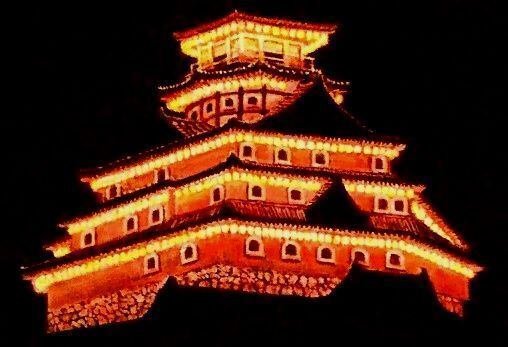

The Last Urabon Festival - Azuchi, 14 August 1581

Oil on canvas, 73×91cm, 2008-2021, M.Tsushima

The last Urabon Festival is one of the most iconic moments in Nobunaga's final years. It was held on 14 August 1581 at Azuchi, and was to be the last Urabon Festival for both Nobunaga and the Azuchi Castle.

Background

As Nobunaga grew his power and became influential in politics, he frequently visited Kyoto, 120 km from his HQ at Gifu. Nobunaga moved his HQ from Gifu to Azuchi, 50 km from Kyoto, where he built a castle on a lakeside hill. The construction of the castle began in 1576 and completed in 1579.

Urabon Festival is the Buddhist custom to honour the spirits of one's ancestors. It is held every year on the 15th of July of the old calendar. People make bonfires or hang lanterns in front of their houses to guide their ancestors' spirits home and escort them back to heaven.

The Urabon Festival at Azuchi in 1581 was held in an unusual manner. Nobunaga had his castle decorated with numerous lanterns and had his soldiers carry torches on streets and on boats in canals.

The festival was the first and the last. The castle was to be burned down in the following year, in June 1582, when Nobunaga was killed.

Accounts

Ota Gyuichi(1527-1613), a samurai who served Nobunaga, writes[1]:

15 July, Azuchi castle tower and Sokenji temple are hung with many lanterns. On the Shindo Street and on boats in the water are soldiers holding torch in the hands. Lights at the foot of the hill reflect off the water: it is ethereal and elegant. People gather to see the sight.

Luis Frois(1532-1597), a Jesuit missionary, writes[2]:

Every year vassals make a bonfire in front of their own houses, and nothing was burnt at Nobunaga's castle, but that night the complete reverse happened. That is, Nobunaga forbade any vassals from burning fire in front of the house, and only he had the upper castle tower decorated with colourful and gorgeous beautiful lanterns. With verandas surrounding the seven floors, it towered high, and innumerable lanterns looked like burning in the sky, giving a vivid landscape.

He gathered a large crowd of people holding torches on the street which started at a corner of our monastery, passed in front of it, and got to the foot of the castle hill, and arranged the people neatly on both sides of the long street. Many high-ranking young samurais and soldiers ran down the street. The torches are made of reeds, so when burning out, they emitted sparks. Those who held it intentionally showered sparks on the ground.The streets were filled with these fire, and young samurais ran over them. After a considerable amount of time, as the priests, monks, and children of Seminario relaxed and watched the festival fire through the windows, Nobunaga walked past the entrance to our monastery. The missionary and the other priests went out and took a deep bow to please him, Nobunaga chatted with them for a long time, asked if they had seen the festival, what they thought about it, and after asking a variety of other questions, he left them.

Venue

So, where is the best place to see the spectacular summer illumination?

There were four things illuminated: the castle tower, the Sokenji Temple, boats, and the Shindo Street. The place from where all these subjects can be seen, if any, is the best place to make the picture most beautiful.

We start with the Shindo Street.

The Shindo Street (New Street) was built in 1578 by the order of Nobunaga who wanted to attract the traffic from Gifu to Kyoto to the southern foot of the Azuchi castle hill. The street passed in front of the Jesuit monastery which was at the southwestern foot of the hill, and went eastward crossing a bridge called Hasuike Bridge over a canal. Nobunaga, after passing the Jesuit monastery, must have walked on the bridge.

