Backgammon - An Abacus Game! by Alexander Auer

This literature shown below is written and posted by Alexander Auer on his facebook page on 2021/2/12 It is translated into Japanese ->https://note.com/bgmochy/n/n7ee63ec6bc8f

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About 2 years ago I published my study on the origin of backgammon and the etymology of the name. In this new version I have added some more findings. I hope you enjoy reading it and I would appreciate your feedback.

Backgammon - An Abacus Game!

If you are interested in the etymology of the word "backgammon", you will usually find the following explanation:

The game was named in the English-speaking world, it was a composition of the words "back" for "behind" or also "back" and "gammon", for game, originating from the medieval form "gamen".

This name is said to come from the fact that hit checkers had to be replaced at the end of the game, or from the fact that there were variants that started without a fixed placement of the checkers. The checkers had to be brought into the game by rolling the dice first, at the end.

I always found these explanations very trivial, they are not a unique selling point, and to me the game of backgammon just seems too perfect that such trivialities could have led to the naming of the game.

That's why I started to search, and searched countless sources. I found incredibly exciting connections that have never been discussed before.

We all know the supposed development of modern backgammon from the ancient Egyptian game "Senet" to the Roman "Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum", the twelve-line game to the Roman Tabula, which then arrived in the area of today's Great Britain as "tables". The relationship of the "Senet" to backgammon is also strongly doubted, and rightly so.

I was first interested in how people calculated and counted in the first place about 5000 years ago, and this introduction proved to be correct and became the key to my understanding of backgammon.

The decimal system as we know it today was unknown, as was so-called abstract arithmetic, also called Hindu-Arabic arithmetic. People at that time used the sexagesimal system, a base 60 arithmetic system.

This was developed by the Sumerians, a people in the area of today's Iraq. The Sumerians developed this number system based on observations of the stars. They had 7 main gods, the sun and moon, and the planets Jupiter, Saturn. Venus, Mercury and Mars. This is incidentally why we know 7 days a week. These planets were visible to the naked eye and stood out clearly from the fixed stars in size and luminosity. In developing their calendar, the Sumerians aligned their two slowest gods, Saturn and Jupiter, which take 30 and 12 years respectively to pass through the zodiac. The smallest common multiple is 60! The product of both numbers is 360, and this is the reason why a circle is divided into 360 degrees, until today. Dividing the Zodiac into 360 degrees means that Jupiter moves 30 degrees per year and Saturn moves 12 degrees. The Sun takes one year to pass through the Zodiac, Jupiter does 1/12 in that time, which is why the Sumerians divided the year into 12 months. The sun then passes the same distance in a month as Jupiter does in a year. And since the sun travels 30 degrees of the zodiac in a month, the Sumerians divided the month into 30 days. The sun moves one degree per day. Of course, the Sumerians knew that the year has 365 days, and therefore they developed feast days at the end of the year, which, by the way, were adopted by the Egyptians, and are also celebrated to this day, packaged as religious holidays.

The Sumerians were fascinated by the thought that their 7 (sun, moon=2, and 5 planets) gods were reflected in the fact that man has 2 hands with 5 fingers each. And they were fascinated by the fact that their wonderful number 60 has so many divisors, but just not the 7, which is a prime number.

Now back to the game...

This sexagesimal system was in use in Mesopotamia, in everyday life the "little sister", the duodecimal system to the base 12, was sufficient. With it the fingers were used to calculate in such a way that the thumbs served as pointers and the remaining four fingers with 3 limbs each as counters to 12.

This calculating system was used at least from 2500 before Christ on so-called calculating boards, even on tables, which were manufactured for this purpose.

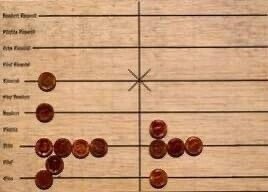

One of these boards, the "Salamisian board" was found near Athens in 1846, and was probably still in use around 500 BC. These arithmetic boards had vertical lines on which small stones were placed as counters. The lines themselves often had units on them. With the Romans for example for ones, fives, tens, fifties, hundreds and thousands (6 lines), the whole mirrored again, in order to be able to accomplish easily additions and subtractions.

By the way, the little stones were called "calculus" in ancient Rome, which is where our word "calculation" comes from. Also, already in ancient Egypt, coins were used instead of pebbles.

Who used these boards? Well, it was rulers, merchants and architects, people who were usually educated and had extensive knowledge of mathematics.

These pebbles or coins were moved on the vertical lines to perform arithmetic operations, even complicated angle functions and root calculations were possible. In essence, these arithmetic boards worked on the principle of the abacus.

I was very fascinated by the fact that the Greek writer Herodotus describes in his travel diary about 450 BC his amazement that the Greeks move their pieces from left to right, but the Egyptians from right to left!

