China investment limits are dividing the Biden administration, Semafor, Dec 16, 2022.

Liz Hoffman, Louise Matsakis, and Morgan Chalfant

The White House has drafted a plan to keep American money out of sensitive Chinese tech companies. But Treasury officials, who are fielding concerns from big business and financial firms, have been pushing to narrow it.

The Biden administration has been working on an executive order that would restrict outbound investment from the U.S. into key high-tech industries in China, like quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and semiconductors, Semafor reported in September. At the time, the order was expected to be announced within a few weeks, but the process has been delayed further and may push into next year, people familiar with the matter said.

A key roadblock, the people said, is Treasury, which would have a role in implementing any proposed rules. The department chairs a panel, known by its acronym, CFIUS, that reviews inbound foreign investments in U.S. companies. It also maintains investment blacklists of sanctioned entities and foreign nationals that are off-limits to U.S. firms.

One idea government officials have floated is restricting investment to companies not only based in China, but that also have Chinese founders, one person familiar with the matter said. That would prevent U.S. firms from funding startups founded by Chinese nationals who graduated from U.S. universities or have long work histories in the country.

Paul Rosen, the assistant Treasury secretary overseeing CFIUS and investment security, has been meeting finance and business executives in New York, Boston, and other corporate and financial hubs in recent weeks, one of the people said. He has heard concerns from multinational companies that rely on Chinese suppliers or consumers, as well as asset managers with existing investments on the mainland.

Some of the firms that have spoken with government officials include BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, private-equity shop KKR, and venture firm Sequoia, whose China arm just raised a $9 billion fund that, as Semafor has reported, helped spark the White House’s concerns in the first place.

The White House and Treasury did not respond to requests for comment. The companies either declined to comment or didn't return requests for comment.

Louise's view

The Biden administration is trying to shine light on an important blind spot in its Chinese foreign policy: it doesn’t really know where American capital is flowing to in the People’s Republic.

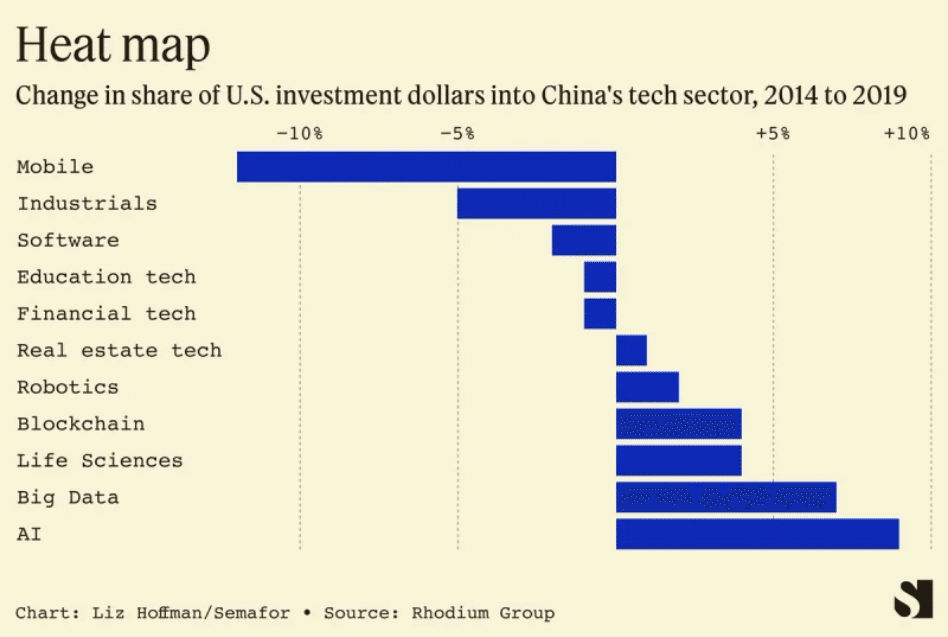

China’s tech industry boomed in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, and U.S. firms poured billions of dollars into the country’s artificial intelligence startups, e-commerce and ride-hailing services, social media platforms, and other businesses. When relations between the U.S. and China were still rather rosy, these investments were just part of a modern globalized economy.

But it turns out that some of the money went to Chinese firms in sectors the Biden administration has determined have ties to the Chinese military, or otherwise pose security and economic risks to the U.S., most notably computer chip manufacturing and AI. Identifying those investments and figuring out what to do about them — especially without creating significant collateral damage — is not going to be easy.

The White House’s executive order would be the second major attack on China’s tech sector over the last few months. In October, the U.S. government haphazardly introduced sweeping export controls on advanced semiconductors and equipment sent to China that sent businesses scrambling.

This time, it looks like the Biden administration is taking a more focused and narrow approach, and has spent a long time listening to U.S, businesses about what negative impacts restricting their Chinese investments could have. But targeting Chinese entrepreneurs in the U.S. would be an enormous mistake and disincentivize valuable talent from coming to America.

Room for Disagreement

Critics say that the White House’s anti-China agenda risks going too far, and could wind up backfiring.

“Americans and others may soon find themselves experiencing carelessly broken supply chains and a fracturing economic order,” wrote Jon Bateman, a senior technology and international affairs fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in Politico. “They could face slower innovation, higher inflation, rockier trade among friendly nations, and spiraling instability with an emerging Asian superpower.”

The View From The Hill

Hawkishness toward China is as bipartisan an issue as you can find in Congress, so it’s surprising that this is being done through an executive order, which could easily be rescinded by subsequent presidents.

But congressional gridlock gets in the way even of bipartisan priorities. “Ideally, we would do this through legislation as opposed to the executive order, and it doesn’t look like that’s going to happen,” Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, told Semafor.

The View From Taiwan

Taiwan already regulates outbound investment in high-tech sectors, particularly semiconductors, an industry in which it is a global leader. The Taiwanese government is currently reviewing Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.’s announcement last week that it will invest $40 billion in a new chip plant in Phoenix, Arizona.

Taiwan, and in turn TSMC, the country’s national treasure, have been under pressure from U.S. officials to align with Washington’s anti-China agenda. But opening a factory in Arizona, where costs are significantly higher, “has triggered mixed and polarized responses,” wrote Colley Hwang, the president of DigiTimes, a Taiwanese semiconductor industry publication.

Notable

In another move designed to curb China’s tech power, the Biden administration today blacklisted dozens of Chinese tech companies, including one of the country’s top chip producers.

Earlier this week, Beijing filed a dispute with the World Trade Organization over the White House’s October chip export controls.

Sequoia China reportedly employed the daughter of one of China’s top political leaders for years, The Information reported in September. The story, which echoes the “princelings” scandal of early-2010s Wall Street, exemplifies the types of concerns Washington has about U.S. investment in China.