At the north side of the street, according to the map of 1687 [3], there was a large swamp that was to be reclaimed to make rice fields in the 20th century. This was one of the waters, in which boats carried soldiers holding torches in the hands, and which reflected off the light.

Looking from the Hasuike Bridge, we can see both the castle tower and the Sokenji Temple on the hill.

The Castle Tower

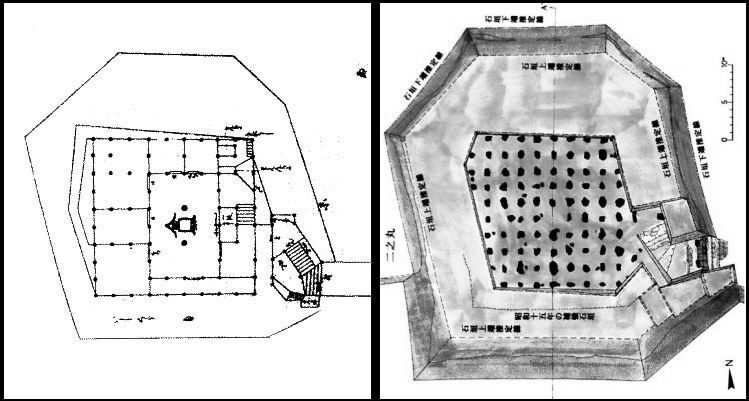

The Azuchi castle was destroyed in 1582, leaving nothing but stone foundations. The foundation of the tenshu (main castle tower) was covered with stones, pebbles and sand, before it was excavated and restored in 1940.

Though it is hard to picture the castle tower which existed only for three years, a clue to reconstructing it comes from the Seikado Bunko Archive in Tokyo where in 1969 Akira Naito, a professor at Nagoya Institute of Technology, discovered a floor plan called Tenshu Sashizu which was copied in 1676 by Ikegami Shimpei, a Construction Magistrate of Kaga province. Though the floor plan does not mention that it is of the Azuchi castle, Naito found that the plan matched well with the excavated foundation[4].

This revelation drove him to the meticulous study of the lost castle tower. Naito counted the number of wooden pillars, measured the space of each room on the floor plan and verified them with the record of the Azuchi Castle written by Ota Gyuichi. The Tenshu Sashizu also wrote the names of rooms, that also matched well with the Ota's document.

It is almost certain that the floor plan is of the lost Azuchi castle tower. It filled the missing information like the locations of windows and gables, and enabled Naito to reconstruct the model of the castle tower with both historical and architectural reality.

The tenshu was a seven-story building with the height of 33m. How the tower atop the hill with a relative height of 110m looked like was described vividly by Luis Frois[2].

In the middle of the castle, there is a kind of tower called tenshu, which is a different kind of architecture that is far more elegant and magnificent than our European tower. The tower has seven layers, and was built with surprisingly wonderful construction technology both inside and outside. In fact the walls inside are filled with portraits paintings that are coloured and gilded. The exterior is colour-coded for each of the seven layers. Some are lacquer paint used in Japan, decorating white walls with black lacquered windows, showing extreme beauty. Others are painted red or blue, and the top layer is all gold. The tenshu, as well as all other mansions, is covered with roof tiles that are, as far as we know in Europe, most robust and luxurious. They look blue, and all the tiles in the front row have golden round mounting heads. On the roof were mounted very elegant, elaborately shaped, magnificent figureheads. Thus those things make it, as a whole, a stately, luxurious and perfect edifice. The buildings on the hill, because of the height of the building itself, could be seen from a distance of many miles, as if it were poking a cloud. They are all made of wood, but do not look like so, both inside and outside, rather look like made of sturdy, solid rock and lime.

