Shaky Signal, The Wire China, Apr. 30, 2023.

By Brent Crane

Qualcomm is optimistic about its China business. Should it be?

Last month, Cristiano R. Amon, the amiable young chief executive of Qualcomm, took the stage at the 2023 China Development Forum, an annual gathering of multinational CEOs and government officials in Beijing. The American business community — wary of awkward optics during a time of grim congressional hearings, industrial sanctions and exploding spy balloons — largely kept their heads down at the press-heavy gathering. But Amon, beaming in a sponge-yellow tie, sounded a decidedly upbeat note for his American wireless firm.

“We are proud of the deep relationships we have built over the past 30 years [in China], and the new partnerships we are building today,” he said, before going on to praise China’s “digital transformation.”

The fact that Qualcomm — a $130 billion*1 behemoth in the telecom industry — was able to strike this celebratory mood is a testament to both its political savvy and its all-encompassing innovations. Today, virtually every smartphone on the planet relies on the semiconductor technology created and owned by the San Diego-based company. It is, in other words, in the crosshairs of not one, but two of the most contentious issues in the ongoing ‘tech war’ between the U.S. and China: semiconductors and telecoms.

(*1 The most recent market capitalization of the publicly traded firm.)

Qualcomm — an amalgamation of the words “quality communication” — has been the largest fabless*2 semiconductor company on earth for more than a decade. Its golden portfolio boasts some 140,000 patents across over 100 countries, with many of these showcased on the first floor of the company’s glitzy headquarters. Royalty payments for the company’s wireless intellectual property constitute the bedrock of its business model, with fees for manufacturers using Qualcomm’s intellectual property typically constituting around 4 percent of the total sale price of a handset.

(*2 An industry term meaning “without fabrication facilities, or fabs.” In other words, Qualcomm does not manufacture the chips it designs.)

“You basically can’t connect to a cell network without using Qualcomm’s intellectual property,” says Christopher Miller, a Tufts historian and the author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology. “It’s been a great strategy for them being in every smartphone. But it also means they have to deal with a whole range of political and regulatory regimes.”

