Made in China 2025 and Industrial Policies: Issues for Congress, CRS, Dec. 12, 2024.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC or China) aims to

gain a global economic and technology leadership position

through a range of state-led industrial and related science

and technology (S&T) policies. These policies feature a

heavy government role in directing and funding PRC firms

to acquire foreign technology and related capabilities—

including basic and applied research and talent—in areas

where the United States has long been a global leader and

has strong comparative advantages. Some Members of

Congress have expressed concern that China’s policies, if

successful, could undermine U.S. technological leadership,

further shift advanced technology, production, and research

to China, and support a wide range of China’s technological

advancements, including in defense. The scope and scale of

China’s efforts are evident in the amount of state direction

and support devoted to these efforts; PRC policies to lead

across the entire value chain (rather than just segments of it)

in key advanced and emerging technologies; and the tactics

China uses to target and acquire U.S. and allied capabilities.

Overview

In November 2022, at its 20th Party Congress, the

Communist Party of China (CPC) reiterated its focus on

technological innovation as the core driver of China’s

development, a focus it first set in its Medium- and Long-

Term Plan for Science in Technology (MLP) (2006-2020)

and reaffirmed in its MLP for 2021-2025. These MLPs call

for advancing China’s technological and scientific self-

reliance and advocate for assertive PRC corporate efforts to

acquire foreign technology and knowhow.

To implement the 2006-2025 MLP, in 2015, China’s State

Council issued Made in China 2025 (MIC2025)—a broad

set of industry plans to boost PRC competitiveness by

advancing China’s position in the global manufacturing

value chain, “leapfrogging” into emerging technologies

where there are not yet defined global industry leaders and

standards, and reducing reliance on foreign firms. PRC

plans rely on foreign technology and research to develop

PRC capabilities and talent. MIC2025 stresses “indigenous”

innovation, a process that often involves the acquisition,

absorption, and adaptation of foreign technology by PRC

entities, which may later recast these capabilities as their

own. This “indigenous” strategy obscures the extent of PRC

state ownership and control of PRC firms, and the role PRC

firms may play in advancing PRC development goals.

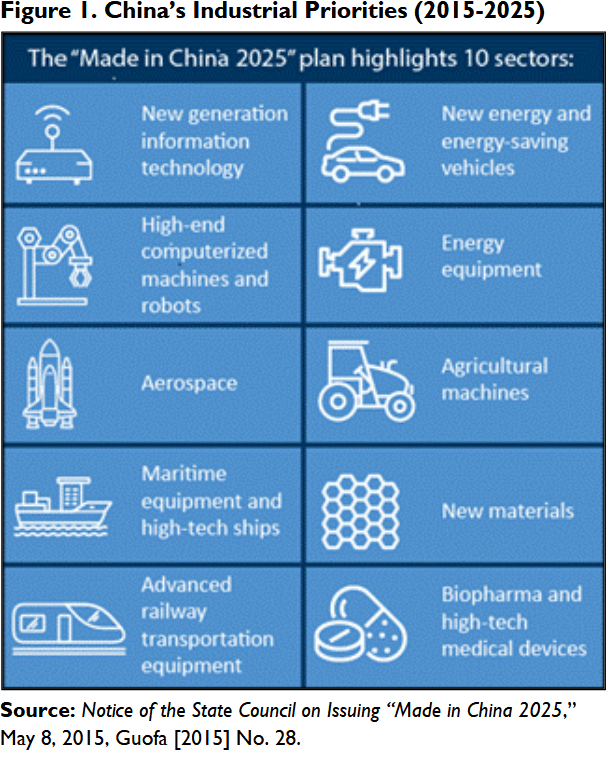

MIC2025 calls for technological breakthroughs in 10

sectors (Figure 1) and support for a range of sector-specific

plans. These plans aim to make China the leader in all parts

of the global value chain, and to increase the share of inputs

and finished goods produced in China and worldwide by

PRC firms. (Figure 2.) For semiconductors, for example,

this includes leadership in the full supply chain (e.g.,

design, operating systems, production, packaging, testing,

equipment, and materials) by PRC firms. MIC2025 is

focused on advanced manufacturing and on transforming

China’s economy from one that assembles goods to one that

invents the products it makes. Specific goals include the

following:

By 2025. Boost manufacturing quality, innovation, and

labor productivity; obtain an advanced level of technology

integration; reduce energy and resource consumption; and

develop globally competitive firms and industrial centers.

By 2035. Reach a level of development that is on par with

global industry at “an intermediate level,” improve

innovation, make major technology breakthroughs, lead

innovation in specific industries, and set global standards.

By 2049. Lead global manufacturing and innovation with a

competitive position in advanced technology and industrial

systems. (This date coincides with the 100th anniversary of

the founding of the PRC.)

China’s current economic development plan, the 14th Five-

Year Plan (FYP) for 2021-2025, promotes MIC2025 goals

by seeking to strengthen PRC-controlled supply chains in

order to bolster MIC2025 priority industries. The FYP also

calls for expanding the use of antitrust, intellectual

property, and technical standards tools to set market terms

and promote the export of MIC2025 priority goods and

services. The FYP also directs the expansion of foreign

research ties for the development of PRC capabilities in

MIC2025 areas. Deliberations on the 15th FYP are slated to

start in 2025.