Thus, the silhouette of the castle tower became clear, however, there still remain some parts elusive. For instance, Ota Gyuichi writes that the seven layers of the tenshu were all black lacquered, while Jesuits write that the walls were all white except those of the top floor that were painted gold and blue. The clue to figuring out the real image, presumably, is on the folding screen called Azuchi Byobu on which Nobunaga ordered Kano Eitoku to paint the Azuchi castle and the town with details true to life and with utmost precision. The byobu was completed in 1581, sent by Nobunaga to Rome, gifted to Pope Gregory XIII in 1585, exhibited in the Vatican Gallery of Maps, and disappeared sometime in the 18th century.

Sokenji Temple

Sokenji temple is a Buddhist temple built at the same time as Azuchi castle. It was on the western ridge of the castle hill with the relative height of 81m. Timbered buildings were not newly built but moved from nearby temples and shrines. An account tells that in the late 18th century, there were 22 buildings large and small, but in 1581 there were four buildings and three gates. Among them the most conspicuous were the main hall and the three-story pagoda. The three-story pagoda, which was constructed in 1454, was moved from Chojuji Temple in Kouga to the present site when the Sokenji temple was built. The main hall appeared to be moved from another temple but was lost by a fire in 1854.

According to a regional geography book printed in 1805[5], the main hall was a two-story building, but there is no account describing the structure of the main hall in Nobunaga's period. It was 1994 when the excavation and research of the Sokenji temple ruin revealed the floor plan layout of the buildings at the time of the foundation of the temple. The layout of the cornerstones indicated that the main hall was an one-story building, which was typical in medieval Esoteric Buddhism temples[6].

Nobunaga's intention, however, by building the Sokenji temple was not to propagate Esoteric Buddhism but to deify himself. Luis Frois writes a diatribe against the arrogance of Nobunaga:

And in order to realize this profane desire, he ordered to build a temple on a round hill near his residence and away from the castle, and wrote a poisonous ambition and put it up. which was translated from Japanese to our language as follows:Nobunaga, the prince of all Japan, built the temple called Sokenji in the Azuchi castle, which gives pleasure and satisfaction to the viewer just by looking at it from far away, from the countries in the great Japan. The merits and benefits endowed to those who worship and respect the temple are as follows:First, if you are wealthy and come to worship this temple, you will increase your wealth, and if you are poor, low-ranked, and come to worship this temple, you will also be wealthy by the merit of visiting this temple. Those who do not have children or heirs to increase their offspring will soon be blessed with offspring and longevity, and will have great peace and prosperity.Second, you will live long until eighty years old, your illness will heal soon, your hopes will be fulfilled, and you will have health and peace.Third, on my birthday, as a holy day, visit the temple.Fourth, for those who believe all the above, there is no doubt that the promise will always come true. Thus, the evil ones who do not believe these things will be destroyed both in this world and in the afterlife. Therefore, it is necessary for all to always devote great worship and respect to this.Nobunaga, as his entire life reveals. was not only always unwilling to worship gods and Buddha, but also ordered to ridicule and incinerate them, but this time, manipulated by the devil's solicitation and instinct, he ordered people to bring idols, that were visited by the largest number of worshippers in Japan, from all over the countries. His purpose was to use them as nets to capture more their faith to himself. A shrine of gods, usually in Japan, has a stone called Shintai. It indicates the heart and substance of a god's image, but Azuchi did not have it, Nobunaga said that he himself was a god. But, in order not to be inconsistent, that is, in order not to make a worship to him inferior to that to other idols, when a person brought a stone called Bonsan, which was apt to it, he ordered to build a sort of shrine or an altar without a window, and store the stone in it.

The main hall is considered to have a two-story extension to house the Bonsan stone when it was moved to Azuchi castle[6]. The Sokenji temple, though the buildings were of typical Buddhist temples, was not an ordinary Buddhist temple to worship Buddha, but a sort of shrine to worship Nobunaga as a god. The temple, therefore, needed a priest who appreciated Nobunaga's cause to deify him. The one invited to be the chief priest of the Sokenji Temple was Gyosho, who was from Tsushima Shrine in Owari Province, which was the shrine Nobunaga respected, protected and supported for its construction since his early years.

The Festival

Urabon Festival is the Buddhist custom originated in China in the 6th century and introduced in Japan in the 7th century. At the festival night, people make bonfires or hang lanterns in front of their houses to worship their ancestors' spirits.

