Yellow mountain, ice cave

★10月1日公開の動画「黄色い山、氷の洞窟」の朗読原稿の英訳です。

Along the road to Sar Aghaseyed, we found the "Ice Cave."

Nestled within the vast Zagros Mountains in western Iran, this cave lies on the "Yellow Mountain," where, even in the height of summer, natural ice persists.

"Is there truly an ice cave?"

"Who knows? But they say the nomadic Ashooyar people make use of its ice."

Our guide and driver, Imam, replied carelessly.

It was then that I first heard of the Ashooyar. They are a nomadic people, spending the summer working the mountain slopes of the Zagros, and in winter, they tend their flocks in Bandar Abbas, far to the south. When the season calls, the men walk seventy to eighty days to reach the warmer pastures. Wherever they go, they settle near water and guard their traditional way of life.

Their "mountain work" refers to labor on the "Yellow Mountain." They harvest rare mushrooms, some fetching over a thousand dollars per kilogram, and gather herbs for a tea that causes both euphoria and addiction. It must be those mushrooms that keep them looking so clean and well-kept. One wonders who buys that strange, drug-like tea.

As mysterious as the Ashooyar themselves, the "Yellow Mountain" hides its own secrets. According to Bahman, one of the Ashooyar, the mountain contains vast amounts of magnesium. Once, an aircraft flying over its summit crashed, and ever since, the skies above the "Yellow Mountain" have been forbidden to planes.

As we made our way toward the "Ice Cave," Imam, he is a city boy, hesitated.

"Imagine what awaits at the summit," Bahman said. "That alone will make your body feel lighter."

Imam chuckled uneasily at Bahman's words, which seemed to carry a connection to the mountain's spirit.

"A true mountain boy," Imam muttered, his smile faint.

Listening to their exchange, I grew more intrigued by their way of life. There is something profound in the worldview of mountain people. I began to wonder—what beliefs shape their connection to this harsh land?

The next morning, leaving Imam looked reluctant to climb the mountain behind, I chose to climb the mountain with Bahman.

"Yellow Mountain," called "Zard Kuh" in Persian.

Towering at 4,221 meters, it is the source of the Karun River, Iran’s longest river, whose waters flow to the distant Arabian Gulf. Since ancient times, the melting snow from "Yellow Mountain" has sustained Persian civilization. Today, it remains Iran's largest water source.

Gazing up at the mountain from below, its brown slopes gave way to a pale, almost white hue halfway up. Was it the difference in the rock’s composition? Or perhaps the strong presence of salt?

As I pondered these thoughts, we began our climb. Within minutes, I regretted coming.

The ascent was like hiking Mount Fuji’s seventh station—a steep incline covered in loose gravel, where even a few steps left me breathless.

"This for an hour and a half?" I muttered, disheartened from the start. Glancing around, even the locals, climbing behind us, were struggling for breath. Only Bahman remained unaffected, his stamina unshaken, and Imam’s mocking phrase "mountain boy" echoed in my mind.

Had that rugged path continued for the full hour and a half, I might have given up. But mercifully, the rough terrain soon passed, and the spectacular views carried me through the challenge. At last, we reached the top, and before me lay an expansive glacier stretching across the valley.

How could such snow survive in this blazing heat? The pale rocks seen from below were not rocks at all but compressed glaciers, frozen solid and mixed with earth.

I chipped away at the surface, exposing rough, white snow beneath.

We began to form snowballs—Bahman threw one, then I another, until we found ourselves in the midst of a playful snowball fight. In this sunbaked desert of rocks and heat, we played like children in winter.

Caught up in the fun, I threw snowballs wildly, and Bahman laughed, gesturing to me to be careful not to hit anyone. He pointed to a groove in the snow, which had formed a natural path. It was faster—and safer—to slide down than to walk. Cheering could be heard from other hikers, young and old alike, all enjoying the natural slides. A child at the bottom, having slid on their backside, looked embarrassed as they patted their wet trousers.

I crouched down, balancing on my shoes as I slid swiftly along the smooth surface, like gliding over glass. A cool breeze, chilled by the ice, blew upward, cooling the sweat on my neck.

At the end of the snowfields, where the rugged riverbed emerged, the "Ice Cave" finally revealed itself.

Snow and ice arched over the flowing river, forming what seemed more like a bridge—or perhaps a roof. The river had carved its way through the glacier, tunneling beneath the thick walls of snow. How had the meltwater breached such a solid mass of ice?

The cave's interior was riddled with bumps and hollows, as though shaped by a giant hand. It was as if the spine of the world had been turned upside down, forming a ceiling that stretched on like an endless desert dune, hanging like stalactites into the darkness.

