ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #7_Manufacturing 2 | Tackling Manufacturing Issues in Pursuit of Form Realisation

In December 2019, NKC Nakanishi Metal Works Co., Ltd. (referred to as NKC in the following) launched their new whiteboard, “ideaboard®.” Unraveled by the project members themselves, this series records the story of how the ideaboard was brought to life, and into ours.

《Past articles》

ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #1_ The Idea|On Persistently Nurturing a Seed Idea

ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #2_Design Development |Prototyping and Updating the Hypothesis

ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #3_Design Development|Collaborating with Design Agency, 'f/p design'

ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #4_Intellectual Property Strategy|Envisioning the Revenue Model for Designers

ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #5_Monitor Test |Verification of the Updated Hypothesis

ideaboard® Series: Product Development Story #6_Manufacturing |Collaborating with TOKIWA Manufacturing Co., Ltd.

The series continues where we left off with Riku Nagasaki, head of “KAIMEN” (the business design team reporting directly to the president at NKC). The simplicity of ideaboard’s form called for balancing out complex manufacturing requirements. We ask him about how TOKIWA Manufacturing, f/p design, and KAIMEN, embarked on their journey of tackling manufacturing issues.

Riku Nagasaki

head of KAIMEN

NKC BUSINESS DESIGN CENTER

1. Selecting materials that complicatedly affect each other within a simple form

ーWhat did you first embark on after finally deciding the ideaboard’s form?