Nobunaga, however, made it not a Buddhist event. He prohibited people from making bonfires in front of their houses. What should be worshipped, to him, was not their ancestors' spirits, but his own represented by the Azuchi Castle and the Sokenji Temple. Nobunaga lit his castle and the Sokenji Temple with many lanterns. Around the castle, boats were on the waters carrying soldiers holding torches, the lights reflected off the waters.

So how did Nobunaga come up with the idea of using fire and water effectively to make the festival more impressive? What was the inspiration?

There are some fire and water festivals in Japan that might associate with the Azuchi Urabon Festival, like Kyoto Gozan Okuribi or Osaka Tenjin Festival. Among them, one of the most inspiring to him, possibly, was the Tsushima Tenno Festival.

Tshushima, near Nobunaga's birthplace, was the town having developed around the Tshushima Shrine which was apparently founded in 540AD. The shrine, visited by many believers, was along the Tenno river on which banks commerce flourished by the traffic of thousands of boats. Tsushima Tenno Festival was annually held in summer since around 1500. A record written in 1558 says that Nobunaga saw the festival from the Tenno Bridge[7].

The Tenno Bridge does not exist today. The Tenno River was buried at the Tenno Bridge in 1785 to improve the traffic to Tsushima Shrine, and was further reclaimed in 1901 to prevent flooding. There is a pond left at the Tenno Bridge site where the festival is still held annually in the 21st century.

What Nobunaga saw at the festival seems almost same as we see in the 21st century. At the festival five showboats that each is illuminated with 365 lanterns float in the pond, that are also seen in the byobu screen painted in the 17th century[8].

The image of lanterns of the Tsushima Festival is reminiscent of the description of the Azuchi Festival written by Lois Frois, though, what were hung with lanterns at the Azuchi Festival were not boats but the castle tower and the Sokenji Temple. So, how to hang the castle tower and the Sokenji Temple with numerous lanterns?

One of the most viable ways to hang many lanterns is to hang ropes on hooks under the eaves of the buildings. A three-story pagoda in a Buddhist temple are hung with bronze bells called futaku at its roof corners. The three-story pagoda of the Sokenji Temple has no futaku today, nor in the picture drawn in 1805, but it has hooks at its eaves.

The hooks are found at each corner of the roofs, that allow a rope to extend from corner to corner under the eaves to hang a series of lanterns. As other temples in Japan, the main hall must have had similar hooks at its eaves. As for the castle tower, Ota Gyuichi writes that it hung twelve futakus[1], so it was possible to replace futakus with ropes to hang lanterns.

While the hilltop buildings were lit with lanterns, at the foothill boats on the waters were lit with torches. The waterways in Azuchi, like in Tsushima, has changed since the 16th century. Swamps and streams were reclaimed to build rice fields, roads and towns. There are some vestiges of a swamp in the 21st century at the southern foot of the castle hill. In the 16th century, the swamp was connected to the Lake Biwa that generated boat traffic to Kyoto and north coast area. It was not hard, therefore, for Nobunaga to introduce a lot of fishing boats or merchant vessels at the festival.

A caveat is that in summer there are clumps of reeds growing, that narrow the waterway. The Lake Biwa is famous for its reeds production. In the darkness of reed fields, the reed torches would burn out to cast light on the waterway, to guide a queue of boats toward the illuminated castle that looked like burning in the sky.

Details

References

[1] 信長公記, 太田牛一

[2] 日本史, Luis Frois

[3] 近江國蒲生郡安土古城図 (1687)

[4] 復元 安土城, 内藤昌, 2006

[5] 木曽路名所図会(1805)

[6] To surpass even the Buddha: a study on the reconstruction of the main hall of Soukenji-temple in Azuchijo-castle by Oda Nobunaga. ,Bulletin of Tottori University of Environmental Studies, 2010

[7] 愛知県史資料編10中世3, 2009

[8] River Festival at Tsushima Shrine, Kano School (17th century)