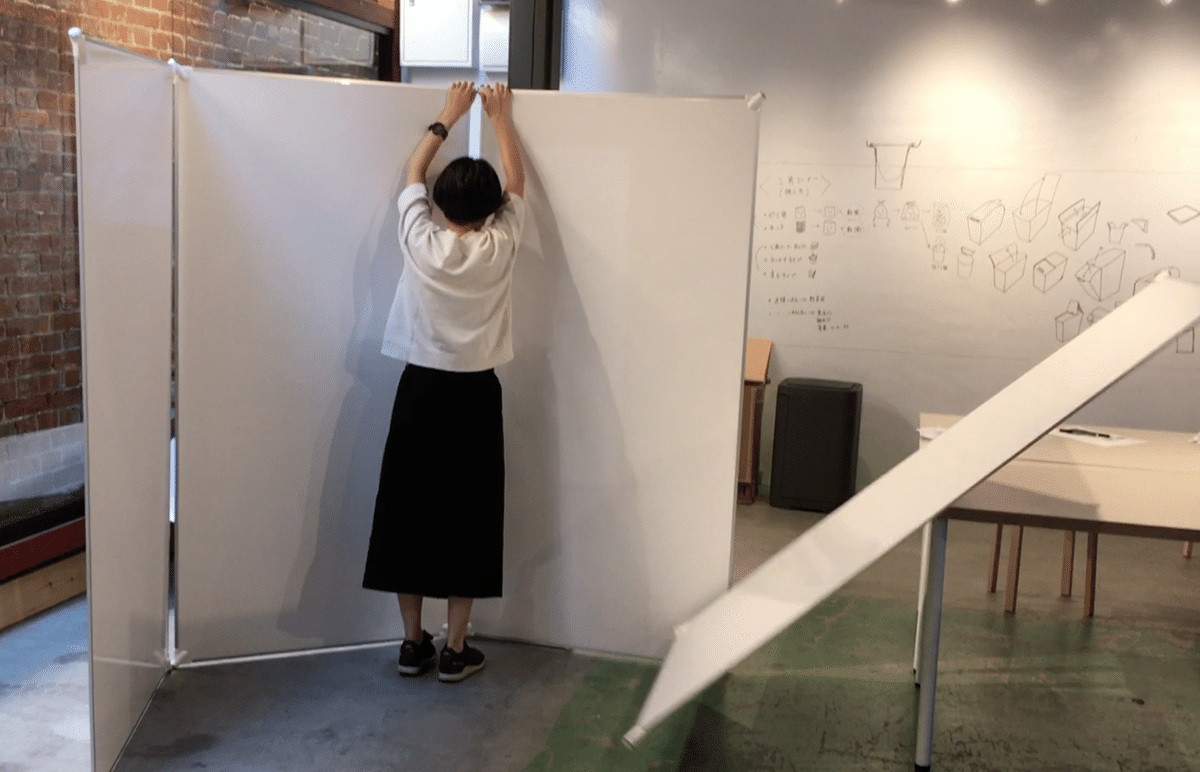

After the prototype took shape to a certain degree, we packed five boards and sent it to MTRL KYOTO whom we were communicating with daily at the time. We had come to the idea on our own that they would use the prototypes in creative ways, such as placing them in their open spaces at the Fab Cafe on their first floor.

However, this turned out to be a total failure on our end, as they didn’t use them as we expected at all. The assumption was completely wrong. There were two reasons: one coming from functional aspects and the other from the user’s experience.

The first problem occurred when the user would lay the connected boards on the floor. Although seeming flat, there is usually at least an unevenness of 10-20mm to a floor’s surface—an unevenness that the magnets connecting the boards cannot withhold. If one part disconnects, the whole thing would fall apart. The user gives up. This was the reason with regard to the functional aspect.

In addition, the fact that many users would individually use a single board for themselves was unexpected. Some would stick the board inside the gap between their desk and the desk next to them, and use it as their personal whiteboard/partition. Others would tape the board in front of their desks.

Occasionally, there would be people who would use two boards, but since they couldn’t rely on the magnets’ connectivity, they would end up wrapping it with tape to secure the boards together.

Moreover, not once were two boards attached and positioned in the A shape so the product could stand on its own. We acknowledged that our initial hypothesis, that "the boards could be flexibly assembled," was a misconception.

4. Breaking down fixed notions through observations of real users

—It takes courage to throw away a hypothesis that you’ve put so much effort in and move on to the next.

We are humans ourselves, so we can never escape the bias, prejudice, stereotypes that we carry. It’s about the methodology to systematically break down these fixed notions.

First, you attempt to create a prototype from a hypothesis that you think is right and throw that at someone or your surroundings. Afterward, you then realize that the hypothesis was wrong, but can be dealt with a different method. I believe that is the moment when you are released from one of your biased ideas.

I think designers with some degree of training have a richer imagination than others.

They have the ability to find a stone that someone could trip on, and remove it, just a little before others can. That’s why they can imagine the shape of a button that’s easy to use, the way to use something without making an error, how to not get hurt, the problems that could happen during manufacturing.

However, nowadays, social environment/issues are becoming more and more complex, and solely relying on the imagination of designers is just not enough to solve these problems.

How we can complement this, is to have real people in real society use the products. It’s the process of observing the bugs and errors that occur, and updating our hypothesis.

In order to go through this repetitive process, we later distributed the boards to various design agencies, beginning with MTRL KYOTO.

—I feel it is extremely difficult to find the discomfort and needs which the users themselves aren’t yet aware of, just from observation.

My hobby is to gather “user’s out-of-purpose usages.” I like discovering how users will actively think out a workaround which is was completely unintended for the designer.

For instance, here, the anti-bacterial spray is displayed, hung on the price tag of the sports shop’s shoe section.

Using water servers as weights to hold the tent down.

A gathering at the field. Why place the luggage there?

It may seem like it's done unconsciously, but actually, people are intuitively thinking when doing something. I believe there is always a universal idea or worry hidden in the background of a human reaction to their environment.

Discovering matters that people do not speak up about, or are still not fully understood in order to be verbalized. This observation of “out-of-purpose usage” is what will be at the core of KAIMEN’s activities.

5. Arriving at “a simple board” after updating the hypothesis

—How did the project move forward after the experimental results at MTRL KYOTO?

As we updated our hypothesis, the key aspects shifted from “it doesn’t need to be connected,” “it has to be easy to use,” to “one simple board is all we need.” However, I hadn’t completely discarded the idea of connecting the boards. I still wanted to put two or three together.

By then, we had finished designing “the given conditions for design.” In other words, “what we should design.” In search of an industrial design partner that would work with us to reach high-quality output based on this hypothesis ver.2, we ended up at f/p design.

To be continued in “ideaboard Series: Product Development Story #3 ”

(Interview by Mone Nishihama, NINI Co., Ltd., translation by Kyoko Yukioka, NINI Co., Ltd., and photos by Yukiya Sonoda)

▼Click below to see the original Japanese version / 原文はこちら