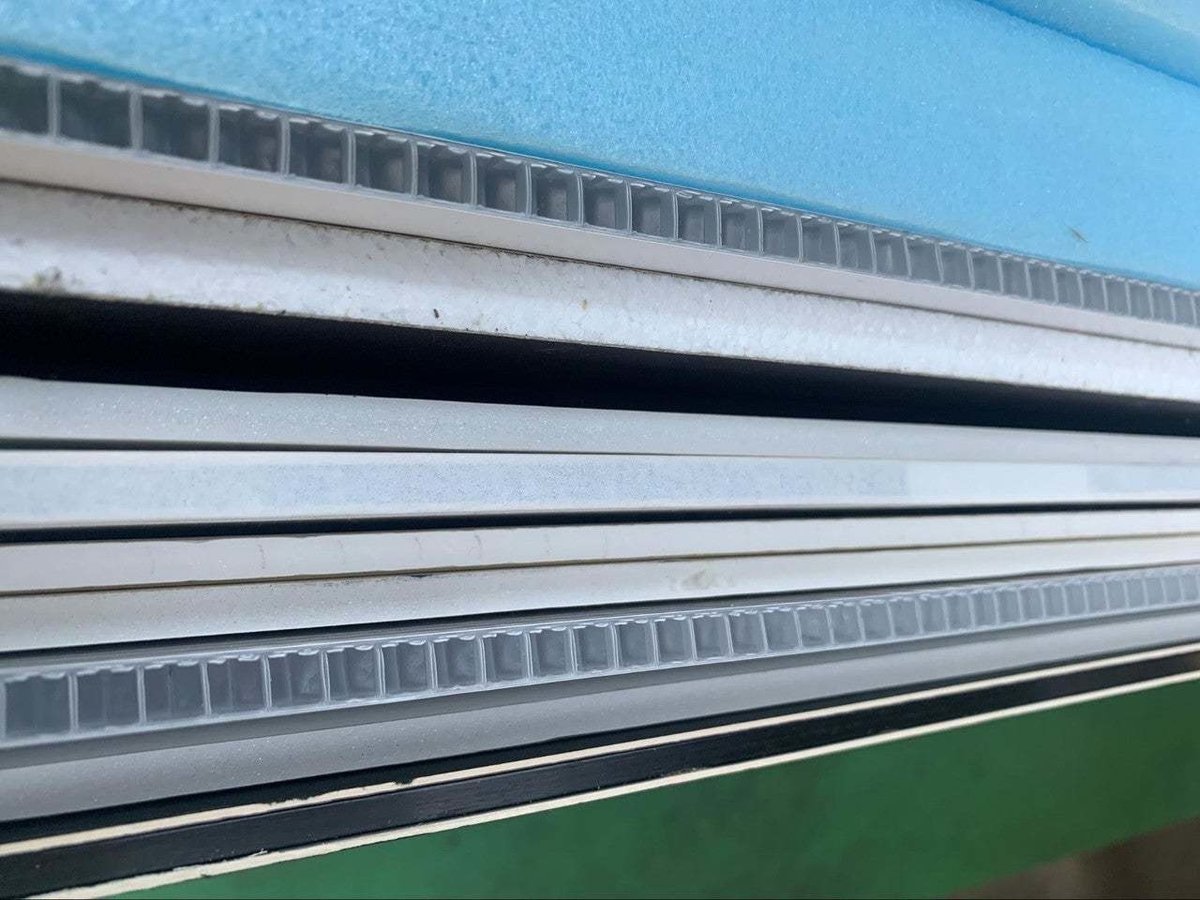

The discussion followed on to what type of core material we would use to realize the ideaboard’s form—honeycomb boards, corriboards, styrofoam, etc. The structural material would change everything—the weight, its tendency to bend, and durability. We were at the point where we knew the shape, but not the material, and we were basically feeling our way through the process. With f/p design at our side, we searched for possible materials and lined them up in our studio in Osaka, and compared them.

We hadn’t decided on what kind of material we would use, or whether we were going to use the typical sheet for whiteboards or just use some kind of paint, or even if it should be magnetic. Figuring out the numerous combinations of surface material and inner core material was a lot of work. We bought material as samples and tested them out—actually holding them and debating each one. There were ones that couldn’t hold their own weight to the extent that they would bend or materials that were simply just too heavy for one person to hold. There was also the problem of them having different widths. At this point, it was as though we were searching in the dark.

ーWhat kind of aspects did you give emphasis to when selecting?

The ideaboard is one single board, so first and foremost, there was the issue of the warpage. Even the one I used at my previous firm, KYOTO Design Lab, that had an aluminum frame around it, bent. It would bend vertically when tilted against the wall as well as bend horizontally, slightly twisting itself. Considering how prone it was to warpage even with the support of the aluminum frame, we knew we had to secure it with sturdy materials from both the core and surface.

At one point, we began to lose our confidence in our method of carving out homogenous material and pasting the surface material onto it. It Inevitably causes the ideaboard to become heavier and leads to bending. We contemplated making it lighter with other options such as using square carbon tubes as braces to reinforce the form instead and paste the surface sheet onto it—yet of course, we knew how costly that would be.

ーWere there any other aspects you considered besides the weight and warpage in selecting the surface/core material?

There was also the debate on whether we should paste the film for whiteboards directly onto the surface material or paste a sheet in between. If the inner side were to be cardboard, the unevenness would appear on the surface of the whiteboard film. Most ordinary whiteboards actually do have this uneven surface, and we didn’t necessarily require a completely smooth one, but we did want to raise the bar as much as possible on this aspect. F/p design also wanted to bring it up to the level of their usual output.

Therefore, what was decided at this point was that we would aim for the best in terms of quality. However, we made sure to have a plan B and plan C close at hand and proceeded with a broad mindset.

ーWeight, warpage, and quality of appearance. It seems there was a lot to consider in selecting the material when it is still during the initial stage of the manufacturing process.

It really was where we struggled the most. In that sense, ideaboard is maintained on a very delicate balance. The surface materials themselves have a broad variety to choose from and have various compatibility when pasted together. Some adhesives work and others don’t. The surface material, the core material, and urethane. We had three extremely difficult materials. Try to bring out one’s features, and the other’s would fade. Favor all and the whole product would become overly heavy. I would say this was the result of our endless considerations, the arrival at a very delicate balance.

ーHow did you assess the good and bad of this delicate balance?

