U.S.-Japan Critical Minerals Agreement, CRS, Jan. 8, 2025.

On March 28, 2023, the United States and Japan signed a

critical minerals agreement (CMA) covering five key

minerals related to the production of batteries for clean

vehicles (commonly referred to as electric vehicles or

“EVs”). The U.S.-Japan CMA entered into force

immediately upon signature.

The CMA seeks to address Japan’s concerns regarding

certain content requirements for the consumer tax credit for

new EVs included in P.L. 117-169, known as the Inflation

Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA requires a certain

percentage of critical minerals in EV batteries to be sourced

from the United States or U.S. free trade agreement (FTA)

partners. Congress has approved all previous U.S. FTAs via

legislation and typically set FTA procedures and

requirements in Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), which

expired in 2021. The United States and Japan do not have a

congressionally approved FTA, but the U.S. Department of

the Treasury has designated the CMA as an FTA for the

purposes of the IRA EV tax credit.

The U.S.-Japan CMA ties into a broader discussion about

congressional and executive trade authorities. Other issues

for Congress include implications for U.S.-Japan trade

relations, ongoing and future CMA negotiations, and the

implementation of the EV tax credit.

IRA EV Tax Credit

The IRA provides consumers a tax credit of up to $7,500

for new EVs (26 U.S.C. §30D). To qualify for the tax

credit, EVs must meet overall requirements, including final

assembly in North America and retail price caps. U.S.

policymakers crafted IRA EV tax credit requirements that,

in part, reflect concerns over U.S. dependence on the

People’s Republic of China (PRC, or China). China

dominates the EV supply chain, including mining and

processing of critical minerals and production of EVs and

EV batteries. EVs can qualify for partial credit if they meet

content requirements related to the components or critical

minerals in the EV battery. Specifically, as of January 2025,

the $3,750 critical minerals-related portion of the credit

requires 60% by value of an EV battery’s critical minerals

to be sourced from the United States or a U.S. FTA partner.

The requirement will increase annually until reaching 80%

in January 2027.

In addition, starting in January 2024 and January 2025,

respectively, EVs cannot qualify for the credit if they

contain battery components or critical minerals from

“foreign entities of concern” (FEOC), which includes

countries such as Russia and China. Treasury and the U.S.

Energy Department have defined FEOC to include all

entities headquartered in or organized under the laws of an

FEOC country. The guidance indicates that FEOC-tied

operations in the United States and FTA partner countries

as well as arrangements such as licensing agreements could

be either IRA compliant or noncompliant, depending on the

specific corporate situation. The guidance includes a

transition rule that provides flexibility until 2027 for certain

low-value critical minerals, including graphite, that may be

difficult to trace through the supply chain under current

industry standards. China is the top global producer of

graphite. Since December 2023, the PRC government must

approve graphite exports.

FTA Partner Provision and CMA Negotiations

There is no statutory definition for an FTA, but under

World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, a regional trade

agreement such as an FTA must cover “substantially all

trade” between trading partners. The United States currently

has 14 such “comprehensive” FTAs—authorized and

approved by Congress—with 20 countries. During the

Trump Administration, the United States and Japan signed

the 2020 U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA), which is

not a comprehensive FTA. It reduces tariffs on some goods,

but not those in the automotive or critical minerals sectors.

Automotive industry groups and some U.S. trading partners

have expressed a desire for allowing more trading partners

to qualify for the FTA partner provision. They argue that it

will be difficult to source adequate supplies of critical

minerals from the United States and its comprehensive FTA

partners within the outlined timeframe. The Biden

Administration proposed new trade agreements focusing on

critical minerals in EV batteries as a method of addressing

such concerns. The U.S.-Japan CMA was the first such

agreement to be concluded. Currently, the United States is

negotiating CMAs with the European Union (EU) and the

United Kingdom (UK). In November 2023, the United

States and Indonesia agreed to develop a “critical minerals

action plan” with a view toward future CMA talks.

U.S.-Japan CMA Overview

As of 2023, Japan is the sixth-largest U.S. trading partner

(goods and services). The automotive sector plays a major

role in the U.S.-Japan economic relationship. In 2023, the

United States imported $54.5 billion in vehicles and parts

from Japan and exported $2.5 billion to Japan. Since 1982,

Japanese automakers have invested $61.6 billion in U.S.

manufacturing facilities, and have announced various

investments in EV and EV battery production following the

passage of the IRA and the 2020 United States-Mexico-

Canada Agreement (USMCA), which has North American

content requirements for duty-free automotive trade.

The U.S.-Japan CMA changes neither U.S. law nor existing

tariffs, and does not include other market access provisions.

The United States and Japan stated that the CMA’s

objective is to “strengthen and diversify critical minerals

supply chains” and promote the adoption of EV battery

technologies. The critical minerals covered by the CMA are

cobalt, graphite, lithium, manganese, and nickel—all key

EV battery inputs. Among other measures, the United

States and Japan agreed to (1) maintain the “current

practice” of not imposing export duties on critical minerals

trade between their countries; (2) confer on measures to

address nonmarket policies and practices affecting critical

minerals supply chains; (3) confer on best practices for

review of foreign investments in their countries’ critical

minerals sectors; (4) coordinate on actions related to forced

labor and other labor rights connected to critical minerals

supply chains; and (5) promote employer neutrality related

to unions. The two countries agreed to review the CMA

periodically to determine whether to terminate or amend the

CMA, including which critical minerals are covered.