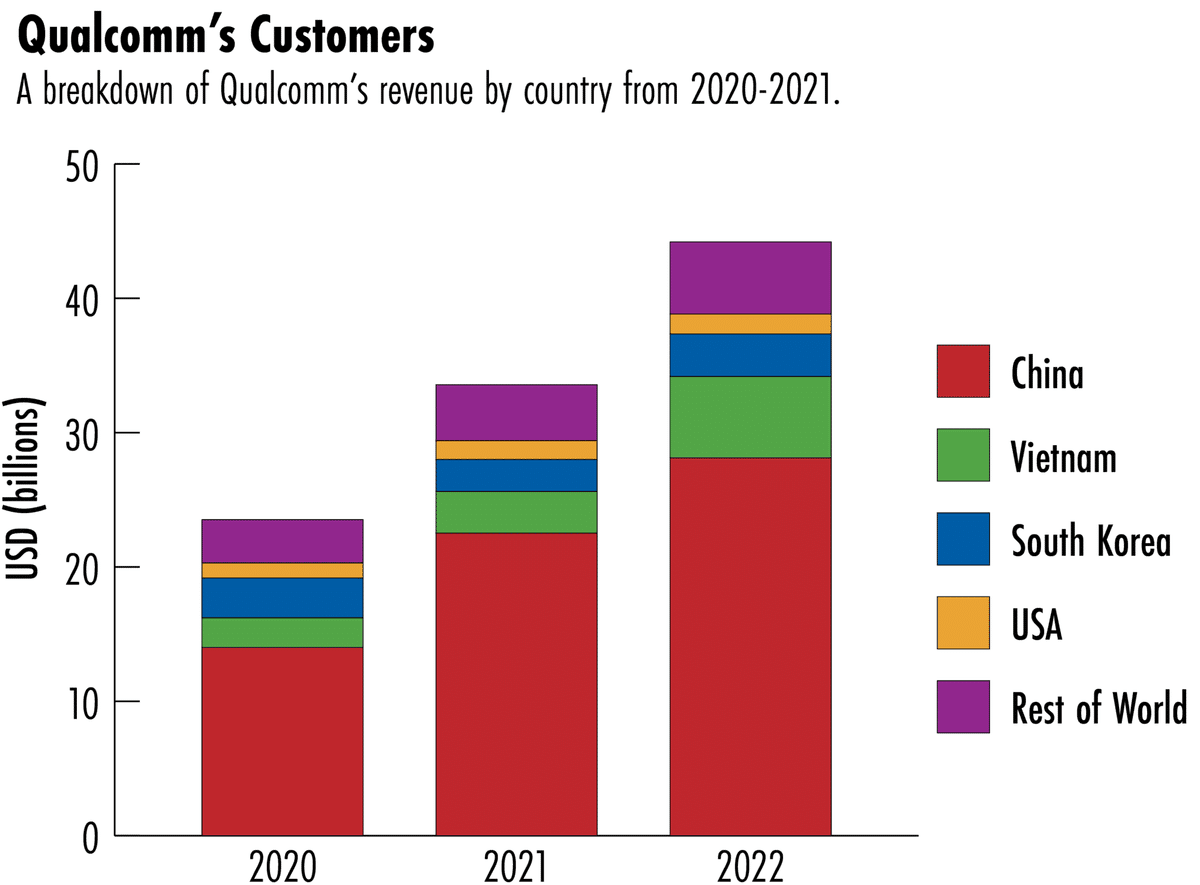

Note: Figures for China include Hong Kong. Data: Qualcomm’s 10-k

Especially China’s: the People’s Republic accounts for a third of Qualcomm’s $44 billion in annual revenue. It is not only the largest handset market in the world, with 1.2 billion mobile subscribers, but also home to four of the world’s largest smartphone manufacturers: Xiaomi, Lenovo, Vivo and OPPO — all of which rely on Qualcomm’s intellectual property.

“The view in China is that Qualcomm is still the premium product,” says Daniel Nystedt, a Taipei-based chip analyst with TriOrient Investments. “And Qualcomm is involved in every aspect of mobile communications, from working closely with governments on the right spectrum to use, to basebands and network buildout, and more. That makes them sticky from a top-down level.”

Indeed, Beijing is kind of stuck with Qualcomm at the moment — even though it would rather not be. As Martijn Rasser, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, notes, “President Xi has been crystal clear that he wants Chinese companies to dominate the Chinese market.” Homegrown champions like Huawei and ZTE have been crippled by U.S. sanctions, but Rasser says circumstances for Qualcomm could still change in the flash of a radio wave.

“Any American company that has staked the Chinese market as their source for sales and revenue growth should really be rethinking those projections,” he says.

Apple, Qualcomm’s longtime rival and lucrative client, seems to be. Although the company’s chief executive, Tim Cook, was also present at last month’s China Development Forum, Apple is reportedly making moves to diversify its manufacturing outside of China and focusing on growing its sales elsewhere.

Qualcomm, by contrast, seems to be leaning into a newly reopened China and recently announced heavy investments in China’s fast-growing automotive sector.

“Qualcomm is not backing away from China,” says Daniel Ives, a semiconductor analyst with Los Angeles-based Wedbush Securities. “They’re well aware of who butters their bread.”

Yet Qualcomm’s sunny optimism in China obscures a darker reality. As an American chip champion, the company is surely “on the list of first-strike targets” if Beijing were to retaliate against U.S. sanctions, says Jay Goldberg, a chip consultant and former Qualcomm senior director who worked in China. The company’s $150 million or more*3 of investments in China — managed through its venture capital arm, Qualcomm Ventures — might also be affected if the Biden administration imposes restrictions on outbound investment, which it is keen to do.

(*3 A Qualcomm representative says the company does not break down investments by country.)