From here on it is easy to imagine how Greeks and Egyptians met and put their boards together. All that was left was for someone to put dice "in play" and you had a backgammon board! The fact that backgammon was originally played with 12 checkers, as was probably the twelve-line game later, seems almost inevitable, because of the sexagesimal system, or rather the duodecimal system. “Calculation on lines", as this form of arithmetic is called, would also explain why the Romans called their game the "12-line game", and not the "12-square game".

From all these observations, I am deeply convinced that backgammon or its predecessors, were not invented as a game, but developed from an everyday object of use. The boards, which were actually developed for mathematics, have been abused, so to speak, to have fun. And this not by uneducated people, but by people who had a high level of knowledge in mathematics.So I think that backgammon was played very early on a very high mathematical level, and only later degenerated into a game of chance, when it became common property.

Before I get to the etymology of the word backgammon, I would like to outline how strictly the game follows the sexagesimal system, and therefore the descent from abacus is highly probable:

The sexagesimal system is built on the number 60, which is the least common multiple of 12 and 30. We have 30 checkers and 2x12 squares on the backgammon board. The divisors of 60 are 1,2,3,4,5,6,10,12,15,20, 30 and 60. This enormous number of divisors made the system mathematically so attractive, in everyday life as a system of twelve. The checkers in backgammon are placed on the beginning, middle and end of the 12 (on the 1, the 6 and the 12).

Since old forms of the game were probably played with only 12 checkers, I think that the three checkers on the 8 were added later. Possibly already in "Tabula", which was then played with three dice, an attempt was made to make the game more complex, but the three dice contradict the strict logic and probably therefore disappeared again, so that it was played with 2 dice. Two dice have 12 numbers, which makes the game coherent again. Adding more stones seemed to be the solution for more complexity. And if you want to leave the "sacred places" 1,6 and 12 untouched, but add 24 to your pip count (2x12), you can place these three stones only on the 8. The now 15 stones also again fit perfectly to the inner logic of the game, as I will show.

The stones are grouped into 2,3 and 5 pieces each. These are the prime numbers among the divisors of 60. 15 stones are played with. This is the sum of the non-trivial divisors of 12! Also, it is the number of rolls that are duplicated among the 36 possible rolls! The 24 squares x the 15 stones per color = 360, the number of degrees of a circle.

What I found most exciting was the question of why we have a total of 167 pips to go at the beginning of the game, no one could ever answer that for me. But with a look at the sexagesimal system, it was suddenly logical: 4500 years ago the 1 was not considered a divisor, because it does not really divide a number. Assuming this, the sum of all divisors of 60 is just 167! And like the 7 (gods of the Sumerians) this number is the sum of all divisors but itself a prime number.

Adding the 1 gives the hours of a week: 168!

In fact, even the Babylonians divided the day into 24 hours.

Now to the etymology of the word "backgammon", because that's where my essay started:

The word abacus originally comes from Greek, and was called "abax". With the Romans it developed to "Abacus" and meant not the Chinese abacus, which many associate, but just the described arithmetic boards, as well as small wax boards, with the same vertical lines. In medieval English, abacus was the name for any kind of calculation board, because these abacus boards were in use well into the late Middle Ages and were only then superseded by abstract written arithmetic.

The word for "game" was "gamen," from the pre-Germanic word "gaman," meaning fun. "Gamen" evolved into "Game" but also into "Gammon".

That backgammon got its name in the English-speaking world is logical, but what has never been part of the discussion is that in the Middle Ages the French ruled over England. William the Conqueror, a Frenchman from Normandy, was king over England in the 11th century, and his sons and other relatives continued this French rule on the island for centuries. This is very exciting because in French the abacus is "abaque" (pronounced like A Bak). The suffix -us of the Latin word abacus has already been lost. It is known that very many words have been assimilated by omitting this very ending.

We also know today that almost 25% of all English words are of French origin, so the French influence was enormous.

Now the optical relationship of the backgammon board with the calculation boards of the Middle Ages is so obvious, that the reference is almost imposing! I therefore come to the conclusion that the game of backgammon got its name while the French ruled over England. Someone must have noticed the similarity, and he or she henceforth called the game "abaque-gammon" (pronounced A Bak-Gammon), an abacus game.

Even under purely English usage, the assimilation of "abacus-gammon" to "a back-gammon" would be logical and explainable, since as I said, the Latin suffix -us often disappeared in everyday usage.

Backgammon is not derived from any other game. Nor was it developed as a calendar. It was as a calculation board, 4500 years ago the first calculating machine of man. It represents the Sexagesimal system of mathematics of the Sumerians. And this mathematics reflects the course of the planets, the sun and the moon.

What I find particularly exciting is the idea that a board originally designed for mathematical purposes had long degenerated into a game of chance until, thanks to great thinkers like Paul Magriel, it became again what it always was:

An abacus, a calculation board!

Alexander Auer, 2021