From the mountain’s peak, water dripped incessantly. The relentless summer heat gnawed away at the "Ice Cave," carving into its walls and creating a dreamlike landscape of countless frozen peaks. I had imagined something like the Narusawa Ice Cave at the foot of Mount Fuji, but in reality, this "Ice Cave" felt more like a vast natural igloo or a tunnel through snow.

A wonder like this could only belong to the mysterious "Yellow Mountain."

At the cave's entrance, threads of melting snow fell like silk, and inside, a dim light akin to that of a limestone cave greeted us. The walls of snow felt like polished porcelain, with patches of clear ice breaking through. It was no longer snow but pure white ice. How many years had it been frozen like this?

The river flowing through the "Ice Cave" reminded me of a scene from Natsuki Ikezawa’s novel, where the ancient ruins of Oniros in Afghanistan come to life. The stream, tinged with blue, danced along the golden rock faces, evoking a sense of nostalgia. The water of the Pamirs, still vivid in my memory, had that same striking shade of blue.

Bahman stepped lightly across the stones and scaled a near-vertical rock face with ease, gathering herbs as he went. His movements were graceful, his steps sure, both uphill and down.

The dreamlike scenes of these two worlds overlapped, echoing in my heart as if from another realm.

Though the Zagros Mountains may seem barren at first glance, underground streams nourish the lush valleys below. In the summer tent villages, this abundance can be felt in full, though the days scorch at over forty degrees, and the nights chill with a temperature drop of nearly thirty degrees. For five months in winter, the roads are sealed off by the snow.

Life here is undoubtedly harsh.

Yet the ruggedness and bounty of the "Yellow Mountain" and the "Ice Cave" lend an air of mystique to the Ashooyar people. Perhaps it is from these conditions that their enigmatic aura is born.

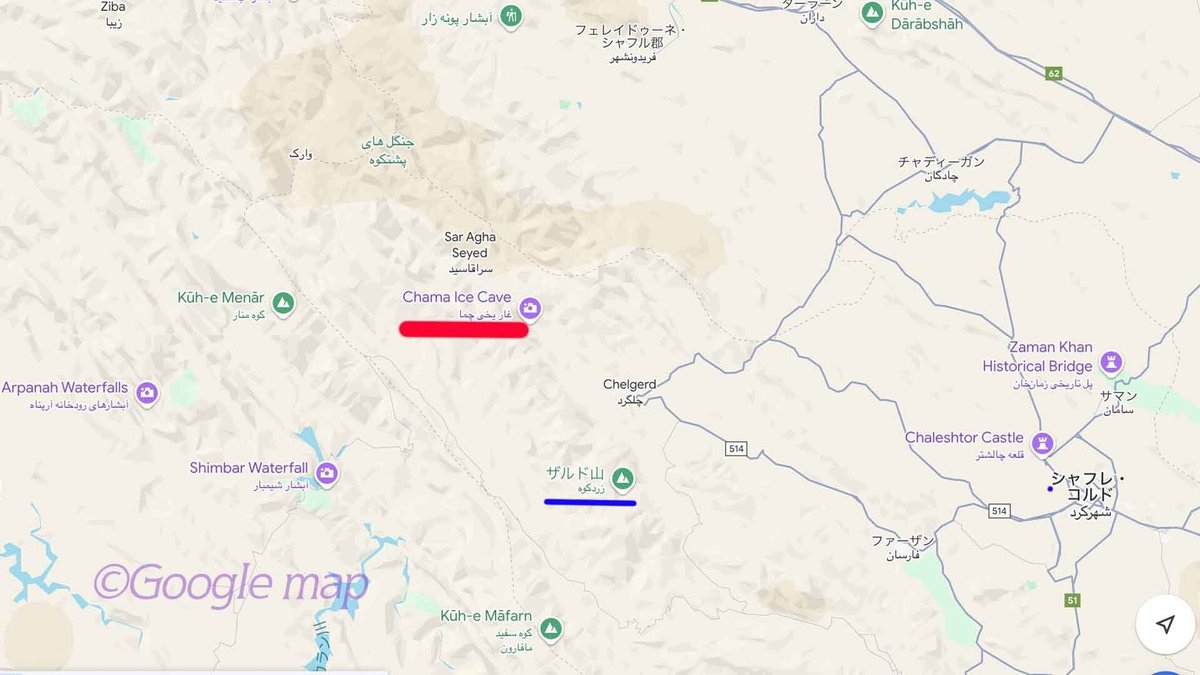

Directions to "Yellow Mountain, Ice Cave"

Location: Chama Ice Cave in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province

Directions: From Isfahan, take a taxi for about 3 hours.

Follow Route 514 from Shahr-e Kord, passing through Chelgard Village.

After driving 25 kilometers from Sheikh Ali Khan Village, you will see a sign for the "Ice Cave" on the left side of the road.