“I think it is unlikely that the U.S. government will make anyone divest previous investments,” Goldberg says. “But beyond that I would worry a little bit. Will China let American VCs take money out of the country? Will China-based VC funds be allowed to invest in U.S. companies?”

Qualcomm put itself in the position of playing politics in China with how they got started… They’re on good terms with the Chinese government now. But they certainly remember when they weren’t.

Qualcomm declined to comment on its China business. But while most companies would likely bristle from this kind of geopolitical squeeze, Qualcomm seems to relish it. The company, after all, got its big break under similar circumstances more than two decades ago, and it’s been used as a “pawn” in the U.S-China relationship numerous times since.

“Qualcomm put itself in the position of playing politics in China with how they got started,” Goldberg says. “They entered the political game back in the ’90s and have remained in it over the years. They’re on good terms with the Chinese government now. But they certainly remember when they weren’t.”

Indeed, if any company has the standing and the stomach to navigate the current U.S.-China relationship, it is likely the firm that both sides can’t do without.

DIALING IN

Qualcomm’s supremacy rests on CDMA — “code-division multiple access” — a telecommunications technology that uses a “spread-spectrum” technique to allow several transmitters to send data over a single communication channel. This allows for more simultaneous, higher quality telephone calls.

There is some debate around who invented CDMA; like the Internet, cellular communication was created for U.S. defense purposes. But Qualcomm’s innovation with CDMA was two-fold. First, it adapted the technology for satellite and mobile cellular use. And second — and more importantly — it commercialized CDMA.

Qualcomm’s founder, Irwin Jacobs, embodies the nerd-shark ideal. David Robertson, a veteran telecom engineer with Analog Devices, calls him “part Jobs, part Wozniak,” meaning part expert marketer, part master inventor. “He’s a hall of famer,” says Robertson.

Jacobs, now 89 years old, was an engineering professor at M.I.T. and then the University of California, San Diego, before he joined the corporate world. In San Diego in the early 1980s, he ran a technology company called Linkabit, which dealt mostly in satellite communication and defense contracting. (San Diego is a Navy hub.)

He founded Qualcomm in 1985 alongside six others hoping to capitalize on a rapidly expanding portfolio of telecom patents, including their improved-upon CDMA. The competing wireless standard at the time, a European invention called GSM, was qualitatively inferior. Still, because it arrived first, GSM boasted overwhelming market share in Europe and America.

China, however, remained contested. The country was just starting to patch together a cellular network, which meant it represented an immense opportunity to showcase Qualcomm’s CDMA. By the early 1990s, Qualcomm had pioneered CDMA-based networks in Hong Kong, Brazil and South Korea, and Jacobs told colleagues that he was “cautiously optimistic” about gaining market share in China.

For the young firm, the stakes were high.

“They felt that CDMA would not be able to go mainstream and become the global standard if they didn’t break into a market like China,” says Dave Mock, author of The Qualcomm Equation, a book on Qualcomm’s first two decades.

Jacobs first visited China in 1992, when it was beginning its push for entry into the World Trade Organization, and he developed a personal affinity for the country.

“It was his pet,” says Dennis Fu, a former Qualcomm senior engineer who helped lead the firm’s early forays there. Jacobs was particularly fond of Beijing street markets, Fu recalls, and once, on a pre-Christmas visit, bought 20 marble globes.

But Nokia and Ericsson — the GSM champions — weren’t going to give up China easily. With European government support, the two firms convinced China’s two largest telecom operators, China Mobile and China Telecom, to adopt GSM. Qualcomm hoped to hoist CDMA onto the remaining giant, China Unicom.

“Dealing with Ericsson and Nokia were among our biggest challenges,” recalls David Hind, a former Qualcomm vice president in China. “They really were the enemy.”

CDMA, Qualcomm knew, was a superior technology to GSM. It was able to process more bandwidth and ensure higher-quality calls across longer distances. But negotiations between Qualcomm and the Ministry of Postal and Telecommunication, the precursor to today’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, had stalled because “the Chinese government insisted that Qualcomm transfer technology designs, and Qualcomm refused,” Fu says.