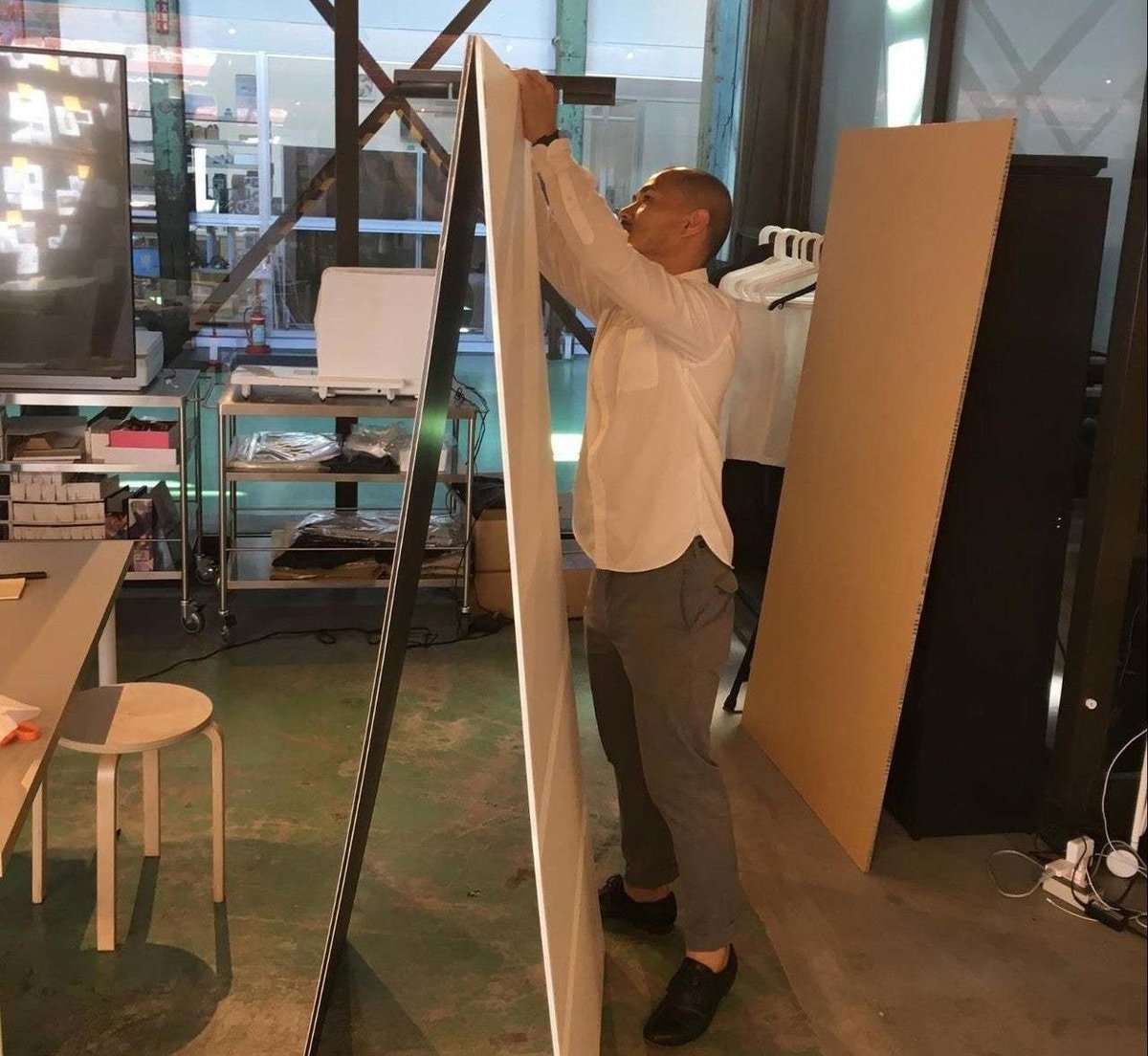

That would at all times be by the people—the users. Would someone completely unaware of the ideaboard feel it to be heavy when asked to hold it, or would one not mind? At this point, we knew it was impossible to make it into something astonishingly light. We were rather interested in specific numbers. When one would feel it to be lighter than expected, how much would it actually weigh? 3kg or 4kg? 4.9kg or 5.2kg? We were very grateful for TOKIWA Manufacturing who brought in every one of the prototypes they created. All of us held each one, feeling the weight ourselves and discussing whether it was too heavy or how it would bend. We took great importance in trying out the prototypes on actual people, and seeing what kind of impressions they would have towards it.

ーYou’re saying you would hold it at its actual size and combination of materials? That would require many prototypes, wouldn’t it?

Exactly. Normally, TOKIWA Manufacturing deals with major enterprises, receiving specific orders on how to manufacture their products, which I would think would be ensuring for them to move forward with their work.

However, as for ideaboard, since it is nearly a BtoC product, we have no idea who it would be sold by or where it would be sold. In a sense, for TOKIWA Manufacturing, even if it were to benefit future sales, the human/development resources spent in the ideaboard could end up being wasteful. In this regard, we couldn’t predict how invested they would become in this project. We definitely wanted to make it to its final form, but we didn’t know if we could. That’s why we appreciated it every time they came in with a new prototype. Of course, there was a set budget for them to work in, but I feel the amount of consideration they put in added up to be worth much more.