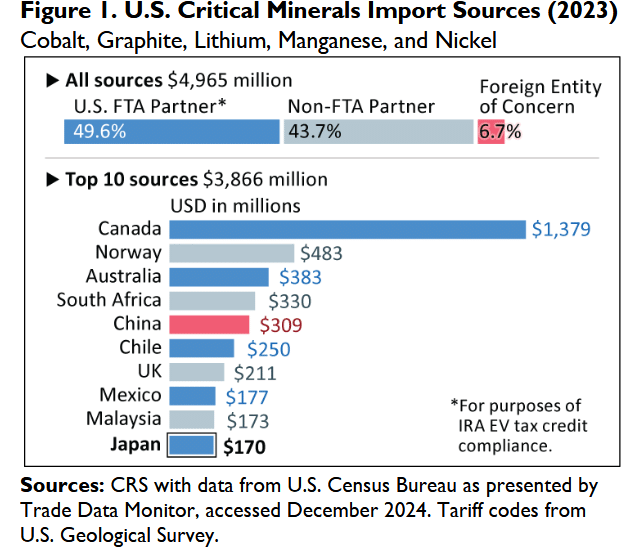

Japan is not a large source of mined critical minerals but

possesses related capabilities, including mineral processing

and EV battery production (e.g., Panasonic). In 2023, Japan

was the tenth-largest source of U.S. imports of the five

covered critical minerals (see Figure 1), particularly

processed cobalt.

Stakeholder Reactions to the CMA

Japanese automakers praised the CMA as recognition of

Japan’s status as a key U.S. ally and trading partner. The

International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and

Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW)—a

major U.S. union representing workers at Ford, General

Motors, and Stellantis—expressed skepticism about the

CMA, noting that U.S. imports of Japanese critical minerals

are relatively small, and the inclusion of Japan as an FTA

partner could give “incredibly competitive” Japanese

automakers a pathway to receive U.S. subsidies. Some

Members of Congress raised concerns about the CMA’s

lack of binding or enforceable commitments, particularly

related to labor and the environment. Some Members also

criticized Treasury’s designation of the CMA as an FTA for

the purposes of the EV tax credit, describing this action as

overriding congressional trade authorities and undermining

Congress’s intent to build up domestic EV supply chains.

Issues for Congress

U.S.-Japan FTA and congressional trade authority.

Some Members and industry groups continue to push for a

comprehensive U.S. FTA with Japan (e.g., further USJTA

negotiations or joining the Comprehensive and Progressive

Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership [CPTPP]).

Members may consider whether targeted agreements like

the CMA are appropriate substitutes. A related issue is

Congress’s role in trade agreements. During the 118th

Congress, some Members proposed legislation defining

FTA for the purposes of the tax credit as a congressionally

approved agreement covering “substantially all the trade”

between the United States and one or more countries (e.g.,

H.R. 7983). Other Members proposed legislation to

authorize the negotiation of and outline approval processes

for limited FTAs focusing on critical minerals (S. 5451).

See CRS Report R47679, Congressional and Executive

Authority Over Foreign Trade Agreements.

Future CMAs and other critical minerals initiatives. It is

unclear whether the U.S.-Japan CMA will be a template for

other CMAs. Some critical mineral-rich nations without a

comprehensive U.S. FTA (e.g., Argentina, Norway, the

Philippines) have expressed interest in qualifying as FTA

partners through CMAs or existing trade initiatives. The

United States is also engaged in plurilateral initiatives such

as the Minerals Security Partnership, which convenes

governments and private companies to discuss critical

minerals projects. Some Members of Congress have

expressed interest in pursuing additional CMAs and/or

strengthening critical minerals supply chains with key

partners (e.g., S. 3631, 118th Congress). At the same time,

some Members also have concerns about concluding CMAs

with countries, like Indonesia, due to weak labor and

environmental standards, PRC investment ties, and

restrictive trade practices. Other issues include the

durability of CMAs and how CMAs and other critical

minerals frameworks relate to existing U.S. trade initiatives.

IRA EV tax credit implementation. Some Members

argued that the Biden Administration’s implementation of

the credit (e.g., temporary flexibility for certain minerals

and interpreting FEOC to possibly allow for materials from

PRC-tied firms) undermines congressional intent and may

allow U.S. taxpayer funds to flow to PRC firms. Others

supported the Administration’s efforts to balance between

derisking supply chains and promoting EV adoption.

During the 118th Congress, some Members proposed

legislation to change or further clarify IRA EV tax credit

requirements (e.g., S. 3869, S. 756/H.R. 2951, H.R. 3938,

H.R. 7980). Some Members also proposed eliminating the

EV tax credit (e.g., S. 4237). Congress may also consider

oversight of the EV tax credit’s implementation—for

example, during the 118th Congress, some Members

pursued a Congressional Review Act resolution (e.g.,

S.J.Res. 87/H.J.Res. 148).

Kyla H. Kitamura, Analyst in International Trade and

Finance

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12517