The California firm had another powerful card to play, however: the U.S. government.

As Beijing navigated drawn-out negotiations with Washington over joining the W.T.O., Qualcomm pressed the U.S. government to make CDMA adoption a precondition. Eager to see a homegrown telecom company take on the European competition, heavyweights like U.S. Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky, Commerce Secretary Bill Daley and Clark “Sandy” Randt, Jr., the U.S. ambassador to China, all battled for Qualcomm.

“They were huge influences,” Hind says. “When the Bush government would come over [to China] Sandy would make sure that CDMA was on the agenda when they talked to high government officials.”

Qualcomm also coaxed Brent Scowcroft onto its board. A two-time U.S. National Security Advisor with a deep history in China, Scowcroft would often join Jacobs on regular visits to Beijing to meet officials.

But despite this political leverage, Qualcomm still had to convince CCP apparatchiks that CDMA was indeed superior to GSM, which was being heavily promoted by European governments through Nokia and Ericsson.

There are not many companies that can be thought of as a poster child for innovation. You think of Ford, General Electric, Hewlett-Packard. Qualcomm definitely fits that mold.

“The EU was pushing stories about CDMA technology being used to potentially do all kinds of bad things to China,” says Perry LaForge, a former Qualcomm executive who ran the CDMA Development Group, an advocacy body.

To win over officials, Qualcomm arranged a CDMA demonstration in Tianjin, a major city outside Beijing, in 1994. The company shipped in base stations and other equipment from abroad and, to test voice quality at different speeds and distances, rented a dozen vehicles to drive around the city.

“We worked very hard because we knew it was so important for Qualcomm to get the China market,” Fu recalls, adding that the Qualcomm engineers had “a sense of mission.”

The demonstration proved what Jacobs knew it would. But internal politics within Chinese officialdom and diplomatic crises such as the inadvertent U.S. bombing of a Chinese embassy in Belgrade, in 1999, kept dragging out the decision.

Then, in an October 2000 meeting between China Unicom and Qualcomm, with Jacobs present, prime minister Zhu Rongji insisted that China Unicom finalize a deal, resolving the matter. Zhu had reportedly felt “exasperated” by the drawn-out negotiations. China Unicom would use CDMA for its cellular networks, and other mobile providers soon followed. According to Hind, it took some seven years for CDMA to fully replace GSM in China.

“What Qualcomm did in China is a success story, starting from the very beginning,” Fu says.

That success kicked off Qualcomm’s rapid ascent to global domination. “Instead of knocking on doors and asking for trust, it was now mainly trying to keep up with demand,” writes Mock in Equation. Qualcomm’s stock swelled by 25 times leading up to the China Unicom deal, soaring from just under $7 in 1999 to $176 by the year’s end. And its fusion of extraordinary engineering with impeccable business sense cemented Qualcomm’s position in the hallowed halls of American ingenuity.

“There are not many companies that can be thought of as a poster child for innovation,” Mock says. “You think of Ford, General Electric, Hewlett Packard. Qualcomm definitely fits that mold.”

Qualcomm had begun its business in China with a battle against strong European competitors. They won, in large part, due to the foresight of what kind of product the market ultimately wanted. What they didn’t foresee was that, with a stronger China, came a harder set of problems.

CUTTING OUT

With offices in Shanghai and Beijing, Qualcomm entered the new millennium on a high note. Eager to cement their position in China, they set up training workshops for Chinese engineers and donated to Chinese institutions — all while increasing their sales.

But, in a prelude to the U.S.-China turmoil to come, the honeymoon ended when Chinese companies started getting the bill.

As subsequent cellular generations developed, like 3G, 4G and 5G, CDMA remained the base technology. Because of this, firms in China and elsewhere remained dependent on Qualcomm’s IP through each evolution — a dependency that generated significant resentment.