2. The commitment to white urethane and the issues caused by the white color

ーIn addition to the combinations of surface/core materials, I heard you put in a lot of time considering the urethane that would be used for the rim.

Yes, the issue of whether we should have white/black rims. We’ve previously mentioned this from what we observed from the monitor tests. Initially, over anything, we emphasized it being thin and light—something like one polished thin board of tofu. We were committed to making it more simple, more primitive.

In that sense, we first worked on the surface material—the melanin’s white color. This could possibly be altered, yet a huge investment would be required to do so, hence the decision to make it white was final. We then concluded that the rim should also be white to match the surface color. However, when saying “white,” we needed to take into consideration the hundreds and thousands of colors that resemble “white.” This process of finding “the same white color” was the crucial step of “color matching” or “color selecting” referred to in product design and industrial design.

In this project, we had our limitations in the variety of white colors we could use in regards to the budget and whether TOKIWA Manufacturing could handle it. The first was flexible urethane: a fairly cheap, and easy material to adjust its color. This material was prone to turn yellow, causing the type of discoloration you would see happen to an old computer sitting by the window. At first, color matching may be easy and it may be cheap, but we couldn’t agree to the rim turning yellow on its own and standing out. The next material was rigid urethane—one that wouldn't turn yellow. This cost more required extremely high temperatures during manufacturing and heightened the risk of deterioration of other materials. Either way, we were stuck.

We proposed we needed to actually make it and try it in order to consider anything. It turns out that white indeed tends to get dirty. From the smoothness and glossy look of urethane, we had thought that we could use it similarly to a whiteboard. However, in fact, there were countless tiny holes in the surface and as we continued to use the board, the black ink would seep into the holes and leave stains. We saw how easily it could become dirtier than expected. Therefore, since there had already been talk around a black rim, we conducted a monitor test using both white and black rims. As a result, users found the black rim to be far easier to use.

Make it black, and the issue of yellowing disappears. Obviously, we needed to choose a good black, but this would dissolve the necessity to match it to the color of the surface material. By switching to black, we were able to solve many of the issues that arose by committing to white. It also was easier for users to handle and put down. We struggled, but I feel that this was a worthy moment of a breakthrough in solving the issue in a great way.

3. Balancing out the quality and costs within the limitations of cast molding

ーAre there any other mentionable elements you took into consideration from the perspective of manufacturing?

Where to inject the resin when cast molding. Where to remove the air in place of the injected resin.

Moreover, due to the need to divide the mold in order to take out the made product, we needed to consider where to divide it. These elements are vital to any type of cast molding.

This is due to the fact that the holes made from injecting the resin and removing the air, and the lines made when dividing the cast will always leave a mark, which will affect the quality of appearance, resulting in post-processing and extra costs. The holes need to be minimum in size and made in places where they aren’t visible. Parting lines and post-processing must be considered. All of these elements are required to be weighed against each other and balanced out during decision-making.

In addition, since the process of setting the materials inside the resin mold is not entirely mechanized, human errors inevitably occur. This causes slight differences in the urethane cast’s width. The decision to make here is which extent to tolerate—would a difference of 1mm be withstandable? 0.5mm? Perhaps even 2mm? It was difficult to decide on the balance among the quality of appearance/performance, costs, and the limitations of cast molding.

Securing materials for the inner foaming agent was also a challenge. For foam agents, in the industries they are used in, there isn’t much of a commitment when it comes to getting the precise width. It’s one of those materials which are often used at sites where people don’t make much of a fuss about when there is a difference over 1mm. However, a 1mm difference would cause huge problems for ideaboard. In the case of cast molding, if there were to be a 1mm gap, the resin would seep through and the product would instantly become defective. The differences in width tolerated on the site of ideaboard are the most unbearable, slightest differences in the industries of foam agents. With an order utterly smaller than those of the industries they usually catered for, and strict limitations on errors, we ended up being rejected by many suppliers. Consequently, digging in both professional and personal relationships, and literally going the distance, TOKIWA Manufacturing went out of their way to find a firm that would supply materials.

At the stages of manufacturing, we were greatly helped out by f/p design and TOKIWA Manufacturing. As for myself, I felt I was almost going to shrink and disappear from feeling so grateful...

To be continued in “ideaboard Series: Product Development Story #8 ”

(Interview by Mone Nishihama, NINI Co., Ltd., translation by Kyoko Yukioka, NINI Co., Ltd., and photos by Yukiya Sonoda)

▼Click below to see the original Japanese version / 原文はこちら