Market Effects

China has emerged as a global leader in some emerging

manufacturing (e.g., solar panels, electric vehicles, drones)

and heavy industry (e.g., shipbuilding and high-speed rail)

sectors. Progress in developing capabilities in other sectors

(e.g., aerospace, agricultural equipment, and robotics) has

been slower. China has made gains in semiconductors, in

part through foreign ties (acquisitions, partnerships, and

technology licensing), but still depends on foreign tools and

equipment, research, and advanced chip production. As

PRC firms take a leading position in China in sectors such

as electric vehicles (EVs) and information technology,

some foreign firms are struggling to compete in China. As

MIC2025 products come to market, PRC firms are looking

to exports for growth and are facing increased scrutiny,

restrictions, and competition as foreign governments move

to promote domestic industry, restrict PRC firms, and

counter MIC2025 policies (see below). Other foreign ties

remain open to China (e.g., open-source hardware and

software technology, overseas investment, and research).

U.S. Concerns and Policy Response

MIC2025 has been a U.S. policy focus because of the PRC

tactics it has incentivized, such as technology transfer,

licensing and JV requirements, IP theft, and state-funded

acquisitions of foreign firms in strategic sectors. U.S. and

foreign industry groups have expressed concerns that MIC

2025 policies distort competition in strategic industries,

create overcapacity, and systematically drive foreign

technology transfer to China. Some say that its tight market

controls enable the PRC government to pressure foreign

firms to adhere to its demands. The scope and scale of PRC

state-led efforts are unprecedented as to the amount of state

funding involved; stated ambitions to lead in all parts of

global supply chains; and targeting of foreign capabilities.

The U.S. government has sought to counter MIC2025 and

related practices that it assessed unfairly advantaged China,

distorted trade, and strengthened PRC technology and

military capabilities. In 2018, for example, the Trump

Administration invoked Section 301 of the Trade Act of

1974 and imposed tariffs on most imports from China, after

finding that China’s policies harmed U.S. stakeholders. In a

January 2020 bilateral agreement, China agreed to some IP

and technology transfer commitments; other U.S. concerns

were unresolved. The U.S. government has not reported on

enforcement of these commitments. The Biden Administra-

tion continued most of these tariffs and raised tariffs on

some PRC goods (e.g., EVs, EV batteries, semiconductors,

medical products, cranes, solar cells, and aluminum and

steel items). The U.S. government also ramped up IP

enforcement and scrutiny of China’s role in federally

funded research. New rules seek to ban PRC-connected

vehicle technology from U.S. markets and restrict advanced

semiconductor technology exports to China.

China’s Industrial Policy Approaches

Tax, trade, and investment measures. China uses tax

preferences to incentivize foreign firms to invest in production

and research and development (R&D). It uses standards, IP,

competition, and procurement policies, and other terms to

facilitate the transfer of foreign know-how to PRC entities and

use PRC suppliers for key components.

Forced joint ventures (JVs) & partnerships. China’s formal

regulations and informal practices require a foreign firm to

partner with a PRC entity to operate in China and drive foreign

firms into JVs. In many sectors (e.g., aerospace), China leverages

its role as a major purchaser to press for JVs and technology

transfer in order to develop indigenous capabilities. In most cases,

the foreign firm’s partner is a state firm or the PRC government.

Government subsidies. PRC government guidance funds

(GGFs) channel state funding to PRC firms for domestic R&D and

overseas acquisitions. Almost 1,800 GGFs tied to MIC2025

sought to raise $1.5 trillion and by 2020 had secured $627 billion

toward this target. GGFs often take a stake or board seat in firms

they fund, and can influence corporate decisionmaking.

Foreign acquisitions. GGFs target and fund acquisitions of

foreign firms and use foreign firms’ expertise, IP, talent pools, and

business networks to build China’s capabilities.

Technology licensing & equipment. Foreign technology and

equipment fill key gaps in China’s current capabilities. PRC firms

are members of U.S.-led open-source technology platforms (e.g.,

RISC-V, the Open Compute Project, and the ORAN Alliance).

Since 2014, U.S. semiconductor equipment exports to China have

increased nearly five-fold as China seeks to make its own chips.

Talent recruitment and training. China encourages the

return of PRC expatriates and the hiring of foreign talent. Many

PRC and PRC-tied technology firms (e.g., Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent,

and TikTok) have U.S. R&D centers that partner with U.S.

universities. Many PRC nationals participate in U.S. federally

funded research in areas that overlap with MIC2025 technologies.

Issues for Congress

Some Members have sought to restrict trade, investment,

trade, technology, and research ties with China; shift supply

chains out of China; and prohibit PRC firms in federal

procurement and infrastructure. Congress has enacted

legislation to strengthen foreign investment review (P.L.

116-801) and export controls (P.L. 115-232); support U.S.

capabilities in semiconductors (P.L. 117-167), EVs, and

renewables (P.L. 117-169); and penalize China for IP theft

(P.L. 117-336). Congress may deliberate:

• The efficacy of U.S. policies (in design and in practice)

in countering China’s industrial policies;

• Whether a growing state role in PRC companies calls

for treating PRC firms differently;

• How U.S.-PRC trade, investment, technology, and

research ties affect U.S. competitiveness and U.S.

capacity and options to counter PRC policies.

Karen M. Sutter, Specialist in Asian Trade and Finance

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10964