For developing economies, royalty costs to Qualcomm could be gargantuan. In South Korea, for instance, Samsung and LG’s royalty payments to Qualcomm reached a sum so high in the early 2000s that it appeared in the South Korean balance of payment statistics.

As China’s own handset firms began to grow, some simply refused to pay up. By the early 2010s, Qualacomm executives said the company was missing out on billions worth of fees from the country.

Tensions came to a head in 2013, when the National Development and Reform Commision announced that it had opened an anti-monopoly probe into Qualcomm’s business practices in China — “negotiation with Chinese characteristics,” quips Goldberg.

In 2015, Qualcomm agreed to pay a $975 million fine, the largest Chinese anti-monopoly fine ever, and offered Chinese companies a lower royalty rate. Qualcomm also agreed to open R&D and training centers at Chinese universities; launched a new partnership with SMIC, the Chinese chip manufacturer; and opened a $150 million China Investment Fund.

Soon after, the company announced a $280 million joint venture with the Guizhou provincial government to build data center CPUs. In attendance at the signing ceremony was Chen Min’er, now a high-ranking Politburo member. The company also opened an “Innovation Center” in Shenzhen, a Chinese tech hub, to help “in improving Shenzhen’s core competitive strengths.”

In 2017, on the eve of Trump’s state visit to Beijing, Qualcomm signed three deals with Chinese handset makers worth $12 billion. And in retrospect, observers say, Qualcomm’s tense crescendo in China resolved into a relative win-win.

“Qualcomm got back in the good graces of the Chinese government,” says Goldberg, who worked on the Guizhou joint-venture. “They had a much better relationship from then on.”

But stateside, new sparks were alighting. The Trump administration had launched its opening attacks in the trade war, enmeshing Qualcomm once again in sensitive geopolitics. After sanctions were placed on ZTE and Huawei — two big customers for Qualcomm — the Chinese side responded.

In 2018, Qualcomm was trying to acquire NXP, a Dutch chipmaker with significant business in China. Chinese regulators had to sign off on the deal for it to go through, but through inaction, Beijing essentially refused to do so.

“They didn’t officially deny it; they just sat on it for 20 months,” says Stacy Rasgon, a veteran industry analyst with Bernstein Research. “Then China had the nerve to say, ‘We didn’t say no! We’re still thinking about it. Maybe we’ll still approve it.’”

In 2018, Qualcomm scrapped the $44 billion deal, leading some to say that the NXP acquisition was a “pawn” in the trade war. But Beijing wasn’t the only one playing chess.

Following some internal problems, including fears the firm was overspending alongside a fierce and expensive legal battle with Apple, Broadcom Inc., another leading chip designer that was based in Singapore at the time*4, launched a hostile takeover of Qualcomm. But in March 2018, after a CFIUS review, President Trump’s Treasury Department blocked the acquisition on national security grounds.

(*4 In the midst of the takeover attempt, the firm re-domiciled in America. Trump himself announced the relocation in a celebratory press conference, calling Broadcom “one of the really great, great companies.”)

“There is credible evidence that leads me to believe that Broadcom… might take action that threatens to impair the national security of the U.S.,” Trump wrote in his order.

It’s unclear, however, what that evidence was. The general rationale seems to be that Broadcom may have gutted Qualcomm and cut R&D, thus weakening a U.S. company in a critical industry, and that Broadcom’s China ties were too suspicious. John Shu, an attorney who served in both Bush administrations, argued in an essay in Federalist Society, a conservative non-profit, that Trump’s decision was warranted because Broadcom’s deal involved a California private equity fund called Silver Lake Partners, Ltd, that “often works with billions of dollars from China.” (Silver Lake declined to comment.)

Whatever the precise reasoning for the block, the tense geopolitics worked in Qualcomm’s favor once more.

EDGE CASE

For the time being, at least, Qualcomm seems to have it all: the support of both the U.S. and Chinese governments. It is even diversifying within China, investing heavily in what it calls “edge” technologies such as artificial intelligence and “smart” cars. (Qualcomm gestures at this rather vague category in a recent promotional film wherein Michelle Yeoh blows up an SUV.)

