Life Changes; Memory Changes; Now is Forever Gone, an essay by Leith Morton (Tada no Jiji)

Reading and translating the poetry of Yasuhiro Yotsumoto, I noticed his postscript to his 2012 volume Nihongo no Ryoshū, and translated a section of it in my recent volume of translations of his poetry and the poetry of Minashita Kiryū, and Soh Sakon. Minashita is still a young writer (at least from my point of view— I am an old man or to use the delightful Japanese phrase: “tada no jiji”) and so the changes in her work are difficult to predict. The shift in Soh’s poetry from longer to shorter forms stands out but the overall sense of a poet obsessed with the consequences of the greatest tragedy to befall Japan in its long history—World War 2—inhabits most of the verse by Soh; from kappa to Jōmon, irrespective of the change in verse form. Yasuhiro Yotsumoto’s verse encompasses several categories of writing: from Japanese politics to his own personal history, among others. But what caught my attention was that Yasuhiro commented on the change in his own poetry occasioned by a shift from narrative verse to “language poetry” with no narrator.

It is now over a quarter of a century since Tanikawa Shuntarō, in the pages of Gendai Shi Techō, engaged in a debate with the poets Hiraide Takashi and Inagawa Masato over the issue of “language poetry”. And we all recall much earlier the poet Suzuki Shiroyasu’s masterpiece “Shishōsetsu teki puapua” published in 1967, its use of nonsense language perhaps symbolizing the decade of the 1960s, the poetry of which the critic Kokai Eiji later characterized as “words, words, words”. We may also cite as evidence Tanemura Suehiro’s influential article “Nansensu Shijin no Shōzō”, serialized in Gendai Shi Techō between 1968 and 1969. So if Suzuki and his later followers in verse, such as Nejime Shōichi, began the move to language poetry then we could say it has been almost half a century since it began to occupy the minds of poets in Japan. And this is to entirely ignore the writing of modernist poets in Japan from the end of World War 1, and such accomplished and obsessed writers of nonsense poetry as Takahashi Shinkichi (I haven’t forgotten his “mad” verse, so similar to Gerard Manly Hopkins) in the 1930s.

The issue does not go away, as Yasuhiro has demonstrated. Why? Because poetry is written in language: poetry is, in the end, just ink on paper or perhaps cyber text, which, after all, is simply another version of ink on paper. If poetry can be compared to chess, then it is simply a game, a cognitive tawamure, as once was described to me by an expert in renga, who said renga was just a game designed to please (male-male) lovers. Or so it was in the medieval era. Today it is perhaps an idle curiosity of professors, or a game played by the poet Ōoka Makoto once upon a time.

This brings me to the now: an illusion perhaps, as it cannot be captured except by fallible memory. You object: what about archives, old paper repositories, ebooks, the estimable Aozora Bunko. Is this really the now? The fact remains that when we capture these artifacts in memory, they become just another layer of illusion, memory mediated by ego, vanity, love, lust, ambition and dream. And remember, if we forget (which we do, all the time), then in a very real sense, they cease to exist.

I am reluctant to comment much on contemporary poets. Especially young poets. Why? Because of my deep respect and admiration for someone who dares to write poetry (don’t take this too seriously, after all, I am a poet myself, and even worse a translator—as the Italians have it, a liar). And also because, by and large, poets possess such fragile egos. We rarely earn much money unless we switch to prose, copy-writing, academia or maybe acting (but only if successful). The world, on the whole scorns us: “so what?”, you say. And I agree whole-heartedly. Also, I have left Japan after living there continuously for 11 years, and interruptedly, for 20 years. The now pursues me in my dreams: the dreams of a Japanophile, a lover of poetry, a pensioner, a grandfather, and one who strolls by the river. Yasuhiro frets about losing his German; I fret about losing my Japanese—where is it? Can I put it on a lease, like a dog? The now looms ever larger.

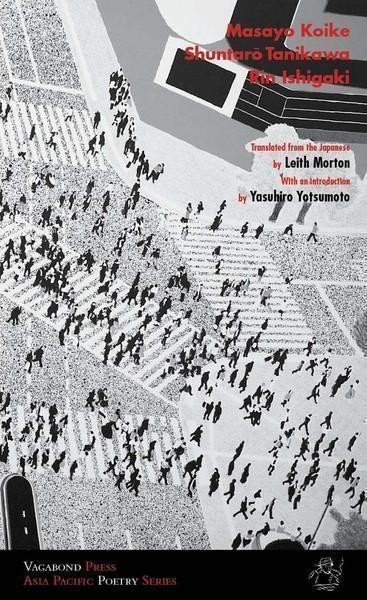

I could mention the names of contemporary poets whose work I want to see more of. Hey, that’s everybody! Last week in Shiga Prefecture, at the admirable Junkudō, I bought a volume of verse by Saihate Tahi, and another by Yoneya Takeshi, and a study of the poetry of Tōge Sankichi. With one exception, none of these poets are particularly young (or even alive) but, for me, they are as much of the now as my long dead friend Kusano Shinpei and my dear friend Tanikawa Shuntarō (all of whom I have translated in book form in the past). Do contemporary poets struggle with the issue of language as much as Suzuki Shiroyasu? Absolutely! Do they artfully construct selves as skillfully as another great (but, sadly, dead) poet—Ishigaki Rin—whose work I have also translated in book form? Of course! No self can be anything other than self-constructed. There are many wonderful poems by Japanese poets that I could cite that make this point, but, hopefully, you have read them too, and so I don’t need to cite them. One of the most beautiful things about Koike Masayo’s poetry is how she twists and turns so that memory is the now and the now is memory: we don’t know where we are. A little like Minashita Kiryū’s digital games in poetry.

Do you know where you are? Are you here in my life-memory or in my rather large library of Japanese poetry? Where am I? I’m not outside the library. I am the library.

About the author (Quoted from Amazon): Leith Morton was born in Sydney, Australia, in 1951. He graduated from Sydney University after obtaining a PhD in Japanese literature, and was soon appointed to a lectureship and senior lectureship in Japanese at his alma mater. He subsequently held professorships in Japanese at Newcastle University (Australia) and in comparative literature at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, where he currently teaches. He began writing poetry (and playing football) as a teenager and his first books were all poetry collections. Since then he has also written books on Japanese literature and culture in both English and Japanese, as well as translating into English a number of volumes (poetry and prose) from Japanese. For a full list of his books, at present numbering over 20 volumes, see his website at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. His latest book of poetry is called 'Tokyo: A Poem in Four Chapters' (2006). He is currently translating the tanka poetry of Samio Maekawa (1903-90), a pioneer modernist tanka poet, and has written a book in Japanese on Akiko Yosano (1878-1942), the greatest woman poet of 20th century Japan. Apart from his family, he has two great loves: poetry and football--difficult to combine together--and he is the first foreign soccer player to represent a Japanese city (Sakai) in the amateur intercity league. He supports Everton in the English Premier League, Newcastle in the Australian A League and Tokyo FC in the J League.

For books by Leith Morton from Vagabond Press, follow the link below:

https://vagabondpress.net/products/leith-morton-tokyo

For his other books available from Amazon;

https://www.amazon.com/Leith-Morton/e/B001I7BGKC

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?