“It’s not going to be all handsets forever,” says Rasgon, of Bernstein Research. “Their automotive business in particular could get quite sizable in a few years.”

Recently, Chinese EV makers Li Auto and Geely have promoted the fact that their cars use Qualcomm chips. Qualcomm is also partnering with the Chinese automaker Great Wall Motors on autonomous driving as well as Baidu on an electric vehicle project.

The moves underscore that China, for the moment, still needs the American chip champion. Indeed, earlier this month Beijing, citing national security concerns, opened a probe into Micron Technology, another leading U.S. semiconductor firm, causing Micron’s shares to plummet; like Qualcomm, a large portion of Micron’s revenue — about a quarter — is derived from China. Many interpreted the move as payback for a recent suite of U.S. chip sanctions, and theoretically, Beijing could just as easily target Qualcomm.

But it likely won’t.

“If China bans Qualcomm chips today, ultimately, the Chinese will suffer,” says Sravan Kundojjala, a China-focused semiconductor analyst with Ottawa-based TechInsights. “There is no alternative, especially in 5G.”

Beyond outright bans, though, there are other ways Beijing could enact a bruising. Regulators, for instance, might demand that Qualcomm reduce or scrap altogether its infamous royalty fees.

“Companies in that position feel pretty defenseless,” says Miller, the Tufts historian. “That’s a position where you don’t have recourse or credible courts. That’s one area in which Qualcomm would be vulnerable if Chinese regulators decide to punish them.”

Beijing is also making longer term moves to edge Qualcomm out — albeit bureaucratically.

Ever since 1865, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) has helped set the standards for the telecom industry. It, alongside other bodies around the world, is where engineers and officials decide which cellular technologies become national and global technical standards, and where they mandate mutually compatible hardware and software to ensure reliable communications. (5G, for instance, has over 1,200 technical specifications.) The West has always dominated these bodies, and in the digital age, Qualcomm has been its major star.

But for decades, China has been working hard to increase its influence in global standards bodies*5, an ambition embodied in Beijing’s Standards 2035 initiative. To do this, Beijing has been investing heavily in standardization development at home, submitting large amounts of patents to the bodies for consideration and gaining leadership positions for Chinese officials within those bodies.

(*5 Major telecom standards bodies include the ITU, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology, the 3rd Generation Partnership Project and the European Telecommunications Standards Institute.)

“Qualcomm is the case study for why Chinese authorities became focused on standards and the implications of that,” says John Lee, director of East-West Futures. “You can draw a straight line from Qualcomm to the stronger efforts that were made by Huawei, with support and encouragement from the Chinese government, to play a greater role in setting standards for 5G.”

Several Chinese patents, especially ones designed for 5G, have already been adopted and implemented in telecom — and more are likely, says Tim Ruhlig, who studies China’s standardization efforts for the German Council on Foreign Relations. “China is large so it sends plenty of people to these bodies, and it’s submitting tremendous amounts of contributions,” he says.

The patent proposals from China come from an ecosystem that simply cherishes other values, that sets different priorities. Technology is never value-neutral.

It will be years before these contributions significantly reduce Qualcomm’s influence, but Western security experts still worry about the implications of adopting Chinese telecom standards en masse. This was a key driver behind U.S. concerns about Huawei, for instance. Such technologies could potentially be used for spying or other nefarious state means, experts say. Their adoption could also create economic dependencies on China that could be used as leverage in other arenas — not unlike the dependence on Qualcomm that Washington nurtured with China during W.T.O. negotiations.

“The patent proposals from China come from an ecosystem that simply cherishes other values, that sets different priorities,” Ruhlig says. “Technology is never value-neutral.”

No matter how much Qualcomm might wish it to be. As Amon made clear in Beijing, Qualcomm remains “committed to providing our partners…with the most comprehensive and advanced solutions to enable a thriving digital economy.” But the more China’s economic might grows, the less dominant Qualcomm’s position there may yet become.